Markets are built upon a healthy tension among participants in pursuit of ultimately arriving at an equilibrium suitable for all. Over the past few months, an acute source of tension has created a disconnect between the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) expected trajectory for its overnight policy rate and what forward-looking markets believed was appropriate, with the former remaining firmly in the restrictive camp. Wednesday’s statement by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell relieved much of that tension as the U.S. central bank took what we consider to be an unambiguous move toward dovish territory for the first time this cycle.

As evidenced by the precipitous post-announcement decline in bond yields across the U.S. Treasuries curve – 2-year yields fell by as much as 30 basis points (bps) and the 10-year by roughly 18 bps – the market embraced the Fed’s new posture. And while a shift in rhetoric does not equal a pivot, the intent of the central bank’s forward guidance is to lay the groundwork for what looks to be an imminent move.

JHI

This shift in the Fed’s stance has considerable implications for the fixed income landscape. Foremost, given Chairman Powell’s laser focus on price stability after 2022’s botched transitory call, the Fed would not even hint that a pivot – much less a 75-bps reduction – was in the cards unless it believed the inflation genie was being placed back in the bottle. If anything surprised us in the Fed’s statement, it was Chairman Powell’s seemingly abrupt reversal in his stance that rate cuts would not be forthcoming until inflation dipped closer toward the Fed’s 2.0% objective.

