Rates to remain high

The cost of capital largely dictates the weather for financial markets and for the companies that rely on them for funding. For much of the past decade, low interest rates have made it cheap for many companies to invest in expansion, but have thinned margins for banks and fixed income funds. The rise in policy rates since 2022 has raised the cost of investment for companies, at a time when they are under pressure to invest heavily in the energy and digital transformations. However, for many of the financial businesses supplying that investment funding – particularly for banks and fixed income funds – higher interest rates raise margins and make their businesses more attractive to investors.

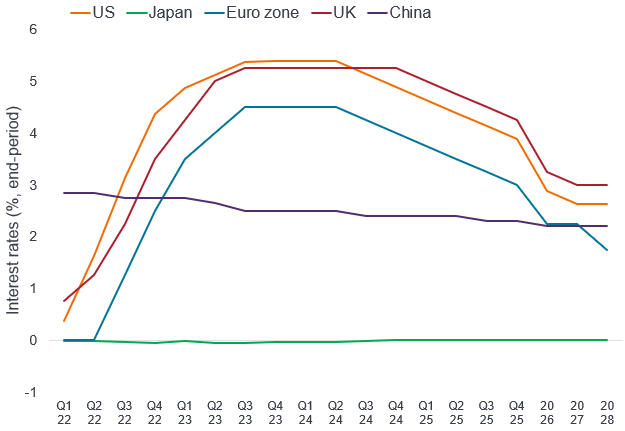

We, at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), expect these trends to persist in 2024. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) are likely to start gradually lowering interest rates from the second half of 2024, but the slow pace of the cuts will soften further as inflation approaches the 2% mark that central banks desire. Markets that followed US policy rates upwards, such as India and Mexico, will follow this downward trend too. Policy rates are already low in China and Japan, and we believe that the cost of capital will remain low in both Asian economies in 2024. Price pressures are likely to remain manageable, and, as a result, the central banks of these countries will look to keep exchange rates attractive in order to boost export competitiveness.

Over the rest of EIU’s five-year forecast period, interest rates will moderate further in Europe and the US, falling to the 2-3% range by 2028, but will remain higher than during the decade of easy money of the 2010s. Fortunately, global growth is forecast to strengthen to 2.7% a year on average in 2025-28, supporting corporate cashflow and supporting continued investment into technology and clean energy. There are substantial risks to this interest-rate forecast, however, given the possible escalation of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, as well as US-China tensions over Taiwan, which could disrupt supply chains and fuel inflation over the forecast period.

Interest rates will start to fall in 2024

Source: Central banks; EIU as at January 2024.

Investors will favour fixed income instruments but avoid certain types of property funds

Higher policy rates have prompted an increase in market interest rates, including those that are applicable for fixed income securities, such as money market instruments, as well as loans and deposits. Asset managers who deal in fixed income securities may potentially benefit from a fillip in returns, bolstered by higher interest rates. This could mark a reversal in the fortunes of bonds and related instruments, shunned by investors during a long period of sluggish, even negative, policy rates. At the end of 2023, investors executed a volte-face, rushing back into money market funds and other instruments that offered positive real returns adjusted for inflation.

We expect a dip in interest rates towards the end of 2024 to support both equities and fixed income securities, helping to maintain or boost valuations further. Lower interest rates will ease the burden on company finances while investors could mop up greater real returns from fixed income securities as inflation declines to comfortable levels. These returns will stabilise in developed countries as inflation and interest rates normalise in 2025-28. However, they are likely to narrow in developing countries, where inflation is likely to remain higher, particularly for food.

