Where are we headed in 2025? Uncertainty reigns, and we break out the telescope to do some stargazing. Importantly, we will talk about change. Markets respond to change, not level, and there is potential for plenty of change in 2025.

The economy and inflation

The economy is doing fine globally and gaining some near-term momentum in the U.S. Even slow-growth regions like Europe and China show little danger of plummeting into recession. Certain elements – such as tariffs – can redistribute growth, but they should have less effect on aggregate global growth. The same holds true for tax cuts. In summary, we expect growth to moderate somewhat in 2025. Disinflation, a tailwind for the last 18 months, is largely behind us. Major central banks (outside Japan) will continue easing in the near term, although a failure to meet inflation targets in the U.S. will likely force a pause by the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) in the first half of 2025.

The Republican party’s clean sweep in the U.S. election rewrites the rules and will have important global implications. Some combination of tariffs, an extension of tax cuts, and the introduction of some new tax cuts is a near certainty. Immigration reforms should be a bigger worry than tariffs and could substantially slow jobs growth in the next two to three years. Add in deregulation, and the most likely net effect is a modest deceleration in U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Already, however, there is a substantial push to cut spending that was not part of the original platform. Aggressive spending cuts are unlikely to arrive before the second half of 2025 but would hinder growth prospects if they arrive.

There will almost certainly be an extension of the tax cuts enacted in the first Trump administration, most likely in the first quarter of 2025. An extension will have limited impact on the fiscal impulse, which is already poised to exhibit a small contraction in 2025. Corporate tax rates in the U.S. may be lowered – although the proposal to move them from 21% to 15% may struggle to gather sufficient momentum.

Lower corporate taxes will not materially boost growth (although the Inflation Reduction Act – through the tax code – has helped redirect investment toward clean energy projects). Theory holds that a lower tax rate unleashes investment. This does not happen in capital-rich economies, as seen in previous tax reduction episodes. Developing economies do not lack access to capital; they already have the means to undertake projects that are economically additive. Lower taxes will increase after-tax profits, however, and play an important role in shifting wealth to the owners of capital.

Figure 1: Weak link between low corporate tax and higher investment

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, OECD annual investment by non-financial and financial corporations as a % of GDP (2022), combined corporate tax rates (2022). Combined corporate tax is central government or federal level corporate tax rate plus an adjustment for state/regional level taxes, e.g. U.S. federal tax is 21%, but average state taxes lift this to nearly 26%. 2022 is used as the comparison year as this provides the latest available complete figures across most OECD countries. Dotted trend line indicates limited link between low tax rate and higher investment.

The effect of tariffs is highly variable as it depends on whether costs are passed through to consumers, currency exchange rate movements, and the level of retaliation. A 60% tariff on Chinese imports and 10% tariffs on the rest of the world may shave 1%-2% from Chinese growth and circa 0.4%-0.8% from U.S. and rest-of-world growth by 2026.1

As tariffs are easily reversible, they tend not to spur expensive, long-term projects to onshore jobs. Much of the fear – and potential impact – is overstated. The more extreme projections are unlikely to be fully implemented.

A note on tariffs and capital flows

Tariffs are not a straightforward policy tool. They can mitigate trade imbalances, simply by making imports more expensive. This has the effect of reducing a trade deficit, but this may not always be a net benefit. A trade deficit, by definition, is offset by a capital account surplus. The U.S. is the world’s largest net borrower of foreign capital, i.e. foreigners invest more in the U.S. than the U.S. invests overseas, creating a capital inflow to the U.S. This is a good thing, as it allows the country to put the capital to productive use. The virtuous circle allows consumers to import foreign goods, sending dollars abroad. These dollar payments are then reinvested through the capital account.

The impact of tariffs on inflation is misunderstood. While tariffs force prices higher as they are passed onto consumers, unless there are secondary effects, it is a tone-off move up in the price level rather than a sustained rise in inflation. Higher inflation figures make a central banker’s job more difficult, but markets tend to look past a tariff-induced rise in inflation and view it as a one-off adjustment.

