For portfolio managers and investors alike, the experiences of 2020 will prove difficult to erase from the memory. As we reflect upon the extraordinary – for once, the word is entirely apposite – developments of the year, one facet in particular leaps immediately to the forefront of our collective consciousness: dividends … or rather, their reliability.

Whilst markets across the globe have suffered substantially at the hands of the COVID-19 pandemic, those seeking income have been especially hard hit. Traditionally, and for as long as most of us can remember, the ready solution to fulfilling the requirement of low-risk, secure income was a portfolio of high-quality bonds, both sovereign and corporate. A portfolio of that construction could largely be relied upon to provide a ‘natural’ income from interest receipts on par with, or ideally exceeding, inflation. No longer.

Interest rates are on the floor. In March 2009, the Bank of England cut the UK base rate to 0.5%, the lowest level since the institution was founded in 1694, cutting it again to 0.25% after the EU referendum. Though the rate was raised in 2017 and 2018, the bank cut the rate twice in March 2020; first from 0.75% to 0.25% and then further to its current record low level of 0.1% – on the justifiable presumption that the pandemic would precipitate a “sharp and large” economic shock. Admittedly, inflation has also fallen in recent years, but not to the extent that it has offset the interest rate decline. Predictably, bond yields have experienced a parallel collapse, also to historic lows. Investors understandably alarmed by the coronavirus have sought refuge in paying higher prices for declining yields and, as a consequence, many assets with attractive income have been bid unsustainably, simply through yield demand. In December, Bloomberg confirmed that the total outstanding value of negative-yielding bonds had swelled to a record $18 trillion globally, representing 27% of the world’s investment grade debt.1 However, six months into 2021, bonds yields have recovered meaningfully as positive developments in the global rollout of COVID-19 vaccinations and expectations for large US stimulus have lifted global growth expectations.

The unique challenges of the current investment climate have stimulated a considerable degree of novel thinking and, unsurprisingly, investors – seeing their traditional sources of income, such as bonds and cash deposits, enervated – have pursued viable alternatives in the equity markets. Whilst equity income has undoubtedly come into its own, COVID-19 has itself sparked an analogous epidemic however, with recent widespread corporate dividend-cutting and suspensions, and dividend decisions heavily influenced by non-financial considerations, serving only to exacerbate an already taxing environment.

The importance of dividends

The seasoned investor will need little reminding that the chief appeal of corporate equity is that it can deliver two valuable elements of return: capital and income. The two are often conflated however, a commonplace error prompted by the reality that income stability is masked by capital volatility. Consider the UK market, as represented by its two key indices: the FTSE All-Share and FTSE 100. In the 30 discrete years since 1991, both indices returned a capital gain in 20 of those years, whereas they – needless to say – delivered a positive income return in 100% of the years.2 Despite not being a terribly profound observation, it does compel one to examine the question of dividend returns discretely, and in more depth.

On New Year’s Eve 1999, at the height of the ‘dotcom’ boom, the FTSE 100 stood at a peak of 6,930. One would have been astonishingly prescient to have suggested that, 21 years later, the index would be lower. And yet it was: at the close of 2020, the FTSE 100 hovered 7% lower around 6,460 albeit in unprecedented circumstances, having reached its all-time peak in mid-January. When looked at in isolation, indices paint a less than accurate picture of performance however, in that, by ignoring the effect of income, the view they present is one-dimensional. For greater clarity, one needs to look at the total return, of which a fundamental component is dividends. Total return is a straightforward measure of the composite return from an investment – for shares, it comprises the combination of capital gains through increases in the share price with income gains through dividend payouts but, importantly, it assumes that those dividends are reinvested as they are received.

It remains something of an oddity that total return indices are not more widely publicised, given that they offer a more holistic – and therefore more reliable – measure of overall investment returns. It should come as no surprise that, on reviewing the performance of the FTSE 100 on a total return basis over the same 21-year period, the picture looks markedly different. Between 31st December 1999 and the same date in 2020 – a span of time which encompasses three bear markets – the index experienced a 97% return. That equates to an average annual return of roughly 3.3% – not overly impressive, but, unlike deposit investments, you would still have beaten inflation … and it’s certainly rather more comforting than a circa 7% loss. Clearly, it’s the reinvestment of dividends that has come to the rescue and illustrates the beneficial effects of compounding … or what Einstein called the “eighth wonder of the world”.

