As economies around the globe grapple with higher inflation created by Russia’s war in Ukraine and persisting supply chain issues, focus has turned to the US as a beacon in the storm. Although slowing somewhat, its economy is proving stronger than oak in the face of stubbornly high inflation, with recent jobs data showing unemployment falling to 3.5%, the lowest level since 1969.1 A resilient economy has fortified the Fed’s resolve to curb inflation through aggressive interest rates hikes, which in turn has strengthened the US dollar (USD).

The combination of a stable economy compared to global peers coupled with higher interest rates has also resulted in the USD being the safe-haven asset of choice in the current market environment. Year-to-date, the USD has strengthened around 10% against a basket of major currencies.2 Some investors are worried about the impact this might have. In the past, a strong dollar has created financial and economic stress, especially for Asian Emerging economies – raising concerns whether this may be reminiscent of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997.

Mike Kerley and Sat Duhra, Portfolio Managers of Henderson Far East Income, believe that the conditions today are much different. The finances of Asia’s economies are much more robust, and businesses are more conservatively managed with lessons learned from the folly of the past. Here, we look at the evolution.

What happened in 1997

In early 1997, then Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan began a series of interest rate hikes as a pre-emptive strike against what he saw as inflationary pressures coming down the road from America’s overheating economy. As is the case today, the resulting interest rates rises encouraged money to flow into the US, significantly strengthening the dollar.

At the time, many of Asia’s currencies were pegged to the dollar. At first, the strong dollar pummelled the Thai Baht. As Thailand did not have sufficient capital reserves to keep it propped up, the currency was forced to be floated, and its subsequent devaluation in the FX markets was severe.

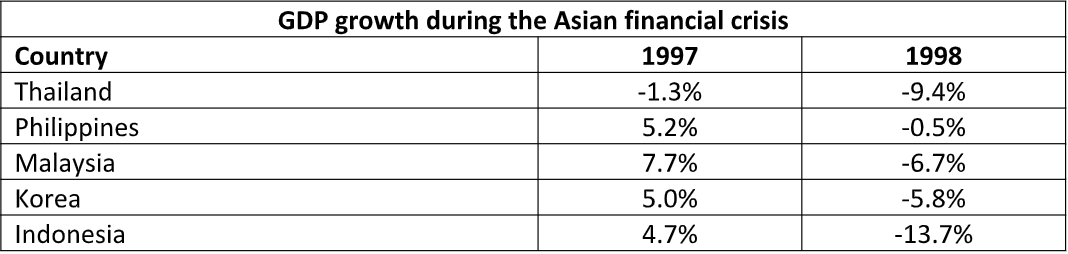

The impact caused a knock-on to other Asian currencies including in Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Korea, and so on, forcing governments to spend billions defending them. When contagion finally reached Hong Kong and it attempted a similar defence, its stock market, then a large constituent of Asian financial markets, dropped 10% in a single day.3

Source: International Monetary Fund – The Asia Crisis: Causes, Policy Responses, and Outcomes, October 1999

By later that year, volatility in Asia’s stock markets had spread around the world. Across East Asia, weaknesses in the currency had spread into property and equity markets, and the crisis evolved into full-blown political and financial nightmare as capital reversed flow and economic growth began to sharply decline. In late 1997 and 1998, Indonesia, Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand experienced net capital outflows of about $80 billion, plunging them from “growth miracles” status into the worst recession they had seen in decades.4

So, how did it happen?

At the time, international money was cheap and the rates of return in Asia high. It made for the perfect arbitrage: money could be borrowed cheaply in international markets and invested for high returns in Asia. It meant that many Asian countries became very reliant on inward investment and built large deficits.

In addition, companies, and banks, which were enjoying loose regulatory oversight, borrowed lots of US dollar-denominated debt in the credit markets, often with very short maturities. As is often the case when too much money is sloshing around, it wasn’t invested particularly wisely either.