A disruption in the flow of funds is a greater threat than high trade deficits. The U.S. needs the dollars received by trade partners to be recycled. Trade restrictions without economic growth to accompany them might produce higher deficits and a need for higher interest rates to attract flows.

Inflation: Weak gravity

Inflation has been on a steady trend downward. Supply bottlenecks were the first to dissipate following the pandemic. Next came goods prices, and then rents. Rents can moderate further but that may be the end of the good news. Services prices remain sticky and are now heading up. As rent inflation stops declining in the next two to three months, a new challenge may emerge as the economy loses its convenient offset to sticky services prices. Tariffs would further exacerbate the trend.

The Fed has expressed confidence that inflation is retreating to their 2% target. Much of this is because of the well-established trend in their preferred metric – core personal consumption expenditure (PCE). The Fed’s confidence may be misplaced, because PCE may be understating the underlying pace of price increases. Trade friction and tariffs will likely push U.S. inflation up and keep it above the 2% target.

The neutral rate of interest (R-star or R*)

R* is defined as the real rate of interest which is neither expansionary nor contractionary. If R* is 1% and target inflation is 2%, then theoretically policy interest rates would need to be at 3% for the economy to be in balance. The idea is to achieve satellite orbit at full employment and then find the proper neutral rate. With a satellite, too high a velocity (speed it takes to travel in a straight line) and it drifts into space; too low and it crashes to earth. With interest rates, too high an interest rate risks recession, while too low a rate risks inflation.

