| The JH Explorer series follows our investment teams across the globe and shares their on-the-ground research at a country and company level. |

From oil to bonds: Saudi Arabia’s bold charge into global debt markets

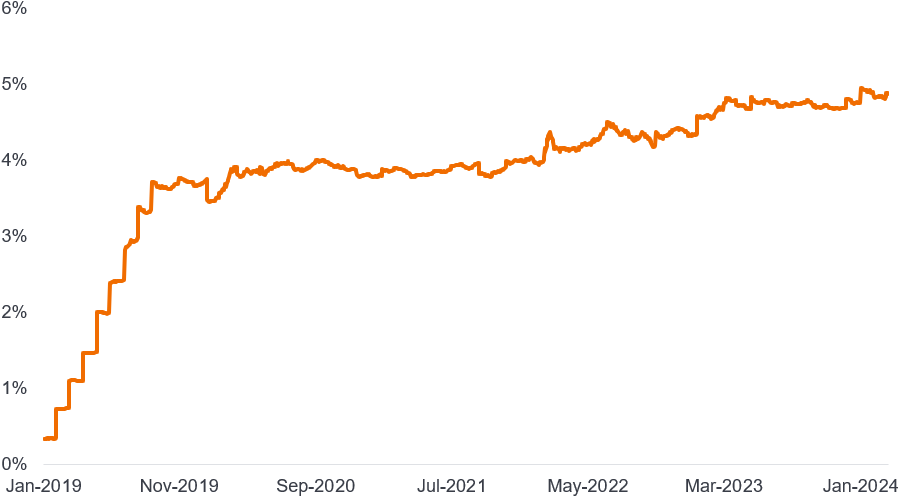

Until 2016, Saudi Arabia was off-the-radar of mainstream emerging market (EM) bond investors given its lack of FX-denominated sovereign debt. All that changed in October of that year when the Kingdom sold US$17.5bn of bonds in one-go, the largest-ever emerging market bond sale. Since then, the steady supply of Eurobonds from the sovereign and the Public Investment Fund (the country’s sovereign wealth fund) has triggered a rise in Saudi Arabia’s benchmark weight. As of 2 April 2024, Saudi Arabia is the second largest country in the emerging markets debt hard currency (EMD HC) investment universe after Mexico with a weight just shy of 5%.1

Figure 1: Saudi Arabia’s EMBIGD index weight

Source: Janus Henderson Investors and Macrobond. Data is from 31 January 2019 to 2 April 2024.

The Kingdom’s strategic approach to debt issuance, characterised by a mix of conventional bonds and sukuk (Islamic bonds), demonstrates a nuanced understanding of market dynamics and investor preferences. As it continues to navigate the complexities of economic diversification and development, Saudi Arabia’s future issuances will likely be closely watched by international investors. The continued development of its local debt market, along with the potential inclusion in the GBI-EM index, signals a positive trajectory for the kingdom’s financial markets that would help attract more foreign portfolio investment.

Beyond oil: Saudi Arabia’s bold bet on economic diversification

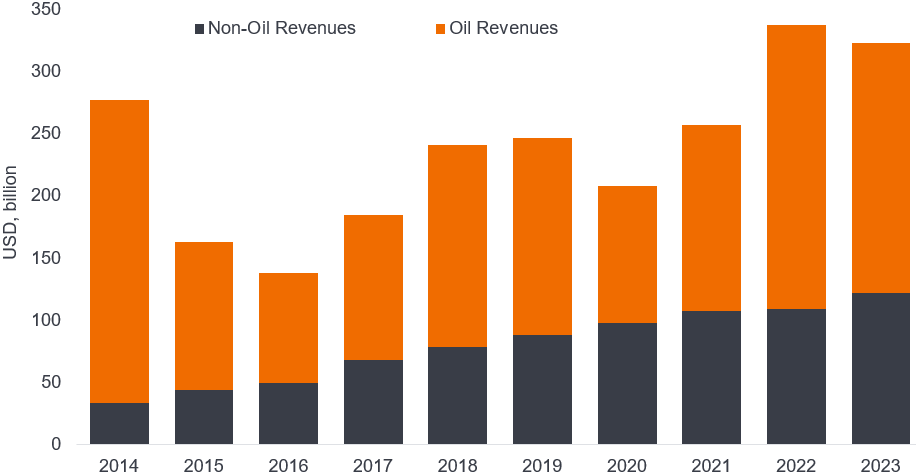

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 represents a significant shift in the kingdom’s economic strategy, aiming to diversify its economy away from oil dependency. Spearheaded by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman this initiative outlines a series of ambitious goals, including the development of several “giga-projects” like NEOM, the Red Sea Tourism Project and Qiddiya. These projects are part of a broader effort to stimulate various sectors of the economy – from tourism to technology, to attract foreign investment, reduce oil dependence, and increase the share of non-oil revenues in the government’s budget (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Saudi Arabia’s government revenue

Source: Janus Henderson Investors and Macrobond. Data from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2023. Note: Over the past decade, non-oil revenues have increased nearly four times, reaching over US$120bn in 2023 and are forecasted by the Ministry of Finance to grow to US$150bn this year.

In early March, the country’s tech ambitions came into sharp focus during the international tech conference, LEAP 2024, hosted in Riyadh. The conference concluded with investment pledges amounting to over US$13bn and news of a planned tech fund worth US$40bn earmarked for investments in artificial intelligence. If the plan materialises, it will position Saudi Arabia as one of the world’s largest AI investors.

One of the significant challenges of Vision 2030 is maintaining a delicate balance between promoting private sector growth and the expansive role the Public Investment Fund (PIF) plays across various economic sectors. As it aggressively forays into numerous industries, from renewable energy to entertainment and sports, there’s a growing concern over PIF’s dominance potentially crowding out private investment, stifling competition and innovation.

The pivotal role PIF has in bringing Vision 2030 to life was reinforced after our trip, when Aramco announced the transfer of 8% of its shares (worth over US$160bn) from the government, doubling the SWF’s stake in Saudi Arabia’s crown jewel.2 In conjunction with dividends from existing investments, capital gains and further asset transfers, PIF aims to breach the US$1trn assets under management (AuM) milestone by the end of 2025 and reach US$2trn by 2030.

Gigaprojects unveiled: Saudi’s grand vision meets reality

In the heart of Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 lie its giga-projects; grandiose plans designed to vault the kingdom into a future far beyond its oil-rich past. NEOM, the US$500 billion crown jewel, promises a technologically advanced, sustainable city; a utopia of innovation where robots might outnumber humans and everything from utilities to transport is powered by renewable energy.

Then there’s the Red Sea Project, set to transform Saudi’s coastline into a luxury tourism destination to rival the likes of the Maldives, with its commitment to conservation and eco-friendly development. And not to be overlooked is Qiddiya, envisaged to become the largest cultural, sports, and entertainment city in the Kingdom, bringing a wave of leisure and creativity to the local population.

To say the giga-projects are ambitious would be an understatement. Evaluating them on an individual basis is essential, given the likelihood of future adjustments. Some projects may be revised if it turns out that their initial scope is too broad, or spending could be deferred if fiscal pressures intensify.

Notable developments such as the Bujairi Terrace within the Diriyah giga-project (the original home of the Saudi royal family), which was one of our site visits, the launch of new hotels along the Red Sea coast, and the impending inauguration of two theme parks in Qiddiya underscore the tangible progress being made.

Therefore, we expect the authorities to be flexible: doubling down on those projects that look to have the greatest potential for success and scaling down or tweaking others that fail to attract the expected demand.

A model of the ambitious Diriyah project. Portfolio manager Sorin Pirău visited a number of such giga-project sites, which lie at the heart of the Saudi Arabia’s ambitious vision to vault the country’s economy beyond oil dependency.

However, these shimmering visions of the future are not without their shadows. The sheer scale and ambition of such projects come with significant uncertainties and drawbacks. The question looms: can these futuristic cities and tourist havens attract the global audience they seek, and will they deliver the economic diversification and job creation promised?

Walking a geopolitical tightrope

Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 is not just an economic blueprint; it’s a strategy unfolding amidst a complex geopolitical landscape. Central to this is the delicate détente with Iran, offering a glimmer of regional stability but shadowed by historical mistrust and competing interests. This fragile peace is crucial, as enduring tensions could undermine the kingdom’s transformative economic goals. So far, spillovers from the Red Sea attacks on ships remained broadly contained with no Saudi vessel having been targeted by the Houthis.

Before the 7 October 2023 attack, Saudi Arabia was close to sealing a grand bargain that had the potential to completely overhaul the diplomatic landscape of the Middle East. This deal would entail the US supplying Saudi Arabia with civilian nuclear technology and robust security assurances through a formal defence treaty. In exchange, Saudi Arabia would establish diplomatic ties with Israel, while the latter would commit to significant progress towards the creation of a two-state solution.

The message we got on the ground was that the Kingdom’s commitment to normalise ties with Israel remains, but the bar to do so has gone up after the commencement of hostilities in Gaza. We also heard that domestic politics in the US will increase uncertainty in achieving the necessary two-third majority in the Senate for the US to approve a formal security treaty. In view of this, we expect geopolitics to continue playing an important role in shaping investors’ perceptions of the country’s credit risk in the years to come.

1 Saudi Arabia’s weight in the benchmark JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified (EMBIGD) stood at 4.88% (rounded) as of 2 April 2024. EMBIGD tracks liquid US dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities and is a widely followed benchmark.

2 Saudi Aramco, also called Aramco, is one of the world’s largest integrated energy and chemicals companies.

Credit risk. The risk that a borrower will default on its contractual obligations to make the required interest payments or repay the loan. Anything that improves conditions for a company can help to lower credit risk.

Diversification. A way of spreading risk by mixing different types of assets/asset classes in a portfolio, on the assumption that these assets will behave differently in any given scenario. Assets with low correlation should provide the most diversification.

Emerging market. The economy of a developing country that is transitioning to become more integrated with the global economy. This can include making progress in areas such as depth and access to bond and equity markets and development of modern financial and regulatory institutions.

Eurobond. A bond denominated in a currency not native to the country where it is issued.

Geopolitics. Politics, especially international relations, influenced by geographical factors.

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). A political and economic alliance of six Middle Eastern countries—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman – established in 1981. The aim of the GCC is to achieve unity among its members based on their common objectives and similar political and cultural identities.

JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD). A widely used benchmark, or investable universe proxy, for hard currency emerging market debt. This index tracks liquid US dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities.

JP Morgan Government Bond Index-Emerging Markets (GBI-EM). A widely used benchmark, or investable universe proxy, for emerging market debt issued in local (domestic) currency.

Saudi Vision 2030. An ambitious programme to transform the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Key aspects of the Vision 2030 transformation roadmap are reduced dependence on oil revenues, diversification of the economy and the creation of innovative economic growth and investment opportunities. Vision 2030 strategic objectives also include improving government effectiveness, improving employment opportunities, developing a strong social infrastructure and enhancing the quality of life for Saudi citizens.

Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). A special purpose investment fund or arrangement, owned by general government, that invests globally in a range of real and financial assets for financial objectives. SWFs are recognised as well-established institutional investors and important participants in the international monetary and financial system. SWFs are commonly established out of balance of payments surpluses, official foreign currency operations, the proceeds of privatisations, fiscal surpluses, and/or receipts resulting from commodity exports.

Sukuk. The Arabic name for Sharia-compliant bond-like instruments created with the intention of delivering returns similar to those of conventional fixed income instruments. The official definition provided by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), the Bahrain-based Islamic financial standard setter, for Sukuk finance is as follows: “Certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in the ownership of tangible assets, usufructs and services or (in the ownership of) the assets of particular projects or special investment activity.”

Important information

Past performance does not predict future returns.

References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Beta measures the volatility of a security or portfolio relative to an index. Less than one means lower volatility than the index; more than one means greater volatility.