Europese aandelen: De stille winnaars van de AI-revolutie

Can Big Tech firms sustain their plan to build big and spend big on AI over the next few years? Portfolio Manager Tom O’Hara argues they can, with potential benefits for a range of European companies participating in this multi-year revolution.

11 beknopt artikel

Kernpunten

- With a sustained period of significant capex for hyperscalers ahead, stocks that form part of the ‘AI trade’ are facing a lot of questions about whether or not they can realise their ambitions.

- It is easy to underestimate the hyperscalers’ commitment to underwriting this next technological wave and it is our view that the spending taps will remain open, with sustained benefits for the supply chain.

- The potential ‘Telco-fication’ of hyperscalers warrants close scrutiny. But we maintain conviction in our European ‘picks and shovels’ approach to investing in the beneficiaries of this massive, multi-year capital deployment as a source of macro-resilient revenue growth for suppliers listed in the region.

As with all sizeable market gyrations, the latest dramatic sell-off – this time in stocks considered part of the “AI trade” – required a compelling narrative. Financial media articles are not likely to gain much traction if the main thrust is “something went up or down a lot but for no apparent reason”, even though that is often an accurate explanation (due to the market’s increasing dominance by a combination of short term, computer-driven and passive money).

Conveniently for content creators, there has been an emerging chorus of concern for the vast amounts of capital being deployed by the hyperscalers (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, plus Oracle, Meta and one or two others depending on how you define it) on the build-out of data centre infrastructure to power their AI ambitions. The bout of capex anxiety attached itself nicely to this particular market episode. It is now pretty well known that the budgets are big, at over US$200bn combined per year and growing. Roughly around half of the capital is invested into long-duration assets like land and buildings, with the other half going into shorter-life hardware like GPUs where NVIDIA, as the dominant AI chip designer, would likely be a disproportionate beneficiary.

JHI

JHI

The argument goes that these companies are struggling to demonstrate corresponding AI-related revenues and, as such, they may be forced into a hiatus that could bring the house of cards tumbling down on the AI supply chain. It has managed to gain greater prominence in recent weeks despite the concurrent second-quarter results season bringing both higher capex outlooks and a robust defence from the hyperscalers as to the strategic rationale for their spending splurge. Sundai Pichai (Google-parent, Alphabet’s CEO) summed up the tone succinctly:

“I think the one way I think about it is when we go through a curve like this, the risk of under-investing is dramatically greater than the risk of over-investing for us here.”

Exhibit 1: Capital expenditures by the hyperscalers (2024 onwards based on consensus forecasts)

Note this excludes the substantial investments being made by Meta

Source: Janus Henderson, Bloomberg, Visible Alpha forecast consensus, as at 10 August 2024. Showing total capital expenditure for each calendar year. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

In this article we scrutinise some of the arguments put forward as part of this “AI return on investment (ROI)” scepticism, while offering a few counterpoints of our own. As is common with any model or theory (which is flattering terminology for the unsubstantiated musings of finance professionals, including your writer…), a few tweaks here and there can lead to a very different conclusion.

Big Tech to keep spending for now – the supply chain is positioned to benefit

We think that the bears on AI ROI have underestimated both the hyperscalers’ commitment to underwriting this next technological wave and their willingness to accept an evolution in the financial profile of their businesses. This manifests as an increasing asset intensity (and potentially dilutes returns, but only time will tell) that is evident in financial ratios. Perhaps we are witnessing the metamorphosis of these companies into something closer to telecommunications (Telcom) firms, which for decades have been beholden to large, consecutive capital cycles dictated by technological developments. In this respect, just because the revenue uplift from the capex is not immediately evident, it does not mean the investments will stop. The AI supply chain – to which we are exposed via semiconductor equipment, other data-centre hardware and even construction materials – will, in our view, remain well supported by hyperscaler demand for a number of years.

Is this rational or reckless corporate strategy?

One could make the pessimistic forecast that, far from demonstrating revenue growth sufficient for a respectable return on investment, this enormous capital deployment could prove to be of the ’stay in business’ variety. Even if such a negative AI-revenue scenario were to prevail, we believe it is wrong to assume that the spending taps will be turned off, for the following reasons:

- Self-preservation trumps the kind of superficial economic orthodoxy inherent in the ROI narrative, when the alternative is a non-negligible risk of a shrinking, or even non-existent business within a not-too-distant timeframe. In other words, ‘do or die’. Imagine being the only Cloud Service Provider without AI capabilities, or sufficient capacity, in a world in which AI has successfully proliferated.

- They can more than afford it. Collectively the relevant companies involved in this AI paradigm remain strongly free cash flow-generative and in a growing net cash balance sheet position of hundreds of billions (US dollars), despite major data centre investments. Large-scale infrastructure buildouts have tended to require government backing. Fortunately for the AI supply chain, the hyperscalers are richer and more creditworthy than most governments. This is very different to another contemporaneous technology transition. The diffusion of electric vehicles into society ultimately depends on fickle households to make a judgement on their value, usually with some government-incentives, while also bearing the declining residual value of their vehicles as new, better models enter the market.

- It is not clear who would actually possess the clout to force these behemoths to a halt. It is notable that the most prominent voices of the recent ROI unease do not emanate from the top of the shareholder registers of the hyperscalers. It seems to be more a cohort of media-savvy hedge funds (most of whom probably do not care much beyond a short-term horizon) and Silicon Valley/venture capital practitioners, who one could argue have a deeply ingrained ‘asset light’ mindset (think software), courtesy of the last couple of decades. This leaves them arguably struggling to comprehend the evolution of the hyperscalers’ financial profile into something more asset-heavy, long-duration and potentially cumbersome.

The (wrong) lessons from history

Parallels have been drawn between the AI capex cycle and the investment booms-turned-busts in the railroad and telegraph rollouts of the 19th Century. These were great waves of capital deployment premised on a revenue and profit opportunity that turned out to be overstated.

Even worse for AI by comparison, 19th Century investors at least knew the tangible function – and the route to revenues – of those historic buildouts; freight and people would pay to travel on the railroads; governments, news organisations, the railroads and other businesses, would pay for the speedier transfer of information derived from the telegraph.

But what is the value of AI? If we struggle to even define it, how can we justify the investment? The answer, for now, is the more conceptual and amorphous measure of ‘productivity’, for businesses, for governments, and – maybe – for consumers via smart devices. The argument goes that the “killer” applications are yet to appear. It is perhaps unsettling, but we think the ‘productivity’ prize of AI is so great – and the cost of not securing it such a potential competitive disadvantage – that it is sufficient to underpin the pursuit of it, for now.

Most corporates, at least the big ones we focus on, are expediting their investments into artificial intelligence via enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems that can potentially boost company and systems efficiency, chatbots, enhanced research and development processes, Microsoft Co-pilot and so on. New applications should come through in time. In fact, this article was researched using the AI “chat” functionality within Quartr (which is like Spotify for stock pickers, with live earnings calls and transcripts providing the raw materials for clever AI search and analytics tools).

There is another important distinction that limits the railroad and telegraph analogies: balance sheets. Railroads displaced canals, mostly via newly formed companies. Telegraph displaced letters, flag-waving, couriers and ponies, again mostly via new companies. The microeconomic fundamentals of those investment cycles – the funding position of the investing companies – was therefore more susceptible to boom and bust. AI is better viewed as an iterative technology pursued by already powerful incumbents. Existing profits and cash flows are being partially reinvested into the next generation of functionality. Capital investment is therefore likely to be smoother and less macro-economically sensitive. Consistently high capital expenditure, accompanied by next-generation-technology imperatives, is more akin to the telecommunications sector of the last 30 years or so, than those 19th Century cautionary tales in speculation which were, in effect, exacerbated by speculative business models.

The evidence is building for the potential telco-fication of Big Tech in financial statements

Microsoft offers one of the clearest windows (pun intended) into the rising asset and capex intensity of the hyperscalers: how dependent their revenues are on physical infrastructure. As the most cloud-heavy business mix, Microsoft’s financial statements are not complicated by Google’s search engine and YouTube businesses for example, nor Amazon’s mammoth e-commerce operation.