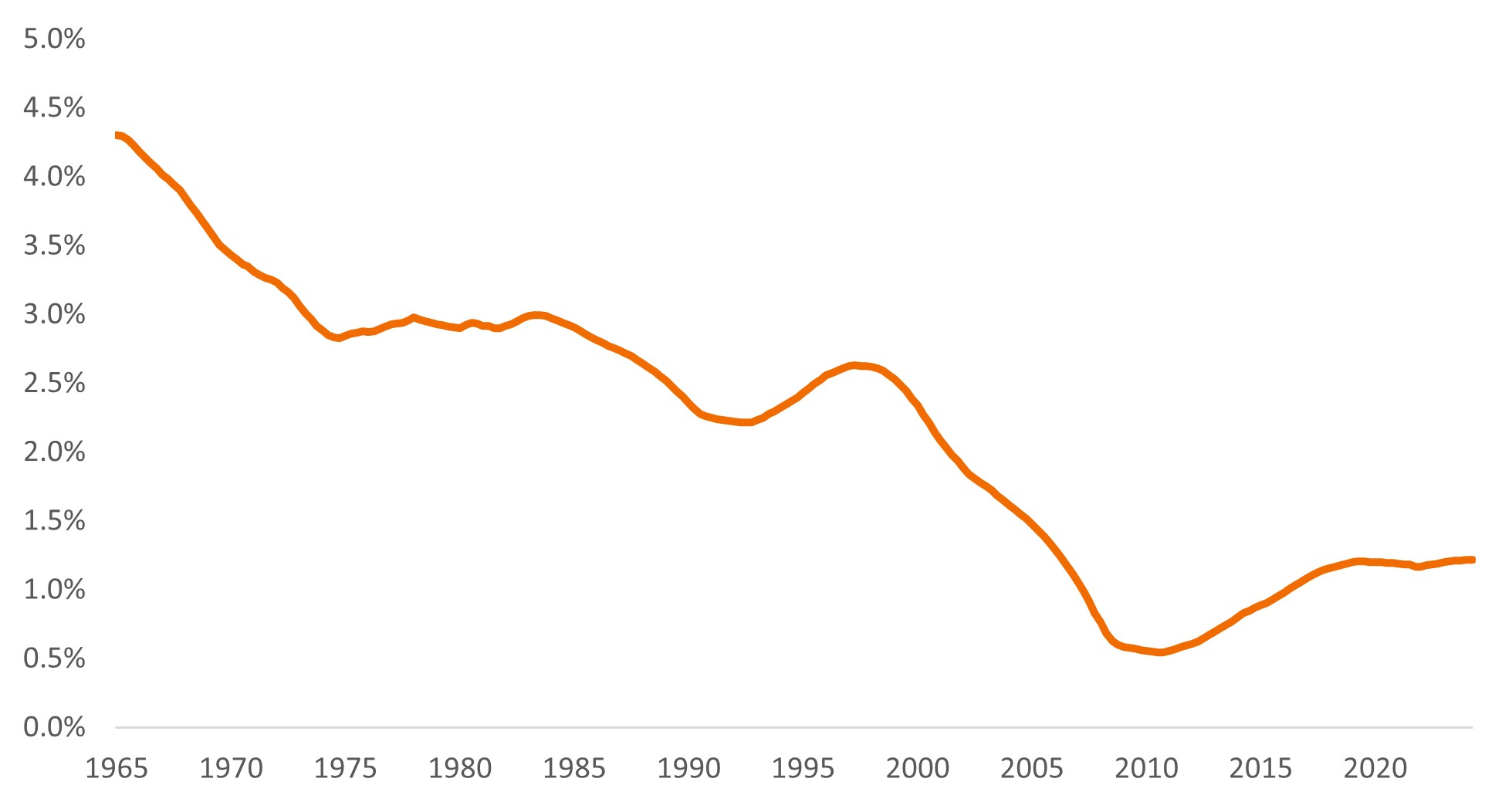

The problem with a neutral rate is that it is not observable, although we do know it has gone higher. The Fed does not really know by how much but has estimated that neutral policy rates have moved up and has moved its (long-term) federal funds rate expectations from circa 2.5% five years ago to 2.9% in recent years. R* bottomed after the 2008/’09 Global Financial Crisis but has risen on the heels of long-term factors such as demographics and a rise in productivity. The pool of global excess savings, long a suppressant on global rates, is shrinking as more economies lean on dis-saving (i.e., budget deficits). Cyclical factors are also at work.

Figure 2: U.S. neutral rate of interest or R-star

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Laubach-Williams Two Sided estimates, Q1 1965 to Q2 2024.

If R-star is estimated to be at 1.22% recently and target inflation is 2%, this suggests a neutral policy rate around 3%-3.5%. With the fed funds interest rate at 4.5%-4.75% in November 2024, does this mean U.S. monetary policy is restrictive? And how does this square with a relatively strong U.S. economy?

There are three possible reconciliations: 1) lags mean the economy is not yet reflecting the restrictive level of rates, 2) GDP growth has been respectable, but restrictive policy is manifesting itself through the unemployment rate, which has been trending higher; 3) fiscal policy has been stimulatory and offset some of the restrictiveness. This latter point is another reason why the Fed is likely to cut rates at a moderate pace.

A looming black hole

Debt sustainability issues have resurfaced. How much debt is too much? This is a difficult question to answer because it depends on whether debt is productive or not. Deficits, as a percentage of GDP, will be unusually high in developed economies but need not cause a crisis. Like all markets, the greater supply of debt will force rates higher, all else equal – but all else is not equal. The supply of global excess savings can also grow, keeping rates in equilibrium.

The full range of proposed tax cuts and tariffs, if enacted, may lead to fears that deficits will become intractable later in 2025. It is more likely, however, that only a portion of proposals are enacted. The pace of borrowing may appear reckless, but a day of reckoning in the coming months appears unlikely.

Europe will see a different set of patterns play out. The European Central Bank (ECB) is set to end Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) reinvestments in 2025. Gross supply of bonds will have to be met by demand from the private sector and could lead to higher term premia. Meanwhile, an anticipated decline in the combined budget deficit across Eurozone countries – from 3.6% of GDP in 2023 to 3.1% in 2024 and 2.8% in 2025 – will create an economic drag just when potential tariffs kick in.2 Monetary policy will have to work harder in the eurozone to support Europe’s economy, leading to deeper interest rate cuts.

Dark matter: The role of deficits

Scientists cannot explain many astronomical phenomena and have hypothesised that dark matter, currently unobservable, must exist to account for certain gravitational effects and explain the formation of galaxies. A curiosity in bond markets in recent years has been the low level of defaults. The answer is more prosaic than dark matter: government largesse.

