2021: Volatility likely, surprises fewer

-

Steve Cain

Steve Cain

Portfolio Manager -

Aneet Chachra, CFA

Aneet Chachra, CFA

Portfolio Manager -

David Elms

David Elms

Head of Diversified Alternatives | Portfolio Manager

Market GPS |

Market GPS |

2021: Volatility likely, surprises fewer

-

Steve Cain

Steve Cain

Portfolio Manager -

Aneet Chachra, CFA

Aneet Chachra, CFA

Portfolio Manager -

David Elms

David Elms

Head of Diversified Alternatives | Portfolio Manager

The message to take away from 2020 is that the rules are changing. Traditional fiscal and monetary policy has been replaced by exceptional measures to prop up economies and protect jobs in the face of a global pandemic, while increasingly antagonistic relations between countries have ushered in an era of heightened macro and political uncertainty.

Head of Diversified Alternatives David Elms and Diversified Alternatives Portfolio Managers Steve Cain and Aneet Chachra consider the impact of 2020 on investment markets. They explore some of the areas they are looking at as potential risks (and opportunities) for investors as we move into 2021 and explain why they believe that investors should look beyond traditional investment vehicles for real diversification and volatility mitigation.

Key takeaways

- Both implied and realised volatility are likely to remain high as we go through a messy transition to a post-COVID world. However, there are signs that extreme tail outcomes can be avoided.

- Central banks have argued the case for ‘lower for longer’ interest rates. But it is important to consider what history tells us about the risks of excessive stimulus.

- For the past two decades, bonds have provided a natural source of income and diversification for investors. Now could be the time to consider alternative solutions given the environment of the foreseeable future.

The market backdrop coming into 2020 was benign – US stocks at record highs, US unemployment at record lows, and implied volatility measures pinned near lows. Initial news of a virus spreading in China had little impact. Markets were unprepared for a surprise.

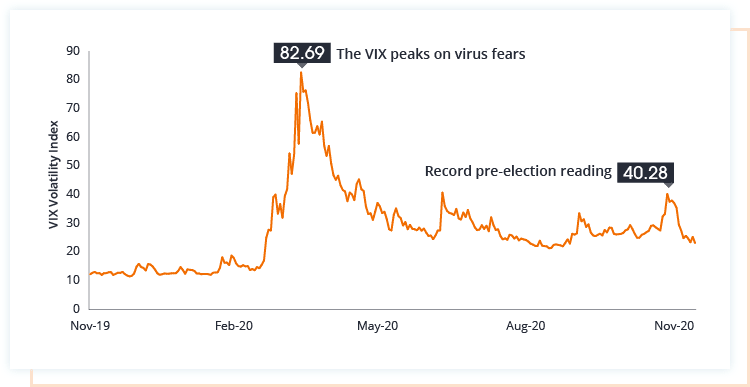

Fast-forward nine months to the US election. It was closely followed around the world and we were barraged with polling data, forecast maps, and opinions on every possible outcome. The equity volatility index (VIX) closed at its highest-ever pre-election reading. Markets were prepared for a surprise. The election result was close in several states and the sitting President hotly disputed the result. In any other year, this would be a constitutional crisis, but in 2020 we have collectively taken the President’s lawsuits and tweets in stride.

Exhibit 1: A benign market backdrop gives way to persistent uncertainty in 2020

Source: Bloomberg, 1 November 2019 to 13 November 2020.

Nevertheless, actual market moves have been objectively quite volatile – the S&P 500® Index posted its largest-ever gain for the day after the US election, followed within days by the largest-ever value versus growth move on Pfizer’s vaccine announcement. But 2020 has already vaccinated us from surprises – short of aliens landing on Earth, it seems there is little that can truly shock us now.

Some caution can be good by making us more anti-fragile. Examples: household savings rates have increased (on average), portfolio leverage has declined, and countries are more resilient to future travel or supply-chain shocks.

We expect both implied and realised volatility to remain high as we go through a messy transition to a post-COVID-19 world. However, there are signs that extreme tail outcomes can be avoided. The US election resulted in political gridlock, nevertheless it seems likely that Congress will quickly agree to new spending if markets fall sharply again. The COVID-19 situation is rapidly worsening across most of the world, but multiple vaccines are on track for 2021.