Between 2014 and 2024, Microsoft has:

- Increased the balance sheet carrying value of property, plant and equipment (PPE) by over 10 times, from c. US$13bn to US$135bn.

- Increased annual capital expenditures by over 800%, from c. US$5.5bn to c. US$44.5bn for the June year-end just reported. Huge amounts of spending now going into buildings and kit every year.

- Increased group sales by nearly 300%, from c. US$87bn to c. US$245bn.

This divergence between Microsoft’s annual investment into fixed assets and its sales growth, means that capex as a percentage of sales has risen from around 6% to 18% and may go higher depending on the future revenue growth it achieves. PPE (or total physical stuff) as a percentage of annual sales has gone from 15% to 55% and is likely to go higher in the medium term, north of 60%, based on Visible Alpha’s aggregation of sell-side analyst forecasts.

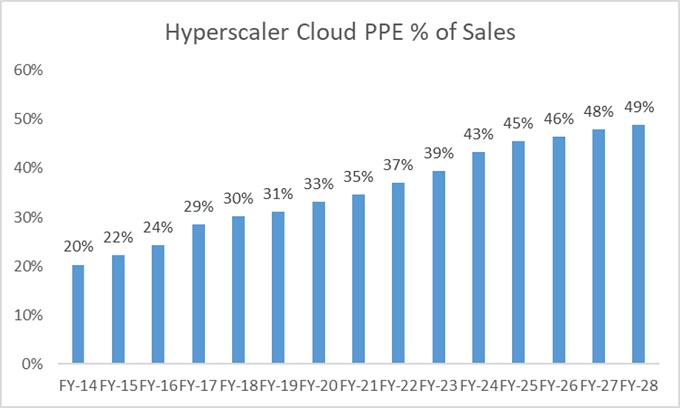

Even more startling is the expected growth in combined PPE for Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Oracle between full-year 2024 (FY24) and FY28: a 75% increase from c. US$550bn to c. US$960bn. That is a lot of money to come down the supply chain in the next few years if they stay the course. As a percentage of overall combined sales for these companies, PPE is expected to grow from the low 40s to close to 50%, though as mentioned, the diversified business interests of Alphabet and Amazon mask the true growth in asset intensity within their cloud businesses.

Exhibit 2: Hyperscaler cloud PPE percentage of sales

Source: Janus Henderson, Bloomberg, Visible Alpha forecast consensus, as at 10 August 2024.

This is where the telecommunications comparison is helpful. If we look close to home, the European Telco sector has consistently deployed capex as a percentage of sales in the teens (and often the mid to upper end), while the likes of Deutsche Telekom, Telefonica, Vodafone and BT all operate with PPE to annual sales of over 70%. These companies share a high dependence on constant investment and upkeep of physical infrastructure in order to generate sales.

This is why we suggest that the potential ‘Telco-fication’ of ‘Big Tech’ is a more useful framework through which to judge the capital investment cycle into AI. At worst, the hyperscalers are on a long-term journey towards the largely pedestrian returns on capital achieved by Telco companies. But that in itself would not threaten the capital deployment from which the supply chain benefits, at least not in the medium term. We expect hyperscalers to still spend big because there is no alternative and because they can afford it. In a positive scenario, AI-related revenues will become very significant once the tangible “killer apps” emerge, allowing the hyperscalers to generate more revenues and attractive returns on capital. If this happens, everyone is happy (including hyperscaler shareholders) and we can retire the Telco analogy. The point is that, whether or not we see a good or bad ROI outcome for hyperscalers, the medium-term capex outlook on which our supply chain investments depend looks well underpinned.

European ‘picks and shovels’ for the hyperscalers

The potential ‘Telco-fication’ of the hyperscalers understandably warrants close scrutiny of those businesses by their own equity owners, but it does not logically follow that this leads to less capex cascading through the supply chain in the near term. In fact, right now it seems to be leading to the opposite because, like a Telco, the last thing you can countenance is lagging your competitors and losing customers. Playing catch up is hard (and expensive); just look at Intel’s woes in the semiconductor industry.

As a result, we maintain conviction in our European ‘picks and shovels’ approach to investing in the beneficiaries of this multi-year and massive capital deployment. Big Tech was for many years an enemy of the European fund manager, who could not invest in this US-centric “only game in town”. Now, the hyperscalers and their rising asset intensity are a friend: a source of macro-resilient revenue growth for the myriad suppliers listed here in Europe.

AI supply chain: The network of companies, technologies and materials involved in the development, and maintenance of AI infrastructure and related businesses.

Balance sheets: A financial statement that summarises a company’s assets, liabilities and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time. Each segment gives investors an idea as to what the company owns and owes, as well as the amount invested by shareholders. It is called a balance sheet because of the accounting equation: assets = liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

Capex (capital expenditure): Money invested to acquire or upgrade fixed assets such as buildings, machinery, equipment or vehicles in order to maintain or improve operations and foster future growth.

Capital investment cycle: The purchasing of fixed assets by a company for the purpose of supporting day-to-day operations.

Carry value: The meaning of ‘carry’ is dependent on the context used. A typical definition would be the benefit or cost of holding an asset, including any interest paid, the cost of financing the investment, and potential gains or losses from currency changes.

Ecommerce: Commercial transactions conducted electronically on the internet.

Enterprise resource planning (ERP): Software that assists with the running of a business, supporting automation and processes in finance, human resources, manufacturing, supply chain, services, procurement, etc.

Financial ratios: Information taken from company financial statements to gain meaningful information about a company.

Free cash flow (FCF): Cash that a company generates after allowing for day-to-day running expenses and capital expenditure. It can then use the cash to make purchases, pay dividends or reduce debt.

GPUs: The graphics processing unit (GPU) in a device that helps to generate graphics, effects, and videos.

Hedge funds: An investment fund that is typically only available to advanced investors, like institutions and individuals with large and valuable assets. These funds can often use complex investment strategies that include the use of leverage (borrowing), derivatives, or alternative asset classes in order to boost returns.

Long duration: A security that is bought with the intention of holding over a long period, in the expectation that it will rise in value.

Macroeconomics (macro)/microeconomics: Macroeconomics is the branch of economics that considers large-scale factors related to the economy, such as inflation, unemployment or productivity. Microeconomics is the study of economics at a much smaller scale, in terms of the behaviour of individuals or companies.

Residual value: The estimated value of an asset at the end of its lease term, or after its useful life has ended.

Return on investment (ROI): A calculation of the total monetary value of an investment, minus its cost.

Venture capital: A type of private equity investing that typically involves investment in earlier-stage businesses that require capital, often before they have begun production or started generating revenues. Deemed a high-risk, high-reward investment it can entail greater risk of capital loss.

Dit zijn de standpunten van de auteur op het moment van publicatie en kunnen verschillen van de standpunten van andere personen/teams bij Janus Henderson Investors. Verwijzingen naar individuele effecten vormen geen aanbeveling om effecten, beleggingsstrategieën of marktsectoren te kopen, verkopen of aan te houden en mogen niet als winstgevend worden beschouwd. Janus Henderson Investors, zijn gelieerde adviseur of zijn medewerkers kunnen een positie hebben in de genoemde effecten.

Resultaten uit het verleden geven geen indicatie over toekomstige rendementen. Alle performancegegevens omvatten inkomsten- en kapitaalwinsten of verliezen maar geen doorlopende kosten en andere fondsuitgaven.

De informatie in dit artikel mag niet worden beschouwd als een beleggingsadvies.

Er is geen garantie dat tendensen uit het verleden zich zullen doorzetten of dat prognoses worden gehaald.

Reclame.

Belangrijke informatie

Lees de volgende belangrijke informatie over fondsen die vermeld worden in dit artikel.

- Aandelen/deelnemingsrechten kunnen snel in waarde dalen en gaan doorgaans gepaard met hogere risico's dan obligaties of geldmarktinstrumenten. Als gevolg daarvan kan de waarde van uw belegging dalen.

- Aandelen van kleine en middelgrote bedrijven kunnen volatieler zijn dan aandelen van grotere bedrijven en kunnen soms moeilijk te waarderen of te verkopen zijn op het gewenste moment en tegen de gewenste prijs, wat het risico op verlies vergroot.

- Als een Fonds een hoge blootstelling heeft aan een bepaald land of een bepaalde geografische regio, loopt het een hoger risico dan een Fonds dat meer gediversifieerd is.

- Het Fonds kan gebruikmaken van derivaten om het risico te verminderen of om de portefeuille efficiënter te beheren. Dit gaat echter gepaard met andere risico's, waaronder met name het risico dat een tegenpartij bij derivaten niet in staat is om haar contractuele verplichtingen na te komen.

- Als het Fonds activa houdt in andere valuta's dan de basisvaluta van het Fonds of als u belegt in een aandelenklasse/klasse van deelnemingsrechten in een andere valuta dan die van het Fonds (tenzij afgedekt of 'hedged'), kan de waarde van uw belegging worden beïnvloed door veranderingen in de wisselkoersen.

- Wanneer het Fonds, of een afgedekte aandelenklasse/klasse van deelnemingsrechten, tracht de wisselkoersschommelingen van een valuta ten opzichte van de basisvaluta te beperken, kan de afdekkingsstrategie zelf een positieve of negatieve impact hebben op de waarde van het Fonds vanwege verschillen in de kortetermijnrentevoeten van de valuta's.

- Effecten in het Fonds kunnen moeilijk te waarderen of te verkopen zijn op het gewenste moment of tegen de gewenste prijs, vooral in extreme marktomstandigheden waarin de prijzen van activa kunnen dalen, wat het risico op beleggingsverliezen verhoogt.

- Het Fonds kan geld verliezen als een tegenpartij met wie het Fonds handelt niet bereid of in staat is om aan zijn verplichtingen te voldoen, of als gevolg van een fout in of vertraging van operationele processen of verzuim van een derde partij.

Specifieke risico's

- Aandelen/deelnemingsrechten kunnen snel in waarde dalen en gaan doorgaans gepaard met hogere risico's dan obligaties of geldmarktinstrumenten. Als gevolg daarvan kan de waarde van uw belegging dalen.

- Aandelen van kleine en middelgrote bedrijven kunnen volatieler zijn dan aandelen van grotere bedrijven en kunnen soms moeilijk te waarderen of te verkopen zijn op het gewenste moment en tegen de gewenste prijs, wat het risico op verlies vergroot.

- Als een Fonds een hoge blootstelling heeft aan een bepaald land of een bepaalde geografische regio, loopt het een hoger risico dan een Fonds dat meer gediversifieerd is.

- Het Fonds kan gebruikmaken van derivaten om het risico te verminderen of om de portefeuille efficiënter te beheren. Dit gaat echter gepaard met andere risico's, waaronder met name het risico dat een tegenpartij bij derivaten niet in staat is om haar contractuele verplichtingen na te komen.

- Als het Fonds activa houdt in andere valuta's dan de basisvaluta van het Fonds of als u belegt in een aandelenklasse/klasse van deelnemingsrechten in een andere valuta dan die van het Fonds (tenzij afgedekt of 'hedged'), kan de waarde van uw belegging worden beïnvloed door veranderingen in de wisselkoersen.

- Wanneer het Fonds, of een afgedekte aandelenklasse/klasse van deelnemingsrechten, tracht de wisselkoersschommelingen van een valuta ten opzichte van de basisvaluta te beperken, kan de afdekkingsstrategie zelf een positieve of negatieve impact hebben op de waarde van het Fonds vanwege verschillen in de kortetermijnrentevoeten van de valuta's.

- Effecten in het Fonds kunnen moeilijk te waarderen of te verkopen zijn op het gewenste moment of tegen de gewenste prijs, vooral in extreme marktomstandigheden waarin de prijzen van activa kunnen dalen, wat het risico op beleggingsverliezen verhoogt.

- Het Fonds kan geld verliezen als een tegenpartij met wie het Fonds handelt niet bereid of in staat is om aan zijn verplichtingen te voldoen, of als gevolg van een fout in of vertraging van operationele processen of verzuim van een derde partij.