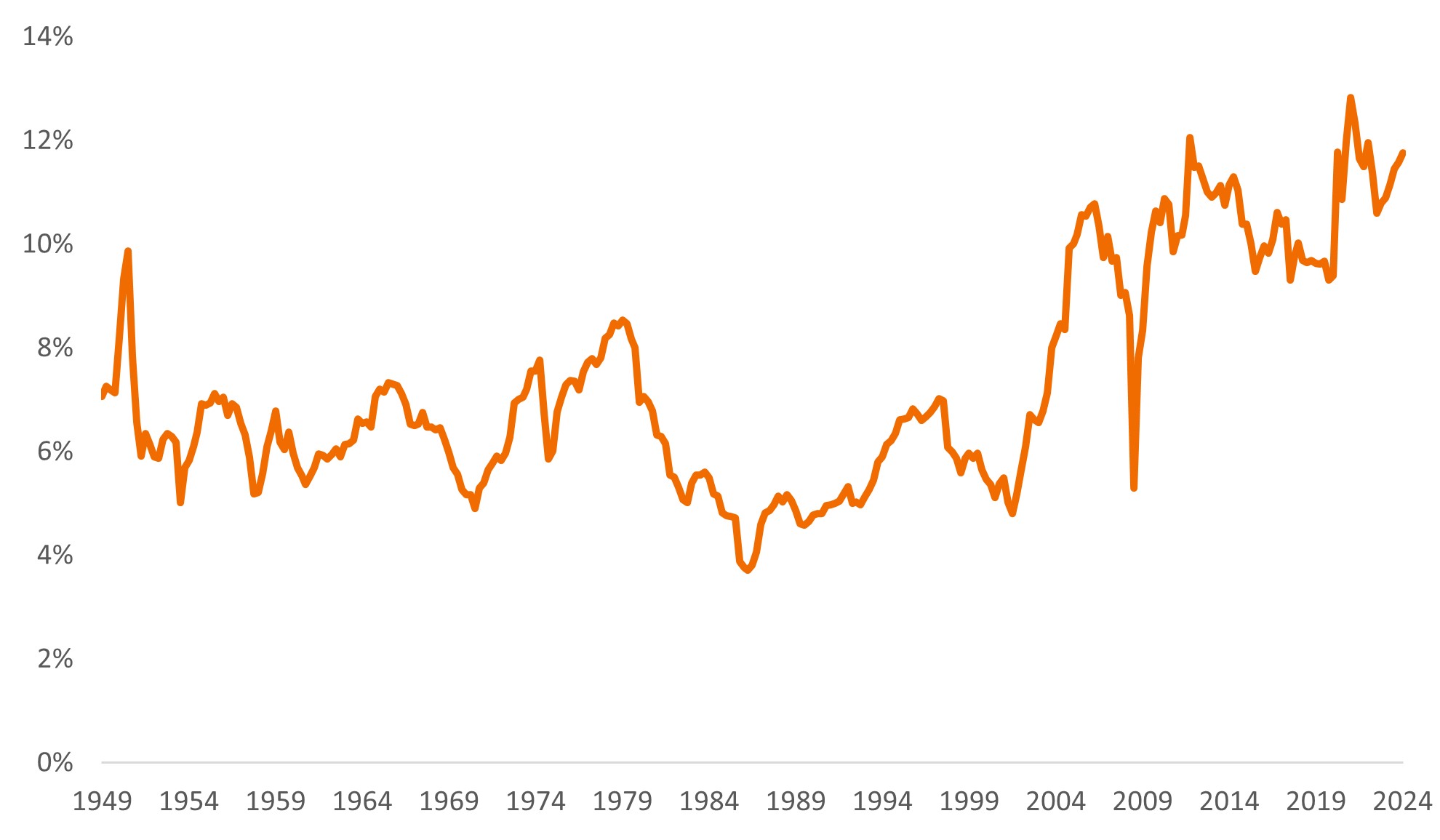

A deficit cannot exist in a vacuum. One person’s deficit is another’s surplus. This is the good side of deficit financing, and the part that is often under-recognized. Government deficits should support corporate profits.