Hyper-vigilance and anxiety create overreactions, increasing short-term volatility, but also make a complete ‘out of the blue’ shock less likely … 2021 likely brings continued volatility but fewer surprises.”

Hyper-vigilance and anxiety create overreactions, increasing short-term volatility, but also make a complete ‘out of the blue’ shock less likely. From a market perspective, the memory of 2020 will periodically create transient dislocations and opportunities as investors understandably fear getting burned again.

2021 likely brings continued volatility but fewer surprises. Then again, all forecasts for 2020 were useless.

Inflation risk – what if?

A key part of our role as investment managers is to look ahead and scan the world for risk that could materially affect our strategies, but which does not seem appropriately priced into the market’s matrix of cross-asset prices.

Looking to the horizon (whether it be near or far) we observe a material risk for many investors’ portfolios, which we believe is an opportunity for either hedging or risk taking. Namely ‘inflation’.

The arguments for ‘lower for longer’ are well known, and central banks tell us they will manage interest rates to remain low for some time, come what may. But with that backdrop we must pose the question: what if interest rates rise – not a few basis points but a few percent?

But why would they rise?

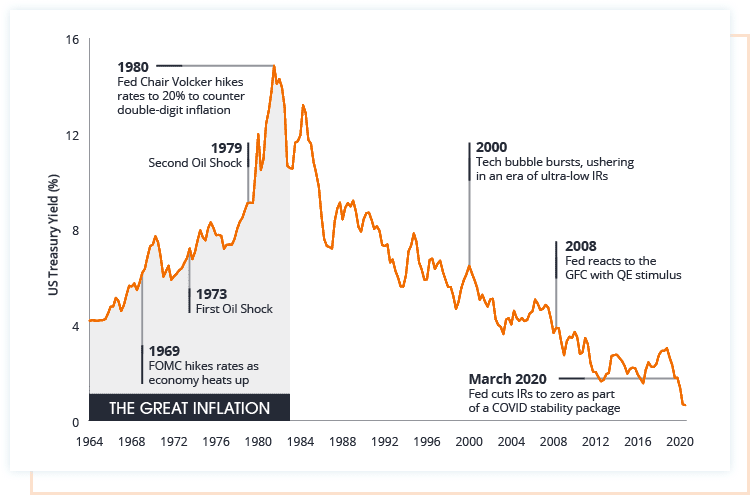

Perhaps history might give us some idea. In 1941, interest rates bottomed – not at the end of the war, but when the US was drawn into the conflict. It is possible to argue that at that point, the market began to price in the war’s resolution. There were huge obstacles ahead, the victory needed to be won, but the market’s perception was that the outcome was set. The subsequent WW2 boom laid the groundwork for the Great Inflation (1965-1982), as illustrated in Exhibit 2, with US interest rates consequently reaching a record high of 20% in March 1980.

Exhibit 2: The post WW2 boom laid the groundwork for the Great Inflation (1965 to 1982)

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Janus Henderson Investors, Global Financial Data, Ind, Federal Reserve Board, Haver Analytics, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, 1 January 1964 to 14 August 2020. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Note: IRs (interest rates), Fed (US Federal Reserve), QE (quantitative easing), FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee), Volcker was head of the US Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987.

Now let us postulate that news on development of a potentially game-changing vaccine was the equivalent of 1941. The fight against COVID-19 is still to be won, we still face the huge logistical challenges that come with manufacture, delivery and inoculation on a global scale, but with a range of potential vaccines under development, the outcome is now clear.

However, we have seen stimulus measures of such scale in 2020 that it may be almost impossible to reverse. This is fiscal policy at levels not unlike the war effort, when countries resorted to printing excessive amounts of money to cover the costs. What happens if we start to price a boom like the post-war years? What happens if the world starts to party like it were 1920 again, following the end of the Spanish flu pandemic? Perhaps then, given the potential risk of over-stimulus, it would be difficult to maintain interest rates as low as they are, for as long as is priced. The party could be short-lived …

We have seen stimulus measures of such scale in 2020 that it may be almost impossible to reverse.”

The risk of this scenario does not seem priced into rates’ volatility, offering an opportunity for hedges that may be attractively priced, given the potential risk of this outcome. If the market cannot see the path, it cannot price in the risk appropriately.

Correlation risk … what if?

For the past two decades, fixed income allocations not only provided income but also outperformed during periods of equity market weakness. Although bond yields have steadily fallen across the world, cutting income, this adverse effect was largely made up by rising hedging benefits. The negative correlation between stocks and bonds can be quite valuable when bond gains offset equity losses during periods of market stress. For example, during the most recent drawdown (19 February to 23 March 2020), US 10-year Treasuries returned +7% as the S&P 500 dropped -34%.

When there is less room for rates to fall, the diversification benefits provided by bonds are reduced.

However, with US yields quite low now, not only is bond income reduced, but upside is capped as well. There is much less room for rates to fall, which reduces diversification potential.

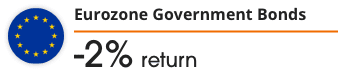

Evidence from Japan and Europe supports this view. Notably, during the same drawdown period above, the Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) Index declined approximately 1% and the Eurozone Government Bonds Index declined 2%. These ‘risk-free’ bonds not only had a negative coupon but also modestly declined in value during the recent market turmoil.

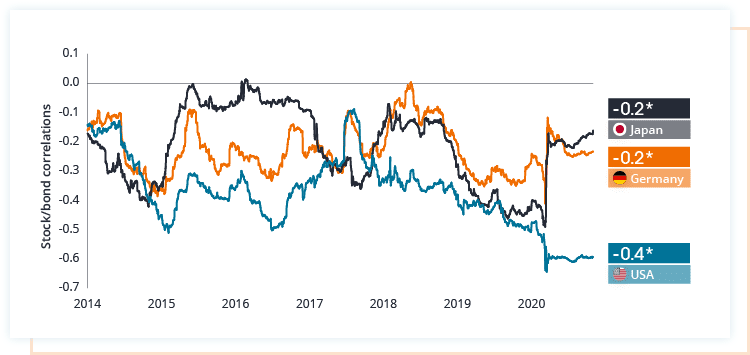

More generally, the diversification benefits provided by bonds are constrained at low yields, while the risk of higher rates or a change in correlation regime increases. Exhibit 3 compares the rolling 1-year daily correlation between stocks/bonds in the US, Japan and Germany, respectively, from January 2014 to October 2020.

Exhibit 3: Are we moving towards a change in correlation regimes?

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 1 January 2014 to 30 October 2020. *Denotes average correlations.

Looking at the chart, you can see US stocks/bonds have been the most negatively correlated, averaging -0.4 versus -0.2 for Japan/Germany. Treasuries have also nearly always been the best diversifier (the blue line is mostly below the others) due to US rates being initially much higher.

With Japanese and German rates now at rock-bottom levels, the potential income and diversification benefits of JGBs and Bunds are limited. US bonds are likely heading down the same path – albeit with low but still positive income and reduced portfolio diversification benefits. Instead of Treasuries mostly being ‘risk-on’ versus ‘risk-off’, price moves will be substantially influenced by financial system liquidity needs, Treasury issuance, US Federal Reserve buybacks, and flows from target-date/balanced funds, etc. We believe that a weakened offsetting relationship between stock and bond price moves may further reduce their appeal as a portfolio hedge.

Finally, investors face the growing risk that stocks and bonds start moving together, as observed through most of the 1990s, leading to potential simultaneous losses. Thus, instead of relying primarily on bonds for portfolio protection, investors may in 2021 consider adding other assets and strategies that are uncorrelated to stocks.

In summary

The past year has seen an evolution of macroeconomic and political risk coupled with risk and risk-free assets rising or falling in concert with government and central bank monetary policy. For 2021, volatility is likely to persist, with the risks outlined above playing their part. This suggests it is prudent for investors to assess the true diversification in their portfolios. This, for some, will mean ensuring some aspect of ‘portfolio protection’ to mitigate the impact of any sustained period of market stress. We may well be more accepting of surprises than this time last year, but equally, the value of being prepared is also hopefully more fully appreciated.

Market GPS Home View All Outlooks