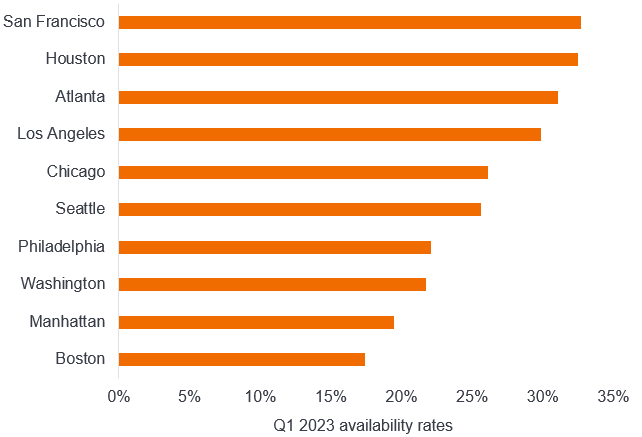

We believe property investments will suffer, however, even more so in China where the sector faces a deep crisis. The future of work is now tilted towards hybrid and some amount of remote work rather than a return to all days in the office, which means that office buildings and centrally located shopping malls have permanently fallen out of favour. Since they are highly leveraged, property companies will likely have to resort to some form of debt restructuring next year. The impact of this indebtedness will feed back to shares of property companies and funds that invest in the sector, making selectivity increasingly important. Funds focusing on warehousing, data centres and infrastructure have the potential, however, to provide appreciably higher returns. Over the longer term, residential development should also support a more general recovery for property investments.

Office availability rates have more than doubled in many US downturns

Source: Savills.

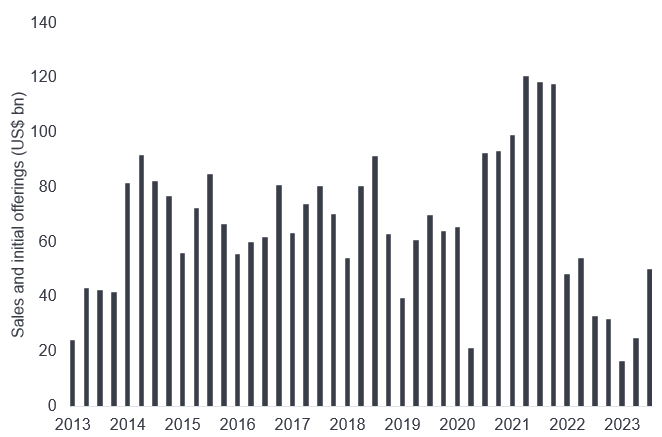

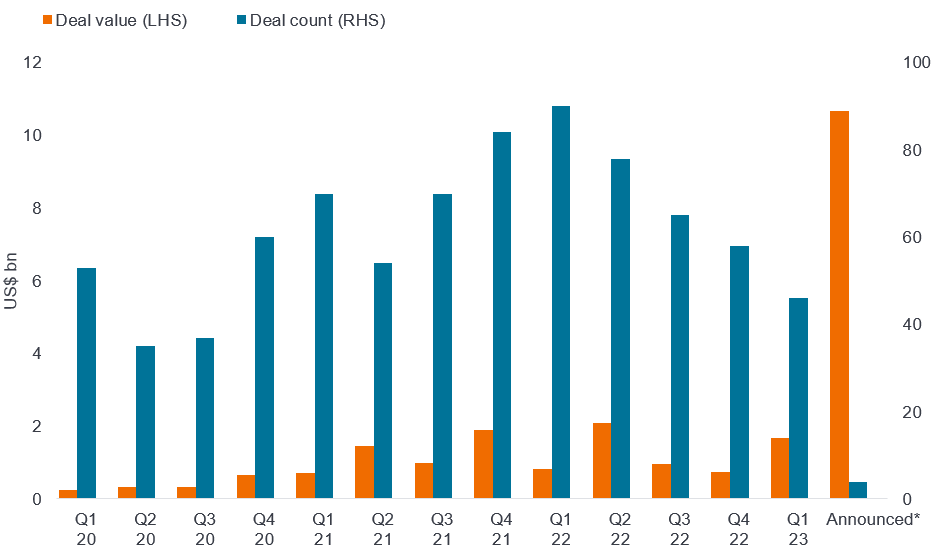

Startups may struggle, private equity will await rate cuts

Steep policy rates have made it harder for startups to raise funds from private investors or via open market listings. With policy rates likely to remain high for at least the first half of 2024, the funding environment will remain difficult for freshly-minted companies in several sectors, including fintech. With highly liquid and safe instruments offering around 5% in markets such as the US, investors are likely to remain markedly risk-averse and selective. New business models are unlikely to attract investors, notwithstanding a recent rush towards artificial intelligence (AI) investments and chipmaker initial public offerings (IPOs), such as the one by ARM, a technology firm headquartered in the UK.