Companies may get more help from tax cuts, but they don’t really need the assistance. Demand for corporate debt is strong, and attractive yields have lured investors.

Figure 3: U.S. corporate profits as a percentage of U.S. GDP are already elevated

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data (FRED), corporate profits after tax/Gross Domestic Product, Q2 1949 to Q2 2024.

We expect corporate default rates to stay relatively low in 2025. Nearly every part of the story is supportive of credit: Fundamentals are strong, private credit is providing an additional source of financing, and central banks are cutting policy rates.

Should the full weight of tariffs unfold, Europe, China and Mexico are most at risk. Deregulation will be good for profits but will also encourage more shareholder-friendly (and less bondholder-friendly) activity in the year ahead. An acceleration in merger and acquisition activity is highly likely.

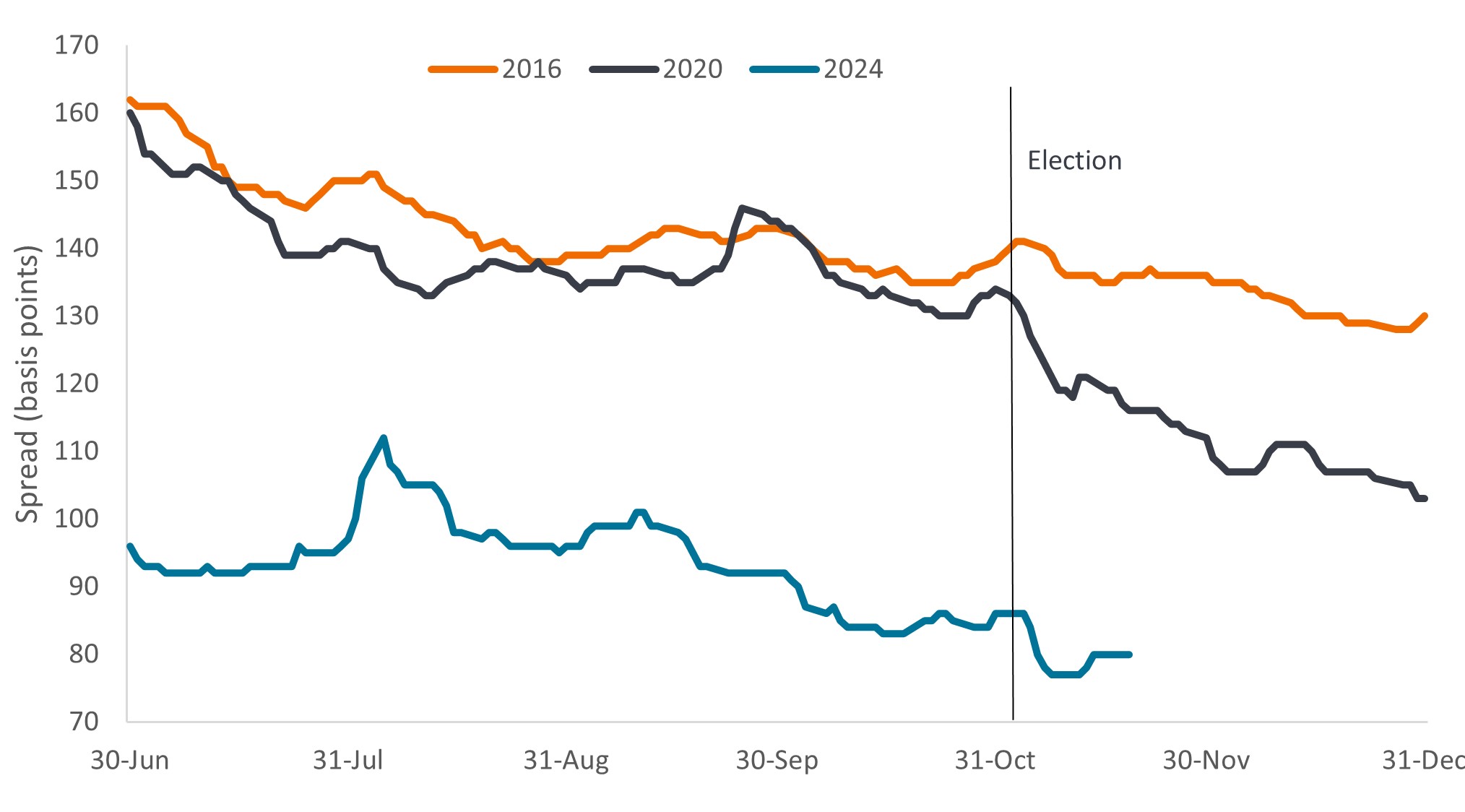

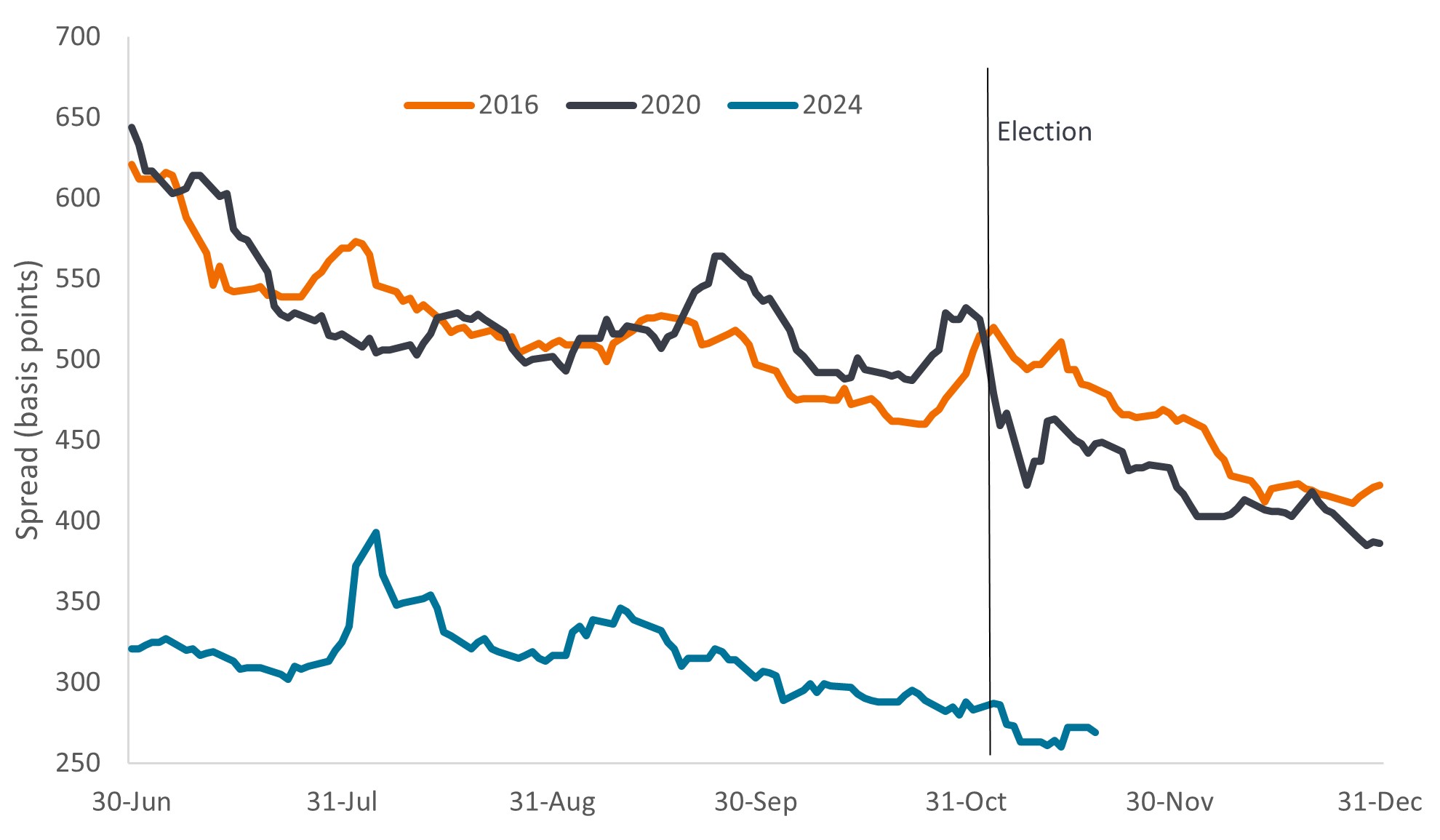

Sadly, there is no free lunch. Credit spreads (the additional yield a corporate bond pays over a government bond of the same maturity) have moved to near cycle tights in U.S. corporate bonds, although less so among loans and mortgage-backed securities or in European corporate debt. There is therefore limited prospects for capital gains from spreads moving tighter, but also little danger of credit stress in the near term. At this stage, history suggests the spoils will accrue more to equity holders than to creditors. We look for calm in early 2025, but the evolution of the credit cycle (as higher refinancing costs overwhelm some of the more indebted borrowers) will likely cause issues later in the year.

Figure 4a: Investment grade spread tightening post U.S. elections

Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index (C0A0), Govt option-adjusted spread (Govt OAS), final six months of election years. 2024 is to 19 November 2024. Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Figure 4b: High yield spread tightening post U.S. elections

Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index (H0A0), Govt option-adjusted spread (Govt OAS), final six months of election years. 2024 is to 19 November 2024. Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

The great provider

Our own star – the sun – provides us with warmth and energy. We are not about to advocate worshiping bonds as the ancients did the sun, but bonds have advantages – namely reliable income and diversification. Yields are at attractive levels relative to history, and government bonds could offer a potentially useful counterweight against equity market volatility.

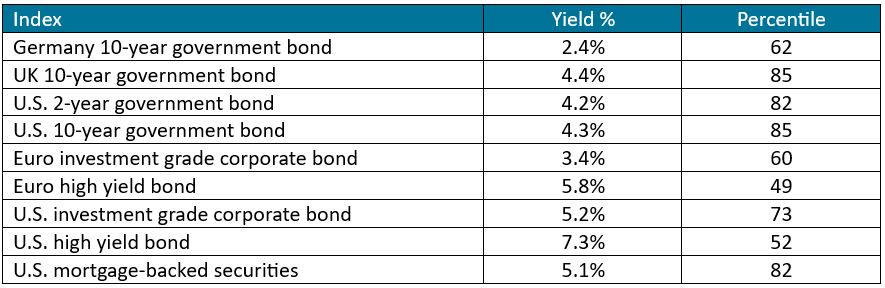

Figure 5: Yields and their percentiles over a 20-year period (to 31 October 2024)

Source: Bloomberg. ICE BofA indices. Yields are as at 31 October 2024. The percentile range ranks each month end yield figure over the last 20 years to October 2024. The percentile figure is out of 100. A percentile of 100 means the yield was the highest yield over the period, a percentile of 1 means the yield was the lowest over the period. A percentile of 62 means yields for the asset type have been lower 62% of the time and higher 38% of the time over the last 20 years. Yields for government bonds are yield to maturity. Yields for other indexes are yield to worst. Definitions and indexes used are given below. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Central bank easing will provide an important support for bonds, but our view is that rates will remain higher than they have been. Inflation has bottomed, tariffs are around the corner, and international capital flows are becoming less supportive. Government debt levels and the supply of credit are inexorably rising. These are all reasons for rates to remain higher, but we should not confuse that with reasons for rates to continue rising. Ten-year U.S. Treasuries offer value at 4.3%, just as 10-year German bunds offer value at 2.4%.3 We believe investors should be overweight interest rate duration.

We also believe investors should diversify their fixed income holdings, taking advantage of appealing yields. The role of bonds as a portfolio diversifier should reassert itself and provide ballast to portfolios in this new environment. In our view, it is important to think broadly in terms of asset allocation. Securitized assets appear particularly attractive, as are pockets of emerging market debt. As spreads move tighter, a greater cross-section of assets will be beneficial. Dispersion should remain high, and security selection will remain at a premium.

Safe travels as you seek your North Star. Be aware that risk may play out very differently depending on the sequencing of policy. Like a satellite in orbit, things look supportive today, but there is a danger we may get bumped off course.

1Source: UBS Global Research, 18 November 2024.

2Source: Bloomberg, Consensus economic forecasts, 19 November 2024.

3Source: Bloomberg, Generic Government 10-year bonds, 31 October 2024.

Basis points: Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Corporate fundamentals are the underlying factors that contribute to the price of an investment. For a company, this can include the level of debt (leverage) in the company, its ability to generate cash and its ability to service that debt.

Credit rating: A score given by a credit rating agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s and Fitch on the creditworthiness of a borrower. For example, S&P ranks investment grade bonds from the highest AAA down to BBB and high yields bonds from BB through B down to CCC in terms of declining quality and greater risk, i.e. CCC rated borrowers carry a greater risk of default.

Credit spread. The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Disinflation: A fall in the rate of inflation.

Diversification: A way of spreading risk by mixing different types of assets/asset classes in a portfolio, on the assumption that these assets will behave differently in any given scenario. Please note diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing losses.

Duration: A measure of the sensitivity of a bond’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa. Bond prices rise when their yields fall and vice versa.

Federal Reserve (Fed): The central bank of the US which determines its monetary policy.

Fiscal policy: Describes government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels.

Fiscal impulse: The change in the government primary deficit (which excludes net interest payments) from one year to the next. A positive fiscal impulse is stimulatory for the economy, while a negative fiscal impulse is seen as contractionary.

Gross domestic product (GDP): The value of all finished goods and services produced by a country, within a specific time period (usually quarterly or annually). GDP is a broad measure of the size a country’s economy.

High yield bond: Also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

The ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index (ER00) tracks the performance of EUR denominated investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the Eurobond or Euro member domestic markets.

The ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index (HE00) tracks EUR denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the euro domestic of eurobond markets.

The ICE BofA US Corporate Index (C0A0) tracks the performance of US dollar denominated investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

The ICE BofA US High Yield Index (H0A0) tracks the performance of US dollar denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

The ICE BofA US Mortgage Backed Securities Index (M0A0) tracks US dollar denominated fixed rate residential mortgage pass-through securities publicly issued by US agencies Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae in the US domestic market.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy. The Consumer Price Index is a measure of inflation that examines the price change of a basket of consumer goods and services over time. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index is a measure of prices that people living in the US pay for goods and services.

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: A US federal act that contains spending and tax credits aimed at lowering prescription drug prices and promoting domestic energy production, notably in clean energy.

Investment grade bond: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments, reflected in the higher rating given to them by credit ratings agencies.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP): A temporary scheme operated by the European Central Bank to purchase public and private sector securities. It was initiated in March 2020 to counter risks to the Eurozone economy posed by the COVID outbreak.

Refinancing: The process of revising and replacing the terms of an existing borrowing agreement, including replacing debt with new borrowing before or at the time of the debt maturity.

Tariff: A tax or duty imposed by the government of one country on the import of goods from another country.

Term premia: This is the extra return that investors demand to hold a longer-term bond instead of investing in a series of short-term bonds. It is the compensation investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Yield to maturity: The total rate of return earned when a bond makes all interest payments and repays the original principal.

Yield to worst: The lowest yield a bond (index) can achieve provided the issuer(s) does not default; it takes into account special features such as call options (that give issuers the right to call back, or redeem, a bond at a specified date).

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) may be more sensitive to interest rate changes. They are subject to extension risk, where borrowers extend the duration of their mortgages as interest rates rise, and prepayment risk, where borrowers pay off their mortgages earlier as interest rates fall. These risks may reduce returns.

Securitized products such as mortgage- and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed income securities.

Past performance does not predict future returns. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue or forecasts will be realized.

References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.