The appeal of dividends, and therefore dividend payers, takes a number of forms.

- First, they are paid in hard cash and, as such, are a matter of fact not conjecture. In short, companies that regularly pay dividends are less likely to be indulging in what has come to be known as ‘creative accounting’. Management teams, particularly those under short-term market pressures, can be adroit at making earnings look good but, with a (usually) twice-yearly dividend obligation to meet, conjuring tricks of that kind become rather more problematic because they show up as an increase in debt. Moreover, dividends are explicit, very transparent public promises – breaking a promise of that kind is embarrassing to management, damaging to share prices and typically seen as an admission of failure.

- Second, the payment of dividends, in and of itself, represents a powerful way for a business to promote its financial well-being and to send a potent message about its view of the future prospects. A willingness – coupled with a demonstrable ability – to maintain and grow dividends over time provides vital evidence of sound fundamentals, robust business plans, and an abiding commitment to shareholder value.

- Third, companies with a solid track record of dividend payment are likely to have more predictable earnings and cash flows. Dividends can therefore serve as a useful metric when looking to identify well-run, profitable businesses that are both focused and efficient in their deployment of capital, and therefore likely to flourish. Before corporations were legally obliged in the 1930s to disclose key aspects of their financial status, an ability to pay dividends was one of the few manifest signs of health, and remains a decidedly persuasive indicator today.

- Finally, dividends can fulfil a critical role as a ‘bear market protector’ or ‘return enhancer’ when markets are in decline, or when they are stagnant because valuations are elevated, and the upside potential is limited. This has been the case on numerous occasions, and often for quite lengthy periods: the Nasdaq Composite Index didn’t gain a single point for almost the first 14 years of this century, for example.3

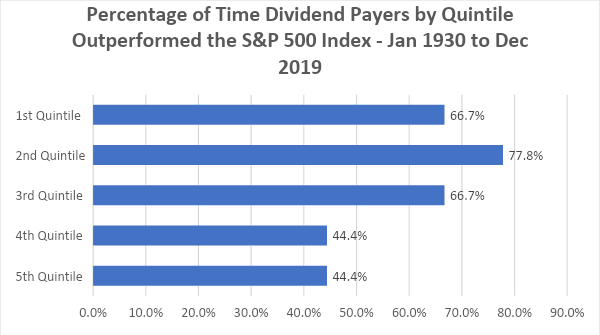

Do dividend payers outperform?

As with all the best tales, there is a twist, however. As can be seen, the best performance was achieved by those companies paying high, but not the very highest, dividends. Whilst this may at first sight appear counter-intuitive, given that the ability to pay a generous dividend is regarded as a reliable indicator of financial health, a likely explanation is that the first quintile’s very high dividend pay-outs may not always have been sustainable. It’s an important finding, and one which provides a convenient segue to the circumstances in which we now find ourselves, given the widespread recent popularity of dividends and the implications of severely suppressed corporate earnings.

One of the key differences of Lowland’s investment approach versus its UK income peers has always been its multi-cap remit, with investments spanning from larger companies listed on the FTSE 100 down to smaller companies listed on the FTSE AIM All Share Index (AIM). This approach allows James and Laura to expand their investible universe materially; as at August 2020 the number of stocks with a trailing 12-month dividend yield of more than 2.5% in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 combined was only 122. However, by extending the universe to include the FTSE Small-Cap and AIM indices the number of stocks became 273, increasing the investible universe by over 2x. The sector and geographic composition of companies also differs as they become smaller. Typically, smaller companies are more domestic in their exposure (companies often focus on their domestic market initially before expanding overseas), and more cyclical (companies in more defensive industries such as utilities and pharmaceuticals are typically larger). Therefore, by investing across all sizes of British business, James and Laura are not only giving themselves greater choice in their stock selection, they are also gaining diversification from exposure to a broader range of industries.

Multi-cap investing typically brings with it a greater exposure to the domestic economy. Lowland is no exception to this, with 53% of portfolio sales exposed to the UK as at the end of April 2021 compared to 26% in the FTSE All-Share benchmark. While this was a headwind to performance of the Trust following the EU referendum in 2016, driven by (for example) currency headwinds as a result of weaker Sterling – the recent clarification surrounding Brexit, combined with the UK’s successful vaccination rollout and surplus of consumer savings following the pandemic, could mean that these headwinds are now set to reverse. This comes at a time when UK equities continue to trade at a valuation discount relative to overseas peers, leaving them vulnerable to private equity approaches. This private equity interest has been evidenced across the breadth of the UK market in recent months, including within Lowland’s portfolio where there have been two recent bids (property owner and developer St Modwen, and aerospace components suppler Senior). James and Laura see this private equity activity as demonstrative of growing confidence in the UK economic recovery as well as the attractive valuation opportunities available.

The portfolio is split into three regions, North America, Europe and Asia Pacific, with none representing more than 50% of assets. No stock is over 5% of the portfolio. Its current yield of 3.7% pa10, coupled with the fact that dividends are paid quarterly (in February, May, August and November), makes it an attractive option for the income-seeking investor. Indeed, the trust has established a track record of rising income delivery. Since launch:

- the dividend has grown from 1p per quarter to 1.50p per quarter11

- dividends have grown every financial year at a greater rate than inflation11

- the capital value has grown from 100p to 168p12.

Whilst dividend cuts were clearly a headline phenomenon in 2020, the impact varied significantly across both regions and sectors. The weakest results came from the UK, Europe and Australia, Japan remains somewhere in the middle, while emerging markets (thanks in large part to China), Canada and the US have fared better. The benefits of the trust’s international diversification (23 countries were represented as at the end of the financial year) were therefore brought sharply into focus by virtue of its ability proactively to adjust the portfolio, such that the majority of holdings increased or maintained their dividends. Across the trust’s financial year, of the top 10 holdings, nine increased their dividends whilst one maintained its payout, reinforcing the fact that not all companies have been impacted in the same way by the pandemic.11 Pharmaceuticals, food producers/retailers, technology, utilities and telecoms proved more resistant to cuts, for example, whilst auto manufacturers, airlines, tourism, leisure, oil and gas, and banks cut sharply.

As the pandemic has worn on, its impact on the dividend-paying capacity of the world’s companies has become markedly clearer, as discussed in the recently published annual edition of the Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index. The third quarter of 2020 saw total payouts fall by $55bn to $329.8bn, the lowest since 2016 – this 14.3% headline decline was equivalent to a fall of 11.4% on an underlying basis, far better than Q2’s 18.3% decline. Overall, more than two-thirds of companies increased dividends or held them steady in Q3.12 The smaller impact primarily reflects a geographic mix in the third quarter that is skewed towards parts of the world where dividends have proved more resilient, but it is also an indication that the worst is past. Many companies that have traditionally paid a high portion of their profits in dividends, most commonly in countries like the UK and Australia, and to a lesser extent Europe, have now reset their payouts at a lower level, providing a firmer basis for future growth.

These are challenging times for the world. There is no modern precedent for a pandemic such as this one, but both Lowland and Henderson International Income are well-equipped to weather periods of economic uncertainty and to take advantage of opportunities as they arise. UK interest rates are likely to remain at, or close to, current lows and, against this backdrop, the objective of delivering an appealing income from a strategically diversified portfolio of holdings remains highly relevant. The uncertainty has left large parts of the market looking attractively valued from a historical perspective and a selective approach should allow for investment in leading companies with strong balance sheets that are able to fund their dividends while investing intelligently for the future.

1Source: Bloomberg, 10.12.20

2Calendar years 1991 to 2020 inclusive

301.01.2000 to 18.12.2013

4Source: Wellington Management and Hartford Funds, 02/2020

5Source: AJ Bell, Dividend Dashboard Q1 2021

6Source: Lowland Investment Company PLC, Factsheet – As at 30.04.2021

7 Source: Lowland Investment Company PLC, Annual Report 2020

8Source: Ycharts, 30.04.21

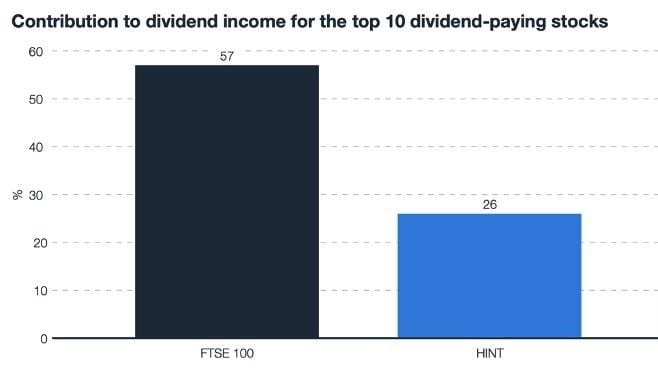

9Source: Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index, Link Group UK Dividend Monitor, for the year to 31.12.19; HINT dividend contribution for the 12 months to 31.08.20

10 Source: Henderson International Income Trust plc – Janus Henderson Investors – As at 01.06.21

11Source: Henderson International Income Trust PLC, Annual Report 2020

12 Source: Henderson International Income Trust PLC, Half-year Report 2021

13Source: Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index, Edition 30 – May 2021

Bear market ExpandA financial market in which the prices of securities are falling. A generally accepted definition is a fall of 20% or more in an index over at least a two-month period. The opposite of a bull market

Bottom-up ExpandBottom-up fund managers build portfolios by focusing on the analysis of individual securities, in order to identify the best opportunities in their industry or country/region.

Capital growth ExpandCapital growth, or capital appreciation, is an increase in the value of an asset or investment over time. Capital growth is measured by the difference between the current value, or market value, of an asset or investment and its purchase price, or the value of the asset or investment at the time it was acquired.

Discount ExpandWhen the market price of a security is thought to be less than its underlying value, it is said to be ‘trading at a discount’. Within investment trusts, this is the amount by which the price per share of an investment trust is lower than the value of its underlying net asset value. The opposite of trading at a premium.

Diversification ExpandA way of spreading risk by mixing different types of assets/asset classes in a portfolio. It is based on the assumption that the prices of the different assets will behave differently in a given scenario. Assets with low correlation should provide the most diversification.

Inflation ExpandThe rate at which the prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. The CPI and RPI are two common measures. The opposite of deflation.

Linear correlation/relationship ExpandA linear relationship (or linear association) is a statistical term used to describe a straight-line relationship between two variables. Linear relationships can be expressed either in a graphical format where the variable and the constant are connected via a straight line or in a mathematical format where the independent variable is multiplied by the slope coefficient, added by a constant, which determines the dependent variable.

Multi-cap ExpandThe ability to invest in stocks across market capitalization. That is, the portfolio comprises of large cap, midcap and small cap stocks.

Premium ExpandWhen the market price of a security is thought to be more than its underlying value, it is said to be ‘trading at a premium’. Within investment trusts, this is the amount by which the price per share of an investment trust is higher than the value of its underlying net asset value. The opposite of discount.

Sovereign bonds ExpandBonds issued by governments and can be either local-currency-denominated or denominated in a foreign currency. Sovereign debt can also refer to the total of a country’s government debt. They may also consider economic and asset allocation issues, known as top-down factors, but these are not of primary importance.

Valuation Expand

Valuation is the analytical process of determining the current (or projected) worth of an asset or a company. There are many techniques used for doing a valuation. An analyst placing a value on a company looks at the business’s management, the composition of its capital structure, the prospect of future earnings, and the market value of its assets, among other metrics.

Value investing ExpandValue investors search for companies that they believe are undervalued by the market, and therefore expect their share price to increase. One of the favoured techniques is to buy companies with low price to earnings (P/E) ratios. See also growth investing.

Yield ExpandThe level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For equities, a common measure is the dividend yield, which divides recent dividend payments for each share by the share price. For a bond, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.