When the currencies started weakening, it left the companies exposed the ravages of foreign exchange rate moves. Nothing could be done to resist currency devaluations given how meagre the FX reserves use to prop-up domestic currencies were – a consequence of fiscal mismanagement. The spiralling cost of the servicing their debt left companies and banks in severe hardship, and many became insolvent.

Changing times

The aid received from institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forced some fiscal soul-searching amongst Asia’s governments and central banks, and hard lessons were learnt over the perils of bingeing on foreign debt. Most Asian nations now run surpluses and have large foreign currency reserves. Banks are more strictly supervised and have much-improved risk management. Exchange rates are more flexible and foreign exchange buffers are sufficient to withstand capital outflows and smooth over market volatility.

Take Indonesia, one of the worst-affected countries in 1997/8. Following the crisis, Jakarta introduced a cap of 3% of GDP on the size of the deficit in any one year. With almost $130 billion remaining in foreign currency reserves, Indonesia’s public finances are also in a sound position to continue defending the currency.5

For companies, the memories of the crisis remain visceral for management who experienced it or whose parents did and lost everything. Financial management has improved: balance sheets and cashflow are much stronger. Levels of unhedged, short-term foreign debt is significantly lower, with loans tending to be made in domestic currencies. Combined with high profitability and high economic growth in the years to come, it means the dividend growth story has become an intriguing one for investors.

Prospects in the region

The structural reforms implemented over the years have put Asian economies and companies in good stead to deal with an uncertain and volatile market environment. Asia is the growth engine of the world – over the past 10 years, profits at its companies have grown 149% versus 101% for the rest of the world.6 It is hugely diverse with hundreds of strong dividend-paying companies to choose from. Given they tend to be under-researched relative to other stock markets, it presents hidden gems for actively managed trusts such as Henderson Far East Income to find.

What is more, Covid impacted the region far less than others, and profits have continued growing strongly since. Given the current state of affairs across the rest of the globe, this stability is particularly attractive. Of course, profits are the basis of dividends, and Asia’s dividends are up 139% over the past decade, versus 109% for the rest of the world. In 2022/23, dividends in Asia are expected to rise by 6% and 8%, respectfully, to a total of £333 billion, a new record.3

And yet, companies still remain quite conservative in their fiscal management, with pay-out ratios over the past 5 years – the percentage of net income paid in dividends – averaging 39% versus 47% for the rest of the world.3 It points to plenty of wiggle-room to grow.

Asian companies are increasingly becoming household names around the globe. As cashflows continue increasing and dividend growth remains stronger than the wider world, the Asia Pacific region, 25 years on from its terrible financial crisis, has got to be one of the most attractive dividend stories there is for income seeking investors. If you’re looking to potentially diversify your portfolio’s income, look to Henderson Far East Income.

1Source: US Jobs Rise While Unemployment Drops, Keeping Pressure on Fed – Bloomberg

2Source: Bloomberg as at 15/11/2022

3Source: Hong Kong Stock Crisis Sets World Markets Tumbling – Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

4Source: Asian crisis post-mortem: where did the money go and did the United States benefit? (bis.org)

5Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/indonesia/foreign-exchange-reserves

6Source: Henderson+Far+East+Income+Limited+-+2022+Report.pdf (janushenderson.com)

Capital outflow – Capital outflow is the movement of assets out of a country. Capital outflow is considered undesirable as it is often the result of political or economic instability. The flight of assets occurs when foreign and domestic investors sell off their holdings in a particular country because of perceived weakness in the nation’s economy and the belief that better opportunities exist abroad.

Current account surplus – Current account surpluses refer to positive current account balances, meaning that a country has more exports than imports of goods and services.

FX – Foreign exchange (Forex or FX) is the conversion of one currency into another at a specific rate known as the foreign exchange rate. The conversion rates for almost all currencies are constantly floating as they are driven by the market forces of supply and demand.