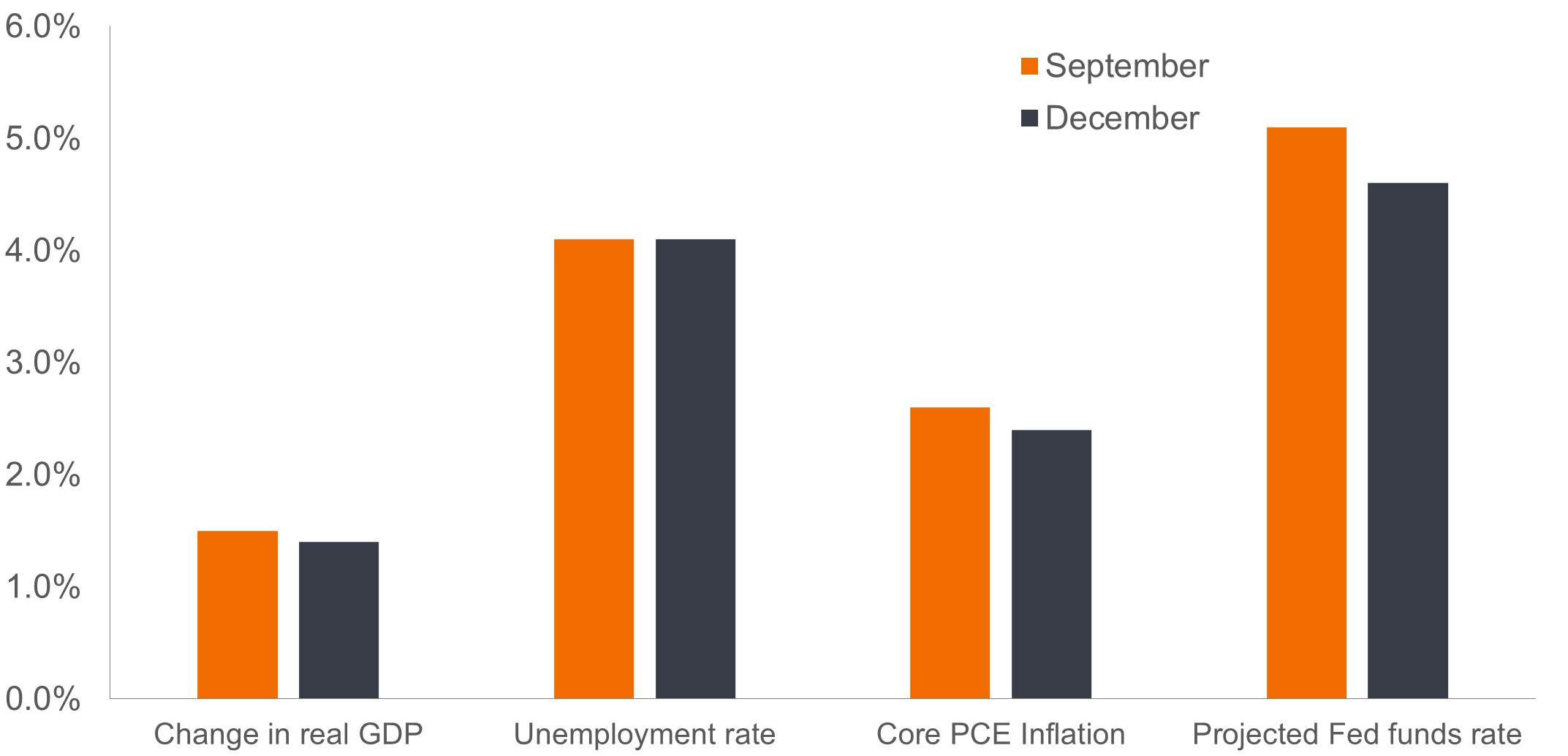

Change in Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (2024)

The Fed evidently has enough confidence in the continued descent of core inflation – expecting it to fall to 2.4% by year-end 2024 – to suggest that up to three 25-bps rate cuts may be justified over the next 12 months.

Source: Federal Reserve, as of 13 December 2023.

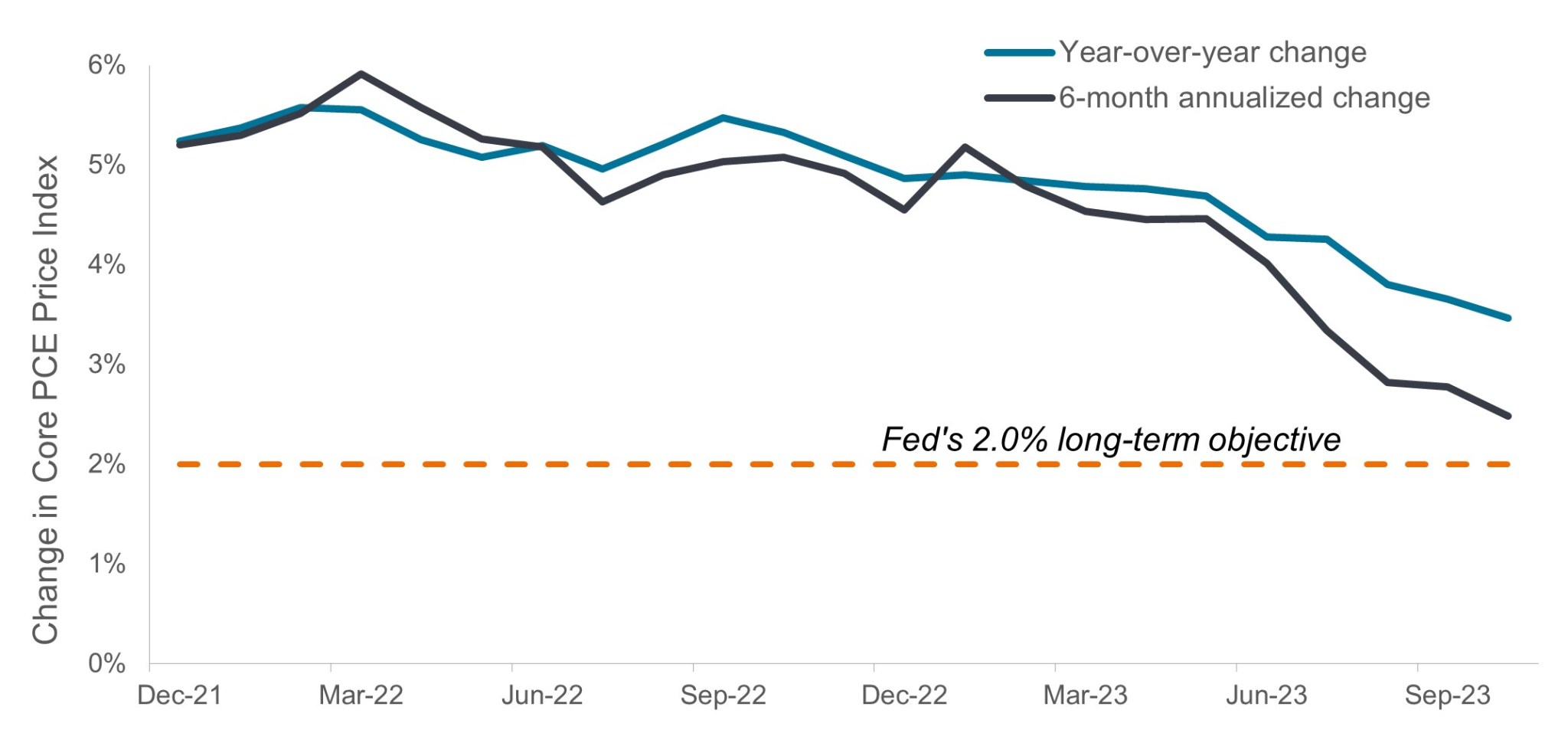

Granted, progress has been made. The Fed’s updated Summary of Economic Projections lowered its expectation for year-end 2024 core inflation, as measured by the Fed’s favored gauge, from 2.6% to 2.4%. We are already seeing this view play out, with the six-month annualized rate of inflation, based on the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE)1 price index, falling from 4.0% in June to 2.5% in October. Still, the central bank’s willingness to depart from this restrictive line in the sand is notable, although it could be second-guessed should inflation’s downward trajectory stall.

The welcome descent in inflation

Giving the Fed cover to shift to a dovish stance was the 6-month annualized inflation rate sliding to 2.5%, compared to a more elevated year-over-year figure.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 13 December 2023.

It’s working (maybe)

A soft landing is notoriously difficult to achieve. It’s the goal in nearly every tightening cycle, yet it seldom plays out that way. The current cycle is further complicated by the historic amount of accommodative policy unleashed by the Fed and other central banks in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, the data are supportive of an economy cooling at a manageable pace.

While job growth remains above trend, it has moderated from its post-pandemic peak. Other data indicate that fourth-quarter U.S. economic growth is well off its torrid 5.2% third-quarter pace. The Fed is now calling for 2024 gross domestic product growth to clock in at 1.4%, slightly down from September’s estimate of 1.5%. For reference, consensus estimates call for annualized quarterly economic growth to slow over the course of 2024 as the long and variable lags of 525 bps of previous rate hikes continue to bite. Importantly, these estimates do not call for any quarter to generate negative growth.

An early present for bond investors?

In our 2024 Market GPS, we argued that the upcoming year was shaping up well for bond allocations. This more-dovish-than-expected Fed statement reinforces our argument. Moderating economic growth means that a peak in the rates cycle has been reached. Importantly, a fixed income allocation can now offer yields at levels that had been absent for over a decade.

Furthermore, should a soft landing materialize, we believe higher-quality corporate and securitized credits could potentially offer value as their financial positions should help them weather a modest economic slowdown. If, however, growth surprises to the downside, we could see the safest segments of the bond market – namely Treasuries – rally across maturities. The resulting capital appreciation would then serve as a diversifier against the riskier equities and high-yield corporates that could likely experience a drawdown in a bearish scenario.

Mindful of the risks

While we see bonds likely performing well in both a soft landing and a more material contraction, there are risks inherent in our assessment of how Fed policy could impact the economy and the fixed income market.

Higher rates have stymied the U.S. housing market and business investment, and a lower cost of capital could provide relief to these rate-sensitive pockets of the U.S. economy. Should this development result in a positive-growth surprise, bond yields would likely find a floor, and those farther out on the curve could climb as investors price in higher growth and accompanying inflationary pressure.

Yet, as long as accelerating prices remain relatively contained, this is not a bad problem to endure as it is premised on resilient economic growth. Should that scenario materialize, we would expect more cyclical and lower-quality fixed income securities to also participate in any rally, as they could again grow revenues and maintain margins.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Securitized products, such as mortgage- and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed-income securities.

1 The personal consumption price index for both headline and core (ex food and energy) categories track the price changes in goods and services purchased by consumers over a given period and is the favored measure of inflation of the Federal Reserve when referencing year-over-year figures.

2-Year Treasury Yield is the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bonds that will mature 2 years from the date of purchase.

10-Year Treasury Yield is the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bonds that will mature 10 years from the date of purchase.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Quantitative Tightening (QT) is a government monetary policy occasionally used to decrease the money supply by either selling government securities or letting them mature and removing them from its cash balances.

U.S. Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the U.S. Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and U.S. Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

A yield curve plots the yields (interest rate) of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. Typically bonds with longer maturities have higher yields.