In summer 2023, the market honed in on how the UK was becoming an outlier on the inflation front, with prices and wage growth proving more stubborn. Since then, while there has been some progress, the UK continues to have the highest core inflation among major developed markets. Bond investors have been unimpressed: in 2024, UK government bonds (gilts) were the worst performing government bonds of the leading developed market countries as their yields rose and prices fell.1

There have been much better opportunities for global bond investors in other countries, such as Europe where growth and inflation have decelerated and the European Central Bank picked up the pace of rate cuts, or Canada, where rising unemployment and low inflation encouraged the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates aggressively.

It is now three years since the big post-COVID inflation shocks and as the dust settles, the UK bond landscape remains the most challenging in the developed world. The reasons are the chronic issues that have been lingering for several years and which the October 2024 Budget exacerbated, top of which is sticky inflation. Meanwhile, the combination of high interest rates and weak economic growth is driving fiscal sustainability concerns.

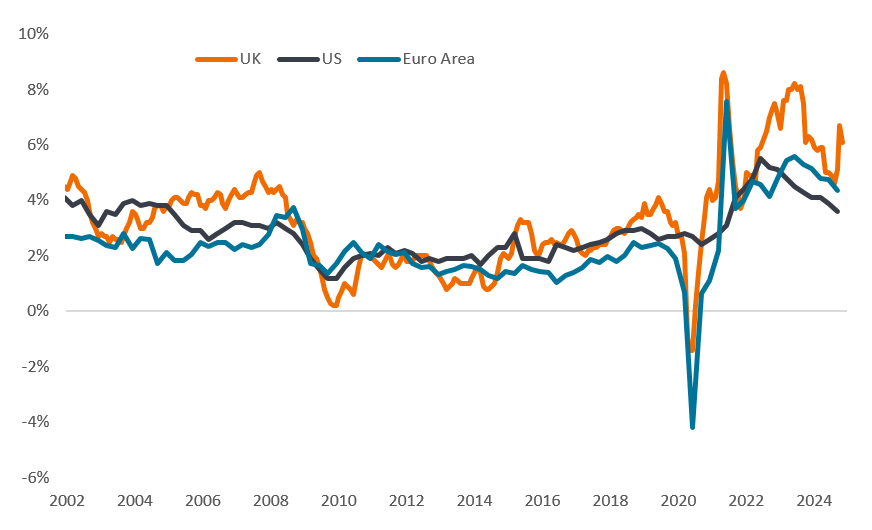

While the UK consumer prices index (CPI) inflation reading for the 12 months to December 2024 came in slightly lower than expected (2.5%, with core inflation at 3.2%) this may be a temporary reprieve.2 A big drop in airfares is expected to reverse, energy prices have risen again, and the economy may have to navigate a new inflation uptick as businesses seek to pass on some of the tax costs that were loaded onto them in the Budget. Even UK households are not convinced that inflation is beaten, with them reporting a rise in inflation expectations for the coming year from 3.3% in October to 3.7% in December.3 Added to that, in April, a higher UK minimum wage takes effect, with increases substantially above the rate of inflation. While undoubtedly welcomed by younger and lower-paid workers, the upward ripple effects may well keep wage growth elevated relative to other developed markets (see chart).

Wage growth (year-on-year % change)

Source: Bloomberg, private sector wage growth, January 2002 to December 2024.

Taken together, markets have become concerned that weak economic growth and stubborn inflation could put additional stress on UK government borrowing levels. Britain therefore finds itself between a rock and a hard place. Its economic growth shares more in common with the moribund growth of the Eurozone, yet worries about inflation and government borrowing levels mean investors are currently demanding high yields to lend to the UK government. In turn, this squeezes the headroom on spending available to the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

This is unlike autumn 2022 and the Liz Truss government mini-Budget debacle where a spike up in gilt yields was quickly remedied by the Bank of England stepping in and buying bonds to halt a deleveraging spiral. Instead, longer term healing is required for the UK to address some of its chronic challenges.

Is there hope? As bond investors, we are prone to look for risks, but sentiment towards UK bonds could improve if there was sustained progress on bringing down core inflation. This would make the Bank of England more amenable to larger rate cuts given the weak growth backdrop.

US corporate outlook remains supported

We remain constructive about corporate bonds and other forms of credit, particularly in the US. There, high government bond yields are reflective of a buoyant economy. The US economy is proving adept at motoring along, with ongoing job creation and strong aggregate earnings growth among companies.

Credit spreads (the additional yield a corporate bond pays over a government bond of similar maturity) are low historically. While this leaves little cushion if the economy were to take a turn for the worse, it is reflective of market confidence in the outlook for companies. Earnings growth remains strong and most companies have avoided taking on excessive debt.

Corporate bond yields are attractive in our view – buoyed in part by the high yields on government bonds – and are reminiscent of the pre-Global Financial Crisis period (2002-2007) when markets delivered an average annual return of 5.8% for US investment grade bonds and 8.5% for US high yield bonds, although there is no saying that history will repeat itself.4 In early January 2025, US investment grade yields averaged 5.5% and yields on high yield bonds averaged 7.5%, which are favourable compared to cash yields of around 4.2%.5 This differential is maintaining strong demand for corporate bonds.

As the market prepares for earnings season and anticipates President Trump’s tariff and trade plans in the first quarter of 2025, we are adopting a conservative approach. We continue to adhere to our ‘sensible income’ philosophy, focusing on companies where we have a high degree of confidence that they can meet their payments to bondholders and which operate in sectors with more reliable cash flows. Given the political and economic uncertainty prevailing in the market we expect to be nimble, using any sell-offs to add bonds we like and selectively participating in bonds that are newly issued to the market.

1Source: LSEG Datastream, total return in local currency of 10-year government bonds in UK, US, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Canada.

2Source: Office for National Statistics, UK Consumer Prices Index, Core CPI = CPI excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco. Data to 31 December 2024.

3Source: Citi/YouGov survey of British households’ expectation for inflation in a year’s time, December 2024.

4Source: LSEG Datastream, ICE BofA US Corporate Index (investment grade), ICE BofA US High Yield Index, date to date, annualised total returns in US dollar, 31 January 2001 to 31 January 2007. Past performance does not predict future returns.

5Source: LSEG Datastream, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, USD Cash Deposit overnight rate, yield to worst, at 10 January 2025. Yield to worst is the lowest yield a bond (index) can achieve provided the issuer does not default; it takes into account special features such as call options (that give issuers the right to call back, or redeem, a bond at a specified date). Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Corporate bonds: Bonds issued by companies. These can be rated investment grade by credit rating agencies, which means they are perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting (failing to meet repayments to bondholders. Conversely, bonds rated high yield carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

Deleveraging spiral: Situation where pension schemes were forced to sell gilts to raise cash to meet collateral demands at hedge funds they had invested in. This caused gilt prices to fall and their yields to rise, exacerbating the problem.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. Core inflation excludes volatile items such as food and energy.

Yield: The level of income on a bond over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate.