A divided outlook

Against a benign global macro backdrop, broad-based monetary easing and improving credit risk in EM with no new defaults, 2024 has been a positive year for EMD HC. It delivered year-to-date total returns of nearly 8% and 56bps of spreads tightening at the index level (106bps if we exclude Venezuela, which re-entered the index)1. The resilience of EMD HC was underpinned by more than twice as many ratings upgrades as downgrades – the strongest ratings move since the global financial crisis – helped by a wave of idiosyncratic improvements in weaker-rated countries2. We expect credit quality to continue to improve, leaving EM resilient in 2025.

As we headed into the US election, the consensus was that a Trump win and a Republican sweep in Congress would be the worst-case scenario for EMs due to fears about punitive tariffs, tightening of immigration policies and fiscal easing. These policies would likely fuel inflation and pose challenges to growth outside the US, potentially leading to a stronger dollar and wider EMD HC spreads. However, since the election markets have turned more constructive, at least in the short term, and are now in wait-and-see mode for the new administration to take office. Stock markets have rallied on expectations of a stronger US economy, deregulation, fiscal easing and hope that the incoming administration will water down most of its election promises.

As we approach 2025, there is still a lack of clarity about US policies and their potential impact on the US economy, but also more broadly on the global economy. Here we draw lessons from history of the first Trump presidency and finally revisit the fundamentals for EM to assess the outlook for 2025.

Any lessons from Trump 1.0?

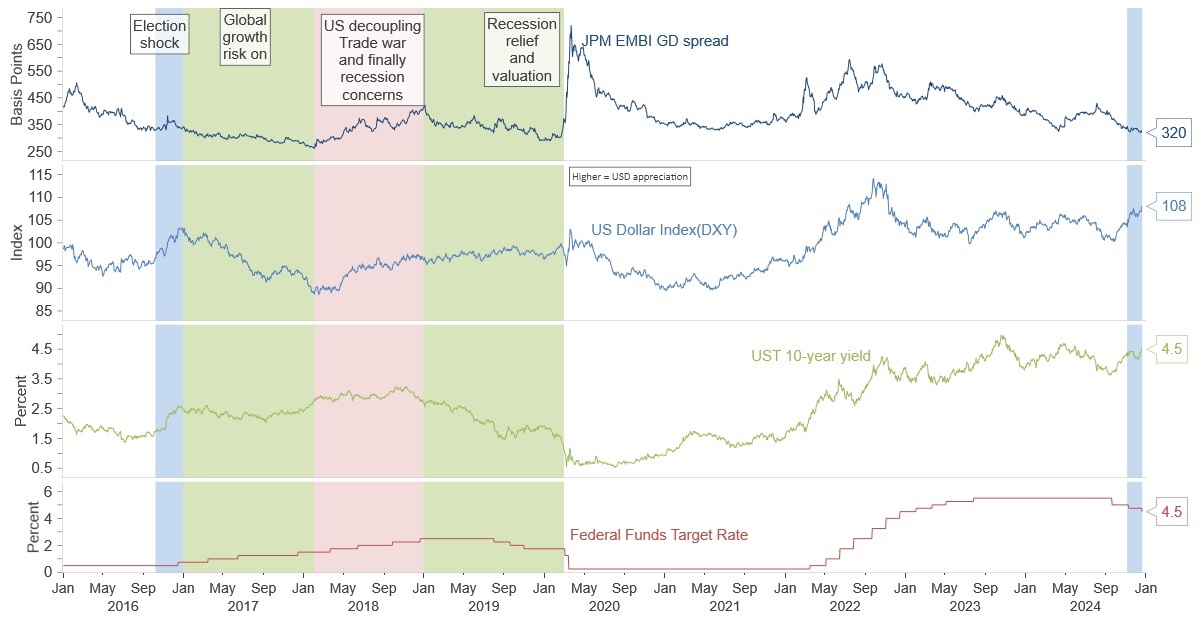

Following the 2016 election, EMD HC spreads tightened, and the dollar and US Treasury (UST) yields weakened throughout the first year of Trump’s term as the synchronised global recovery that started in 2016 continued and Trump’s pro-growth policies lifted sentiment (see Figure 1 below).

However, as pro-growth policies in the US kicked in more meaningfully in late 2017, the US started to decouple from the rest of the world, where economic growth was losing steam. The decoupling was further amplified when Trump launched tariffs causing trade tensions with China and Mexico. The trade war significantly hit sentiment outside of the US, spurring a stronger dollar, and wider EMD HC spreads as the EM-US growth differential was adjusted downwards.

2018 was a quite volatile year for EM that not only had to cope with US decoupling, but also US recession risks towards the end of 2018, which pushed EMD HC spreads higher and UST yields lower. With the significant re-pricing of the asset class throughout 2018, valuations became attractive enough in 2019 to resume spread tightening as recession risks subsided in the US, and the US Federal Reserve (Fed) pivoted to rate cuts, which saw UST yields fall. That largely lasted until the onset of the pandemic.

Throughout most of Trump’s tenure, EMD HC spreads tightened except when US growth outpaced EM or when US recession fears took hold. This is testament to our long-held view that EMD HC generally does well when the US economy is neither too hot nor too cold.

Figure 1: Indications from the Trump 1.0 ‘seismometer’

Source: Macrobond, Janus Henderson Investors, 19 December 2024. Past performance does not predict future returns.

2025 scenarios are mostly about US policies

The recent rally in risk assets reflects the expectation of US growth exceeding expectations. Nevertheless, we still expect the EM-US growth differential to trend higher, albeit to a lesser extent than previously anticipated. Similarly, in the context of US monetary policy, a re-pricing has already occurred, with fewer rate cuts now being priced in. Here we consider some scenarios that could impact EMD returns:

- ‘Goldilocks’ is still alive: Steady global growth, US soft landing and contained inflation as Trump policies are watered down or postponed. In this scenario, both the dollar and UST yields are contained and EMD HC spreads remain anchored. Further spread compression would require further improvement in the credit risk of lower-rated sovereigns as spreads are already tight.

This situation mirrors 2017 when Trump first took office. It is most probable, in our view, that the incoming Trump administration focuses first on deregulation, keeps fiscal easing moderate, implements targeted immigration policies, and postpones tariffs for 2026. While US growth forecasts have been revised up following the election, the consensus still sees slower growth next year. - Trade war and “America first”: A front-loaded trade war would negatively surprise markets and lead to wider EMD HC spreads. EM-US growth differentials would be revised down as the US decouples and US inflation would accelerate causing a hawkish re-pricing of US monetary policy (higher rates). However, this scenario could worsen by increased willingness in the US to ease fiscal policy to counter the negative economic impact of a trade war and tighter immigration policies. This environment would lead to a stronger USD, higher UST yields and wider EMD HC spreads. It would further increase the risk of more pronounced concerns about US debt dynamics. To limit the damage in EM, we expect a more significant stimulus response from China to counter tariffs.

- US hard landing and global downturn – Less fiscal easing than expected and tit-for-tat tariffs that escalate into a global trade war could tip the US into recession and drag the global economy down with it. The Fed would have to cut rates more aggressively than anticipated, pushing UST yields lower, but such an environment would surely also push spreads up and equities down in both the US and EMs. This scenario seems less likely as the US economy looks quite resilient and the incoming administration is more likely to pay attention to the economic and inflationary impact of policies.

The difference between the above scenarios mainly relates to the extent, timing, sequencing, and impact of US policies. The latter is likely to play out with a lag, while markets are likely to pay close attention to the first three. We believe that the order in which Trump’s indicated policies are implemented will matter. As discussed, if Trump 1.0 is any guide, economically supportive policies (deregulation and fiscal easing) will be first, followed by economically more costly policies (trade tariffs). Although stricter immigration policy falls into the latter category, we anticipate it as a priority for Trump from the outset; but expect his administration to take a more targeted approach, rather than mass deportations, thus having less of a negative effect on economic activity.

EMD HC remains relatively insulated from Trump 2.0

The impact of Trump’s tariffs is likely to be more country specific and limited for the HC universe given its broader diversity and regional mix and much lower sensitivity to EM currency movements, compared to local currency EM debt. The JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index has less exposure to China (3.7%), Mexico (4.9%), and Emerging Asia ex China (12.4%) than the local currency index (China 10%; Mexico 10%; Asia ex China 35%)3 or EM equity indices where the skew towards Asia is even bigger.

Emerging Asia appears more susceptible to trade restrictions given higher trade volumes to the US. We do not expect universal tariffs and find it much more likely that Trump will have a narrower focus on tariffs to avoid too much self-inflicted damage on the US economy. Hence, China, Mexico and Europe are likely to be the hotbed of the trade war. Europe could well be the weakest link in the global economy in a trade war scenario.

There are several mitigating factors that could insulate EM somewhat from an extreme trade war. Tariffs are likely to lead to EM currency adjustments, shielding some of the direct impact. In China, we expect the policy reaction to include broader stimulus to the domestic economy that is calibrated to the impact from US policies – higher tariffs translating into more stimulus. Policymakers in Beijing have already signalled a strong willingness to act. While everybody loses in the short term from a trade war, over the longer term some countries will emerge as winners as they manage to take advantage of the re-routing of trade in the global economy.

Completion of restructurings signals a more robust EMD HC

With the recent wave of countries exiting restructuring, as discussed in a previous article, this has seen the credit risk of the distressed bucket (CCC and below) improve over 2024. The spreads for this group of countries have enjoyed a remarkable rally, propelled by fundamental improvements. In this bucket, Argentina, El Salvador, Pakistan, Suriname, Ghana, Sri Lanka and Zambia have all seen their rating improve over 2024. Currently, each of these countries is engaged in IMF programmes, except for El Salvador, where an announcement is imminent.

More than half of the high yield (HY) countries in the JPM EMBI GD Index are now in either funded or unfunded IMF programmes4. We believe this suggests an asymmetric risk profile with a significantly reduced risk of ratings downgrades, as commitments to the IMF tend to promote credit-positive policies.

The normalisation of markets in 2024 allowed access to market funding for some of the lower-rated sovereigns in Africa like Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. In 2025, we do not expect any new sovereign defaults and we see further improvement in the capacity of HY countries to access international bond markets. Therefore, we maintain that for active investors, like us, there remains selective value to be captured within the EM HY space.

Overall, the technical backdrop for EMD HC going into 2025 is seen as supportive. While the asset class has seen outflows from dedicated funds, looking at those in isolation understates the demand for the asset class (due to influence of local/domestic investors and crossover investors). Furthermore, while gross sovereign issuance in 2025 is only expected to be slightly lower than last year, net issuance is much smaller, given higher expected maturities and redemptions5. In the HY space, demand for paper is healthy amid limited supply and refinancings.

Return prospects for EMD HC

Given the uncertain macro backdrop, spreads could see some volatility in 2025, but high overall carry provides a buffer. With a positive 2024 taking spreads down to tight levels, further upside is likely to be more country specific. We are therefore focused on identifying those idiosyncratic stories that can ride out the ups and downs of 2025.

Figure 2: 12-month total return estimates for JPM EMBI GD under different scenarios of moves in UST yields and sovereign spreads (% pa.)

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as at 30 November 2024.

Note: Treasury yields are US 10-year yields. For illustrative purposes only. Estimated returns based on annual carry calculation for the representative portfolio, adjusted for potential rates and spread changes. Yields may vary and are subject to change. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised. Past performance does not predict future returns.

The total return heat map (Figure 2) shows that the starting point of higher yield in EMD HC provides a healthy buffer against potential credit spread widening. If markets move sideways, then an investor can still earn the carry – the bold figure in the centre (12-month estimated total return of 6.5%). The inflation shock of 2022 was devastating for fixed income in general, but when combined with a risk-off environment for EMD HC, which dragged spreads wider, this was a double whammy on returns. Going forward, we expect a market environment that is less driven by inflation fears and more by economic growth. Such an environment should see a return of the typical negative correlation between sovereign spreads and UST yields (i.e. they tend to move in opposite directions), helping to stabilise total returns. Furthermore, EMD HC has relatively long duration compared to other higher yielding credit asset classes, which can be beneficial if yields fall further.

Footnotes

1 Source: Macrobond, Bloomberg, 17 December 2024.

2 Source: Janus Henderson, Bloomberg, as at 30 November 2024, using participants of the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index.

3 Source: JP Morgan, as at 30 November 2024.

4 Source: Janus Henderson analysis using IMF data, as at 12 December 2024.

5 Source: JP Morgan, 3 December 2024.