High growth, high inflation?

Trump’s pro-growth agenda is expected to increase pressure on the US Federal Reserve in its delicate balancing act of maintaining stable prices and a healthy labour market. However, as noted by Chairman Jerome Powell, this is unlikely to significantly impact Fed policy decisions. We believe it is more likely to lead to a more hawkish Fed – all things equal – to preserve its credibility to tackle inflation and given higher inflation expectations under the new administration.

Many of Trump’s proposed policies are expected to be inflationary, such as trade tariffs, higher fiscal spending (such as defence) and tax cuts. His pro-growth policies and a loosening fiscal policy stance could also create a tailwind for US growth, attracting capital into the US and boosting the dollar. On the other hand, if investors start worrying about the ballooning US fiscal deficit, this could have the opposite effect on the dollar. A strong greenback could pressure EM currencies and ergo local currency EM bonds. However, it is likely EM central banks will tread cautiously in their policy responses, as weaker currencies add to inflationary pressures. Altogether, this is likely to drive less optimistic growth than previously expected in EM.

Capital flows to EM postponed?

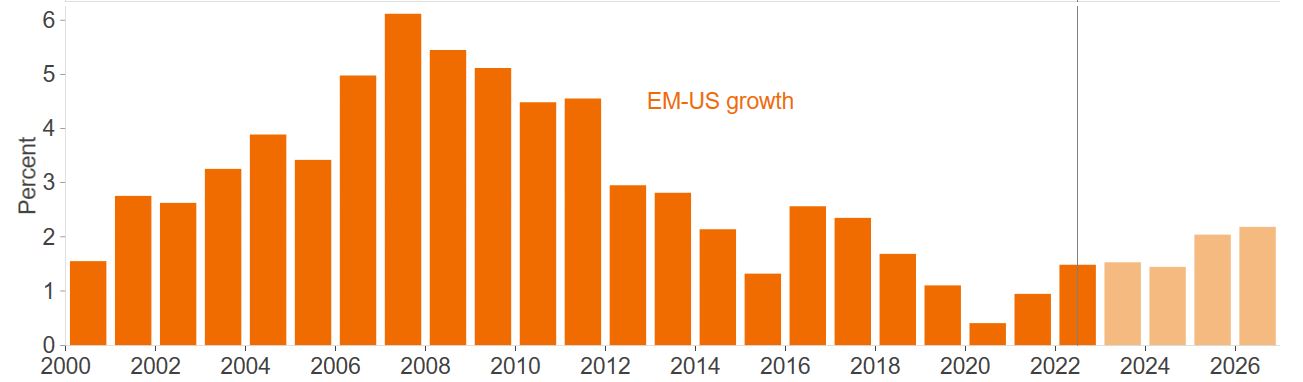

Depending on the eventual US firepower to boost growth, we still expect the EM-US growth differential to trend higher (according to IMF growth forecasts shown in Figure 1), albeit less than before. This could weigh on the prospects of capital flows to EM in the short term.

Figure 1: EM-US growth differential still expected to widen over medium term but less so in 2025 now

Source: International Monetary Fund, Macrobond, October 2024. Light shaded tangerine represents a forecast. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

However, looking at flows outside of EM dedicated funds, some argue1 that local EM investors are stepping into emerging markets debt hard currency (EMD HC), which could mean a new and potentially stickier source of financing. Moreover, if pro-US growth policies are initiated ahead of tariffs, this could help to support credit spreads generally, including in EM. Economic growth is a priority for the US and tariffs could weigh on growth and so it would make sense for fiscal policy, such as tax cuts, to be prioritised first and tariffs later. Indeed, in the first Trump presidency, tariffs came later in his term.

We believe US policy uncertainty is likely to remain elevated, and this could result in periods of spread volatility as markets digest the outcomes. It is also worth remembering that during Trump’s first term, after the initial repricing in late 2016, EMD HC spreads tightened throughout 2017 as the “risk-on” sentiment in US financial markets filters through into credit spreads globally.

Another factor to consider in influencing credit spreads is rising US Treasury yields and an increase in the term premium. According to Morgan Stanley research, historically any move in US Treasury yields of more than 50 basis points – primarily driven by real yields – sees EM credit spreads widen as they can no longer absorb any further moves in UST yields2. However, credit spreads and the underlying Treasury yields are negatively correlated, stabilising total returns during positive and negative markets. In a risk-off environment, the underlying Treasury yield becomes a buffer, limiting a total return loss and vice versa in risk-on markets. The exception to this rule of thumb is when inflation is behind the rise in risk aversion. So much depends on whether a rise in the US Treasury yield is fuelled by higher inflation expectations or other factors. In our view, credit spreads are affected more by the speed of a rise higher in real yields rather than the magnitude.

Trade tariffs and tax cuts

Trump’s proclaimed priority has been to bring manufacturing back to the US through tariffs and tax cuts. However, it remains unclear what will transpire as actual outcomes (rather than political posturing) and what can be implemented from a practical perspective, considering the risk of retaliatory action. After all, in Trump’s first term, trade was a bargaining tool. Some measures will require Congressional approval. One example of this is the removal of countries’ PNTR (permanent normal trade relations) status, a legal designation in the United States for free trade with a foreign nation. A Republican clean sweep facilitates this process. Another is Trump’s proposal to reduce the corporate tax rate from 21% to 15% for US domestic producers.

Trump has pledged 60% tariffs on exports from China to the US and universal tariffs of up to 20% on all other countries’ exports to the US. There will be relative winners and losers if this comes to fruition. To categorise these, we believe two key dimensions are trade and funding costs, as well as targeted tariffs. China and Mexico (as the country with the largest US exports as a percentage of GDP and in the context of a wider renegotiation of the US Mexico Canada Agreement or USMCA) are likely to see the most impact, while smaller open economies – such as Vietnam and Singapore – may also be affected, depending on their trade export volume to the US (Figure 2). However, some of these countries are not represented in the EMD HC universe. Emerging Asia has nearly twice the US export trade exposure (as a percentage of GDP) as any other region and the largest US dollar net trade surpluses with the US3.