Despite coming off a decade-low, asset sales by private equity firms remain feeble

Source: Bloomberg.

VC deals for generative AI are gaining traction

Source: PitchBook, as at 1 April 2023.

Given these considerations, we believe that the fundraising environment for most startups, including fintech firms, will remain harsh in 2024, with only slow improvements over the following years. As a result, companies will use up the funds built up when policy rates were low as they find new funding hard to come by. IPOs and venture capital-backed companies that do succeed in attracting capital may have to lower their valuations considerably leading to losses for early investors.

Even though most central banks, particularly the ECB and the Fed, have paused rate hikes, buyout managers are being hindered by short-term interest rates of nearly 5.5%. Consequently, debt financing remains an expensive proposition and leveraged buyouts remain few and far between. Private equity players are likely to remain on the sidelines until the second half of 2024, when we believe the first rate cuts will occur. Our hawkish outlook for interest rates over the next five years means that it will be a while before we witness the fundraising heydays during the era of easy money.

Investment will continue to increase regardless

Despite these constraints, we believe that the outlook for corporate and government investment is positive. Our forecasts for foreign direct investment suggest that inflows will rebound in 2024, amid a resurgence in investment into China as well as continued investment into the US, notably in green-tech sectors supported by government incentives. Gross fixed investment will carry on increasing steadily, as countries focus on building out the infrastructure needed for the energy and digital transitions.

There are three main reasons for this sustained investment, which will see money flow in from both governments and corporates. The green and digital transitions are both capital-intensive transformations that are being fully supported by government grants, tax breaks and other tax breaks in many countries, with carbon emissions penalties adding extra impetus. In addition, climate change is likely to increase the depreciation rate of capital, as physical assets will degrade faster with more natural disasters, and money has to be spent on climate-proofing and adaptation. Moreover, the breakdown of relations between China and the US means that more money is being spent on duplication, both for these transformations and for general supply chains.

However, investment risks will remain relatively high, and not just for geopolitical reasons. Many borrowers, whether governments, households or companies, will struggle to shoulder heavier burdens on their borrowing, and may miss repayments or default entirely. Levels of non-performing loans (NPLs) have already ticked up somewhat in most major economies, aside from China, where defaults by property developers have already triggered a crisis. These risks are unlikely to trigger financial crises, particularly in developed countries, but they demonstrate that higher interest rates will remain a double-edged sword.

The return of the cost of capital is one of the three macro drivers that we believe will define the next decade for investors. As the Economist Intelligence Unit notes, this will have a meaningful impact on the investment backdrop and require a proactive approach to security selection. We also know that inflation and higher interest rates are front of mind for our clients – and their clients. In our recent survey of direct investors in the U.S., 67% told us they were very or somewhat concerned about inflation, with 56% worried about higher interest rates. Our role is to apply a disciplined investment approach and share differentiated insights to help navigate change and help position investors for a brighter financial future.”

Ali Dibadj, Chief Executive Officer

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is the process of issuing shares in a private company to the public for the first time.

Leverage is the amount of debt a company has in its mix of debt and equity (its capital structure). A company with more debt than average for its industry is said to be highly leveraged.

A leveraged buyout is the acquisition of another company using a significant amount of borrowed money (debt) to meet the cost of acquisition.

Liquidity is a measure of how easily an asset can be bought or sold in the market. A highly liquid asset is one that can be easily traded in the market in high volumes without causing a major price move.

Non-performing loans (NPLs) are bank loans that are subject to late repayment or are unlikely to be repaid by the borrower.

Safe instruments refer to investments deemed as being ‘risk-free’, such as government bonds.

A venture capital-backed company is a start-up or small business, typically believed to have high growth potential, which is financially supported by a private equity firm in exchange for an equity stake.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.