Figure 2: Top 20 countries with most exposure to US exports as a percentage of their GDP

Source: Janus Henderson, IMF, 12 November 2024. Tangerine countries are in the EMD HC universe, as represented by the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified index.

Given imported inflation, those countries with high imports in their trade balance, as well as running a large trade deficit, would be most vulnerable to weakness in their currencies. Tighter immigration controls could also influence those countries where tax remittances from the US form a part of their GDP, such as those in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The impact from tariffs, however, is likely to be somewhat mitigated by currencies adjusting, buffering some of the direct impact, and trade will reorient as a buffer too. A disinflationary effect could therefore emerge elsewhere, such as in Asia, as China looks to avoid punitive costs by diverting its exports to alternative EM countries. This could create monetary tension in Asia, with central banks possibly needing to cut rates amid declining exports and inflation, despite a strong US dollar. Currency weakness could, however, create caution in moving the needle on monetary policy too much, as mentioned earlier. When considering the impact on individual countries, investors need to be cognisant of the starting point and the fiscal or monetary room to counteract effects from the US.

The negative growth implications from tariffs and immigration policy could also somewhat offset inflation risks. Moreover, tariffs are often considered to be inflationary only in the short term, as consumers adjust their behaviour to higher prices and growth slows. The second-order effects need to be considered.

China – fiscal thrust?

A key target in the tariff action and one that is struggling with its own economic woes is China. It just announced (seemingly timed after the US election result) a US$1.4tn package to support local governments in their fiscal troubles and free up spending capacity, but the package undershot market expectations. The National People’s Congress (NPC) press conference did not reveal more details on other priorities, such as supporting consumption, stabilising the housing market and boosting bank lending through helping banks to recapitalise through central government bond issuance. However, China could be saving its firepower to respond to the eventual Trump policies, perhaps before the Chinese New Year and post Trump’s inauguration. Assuming the 60% tariff hike on China were to materialise in the first half of next year, JP Morgan estimates that this could trim 1 or 2% off China’s real GDP growth depending on China’s policy response4.

Differentiated response across EM

The combination of higher US rates (for longer) and weaker EM growth under a Trump presidency could negatively impact highly indebted countries that face high funding costs. As discussed, a strong dollar tends to weaken EM currencies, which adds pressure on imported inflation and limits the room for monetary easing or conversely, adds to tightening in EMs.

On the flip side, some EM countries have entered funding agreements with multi-lateral agencies such as the IMF which encourage fiscal sustainability. According to our analysis using IMF data, 42% of the countries in the JPM EMBI GD Index are in IMF programmes5. Market access and funding has improved significantly for BB-rated and B-rated countries, while significant progress has been made in restructuring cases. The direct effects of Trump 2.0 on many of these smaller countries in the universe will be small, in contrast to some of the larger markets such as Mexico and China.

Countries with a high dependency on trade with the US are also vulnerable to Trump 2.0 impacts, as well as those operating in industries where the US could ramp up domestic production. Enhanced domestic oil production in the US could adversely affect oil-exporting countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). However, the overall inflationary impact is nuanced. For example, lower commodity prices from more oil production as well as a potential solution to the war in Ukraine (a ceasefire has been speculated) could lead to more food production and lower food prices over time.

Climate energy policy is another area to watch, as ongoing green transitions may be hindered alongside loosening of regulation on US oil and gas exploration and production. A carbon border tax and tariffs on the imports of renewable energy components – such as those supplied by countries in Asia – are also a potential, as well as less support for debt-to-nature swaps. These aim to refinance a country’s debt at lower relative interest rates, in return for a commitment to spend a portion of these savings on nature conservation.

It’s all about alpha

Pervasive policy uncertainty is likely to be reflected through credit risk premia alongside potential volatility in sovereign credit spreads in EMD HC, but we do not believe this materially alters the fundamental picture for the EMD HC universe. EM sovereign credit ratings continue to outpace downgrades6. While there will be relative winners and losers, the eventual impact won’t be the same across the heterogeneous EM universe. Differentiated responses are likely to arise across EMs given countries’ specific monetary, inflation and fiscal position, as well as trade dynamics with the US. This could lead to mispriced opportunities emerge as the reality unfolds and as active investors, we aim to capture alpha through these and tap into the long-term potential of emerging markets.

Alongside careful country selection, given the rates risk, duration is also another aspect to consider in portfolio construction. We continue to favour shorter-maturity high yield issuers vis-à-vis more rates-sensitive longer-dated investment grade issuers. The latter will be more sensitive to swings in Treasury yields (higher duration), and the tighter level of investment grade sovereign spreads means there is less of a buffer against any spread weakness.

Footnotes

1 Source: JP Morgan on official data, BIS and anecdotal evidence, 22 October 2024.

2 Source: Morgan Stanley, 3 September 2024.

3 Source: UN, IMF, Haver Analytics, Morgan Stanley Research, 3 September 2024.

4 Source, JP Morgan, 8 November 2024.

5 Source: Janus Henderson estimates using IMF data, as at 31 July 2024. Countries are those in the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index.

6 Source: Bloomberg, 31 October 2024.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Credit Spread is the difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment.

10-Year Treasury Yield is the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bonds that will mature 10 years from the date of purchase.

Alpha compares risk-adjusted performance relative to an index. Positive alpha means outperformance on a risk-adjusted basis.

The JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD) tracks liquid, US Dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities.