Overall, from what I saw and heard at the COP27 climate summit in Egypt, there were pockets of progress. The discussions included an additional focus on water, youth, loss & damage, food, oceans and forests, which catalysed promising partnerships and climate finance pledges. However, progress is still slow and we are not on a path to limit global warming below 1.5C. We need to change our perception of risk towards climate change – the risk is bigger than what is being priced in. In the global south, opportunities are abundant; we also see prospects for non-renewable energy-related climate mitigation, adaptation and resilience technologies that have not yet reached scale or seen a reduction in risks (unlike solar or wind). We need to move beyond those traditional technologies.

Technology is the science of solving problems and tech’s potential for good was highlighted throughout the conference

Carbon markets are still in their infancy and currently lack quality and credibility; tech can help with promoting their transparency, integrity and usage. Carbon markets were hotly debated at COP27 but not much headway was made. However, it was pleasing to see Japan’s environment ministry launch the Paris Agreement Article 6 Implementation Partnership, which attracted pledges from 40 countries and 23 institutions. Switzerland and Ghana created a landmark agreement focused on efficient lighting and cleaner stoves. Another positive development was the announcement by John Kerry, the US climate envoy, of a new carbon credit programme aimed at mobilising private capital to help middle-income countries transition from coal to renewable energy sources. Meanwhile, at the end of November 2022, the European Commission released a proposal for a new voluntary framework for the certification of carbon removals, which should boost carbon removal technologies and improve the quality of carbon projects.

An introduction to carbon markets

Carbon markets are trading systems where carbon credits are sold and bought. Carbon pricing internalises a previously external cost, facilitating a reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, generating revenue for the new green economy and areas that are underfunded in terms of climate-related finance.

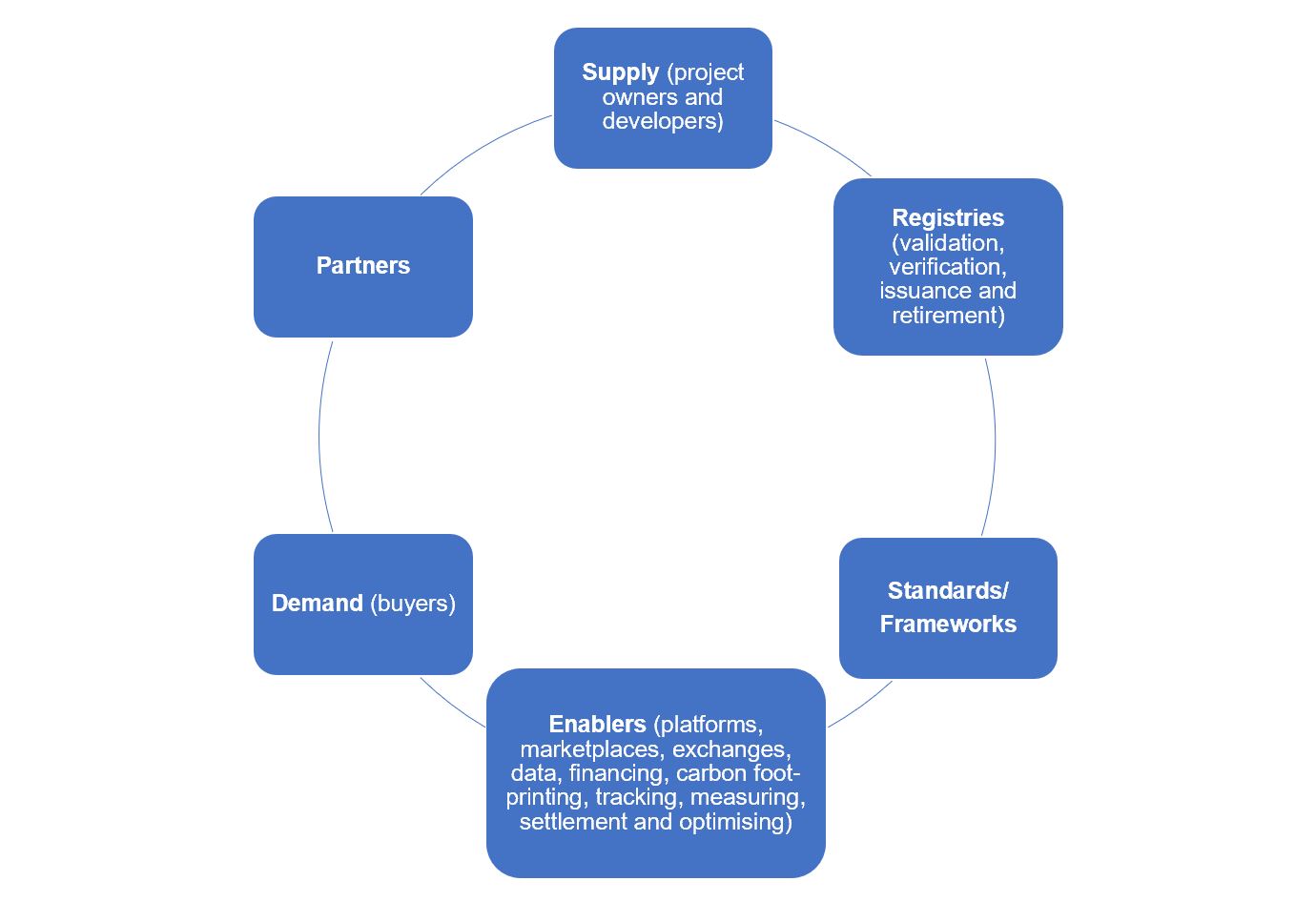

Carbon markets value chain

Source: Janus Henderson Investors.

There are two types of carbon markets:

1) Regulatory/compliance market

The global regulatory/compliance market for carbon credits is huge and growing. According to Refinitiv, the total market size in 2020 was US$261 billion, representing 10.3Gt CO2 equivalent traded.1 Regulatory carbon pricing instruments can take various forms. The most common are emissions trading schemes (ETS), which are essentially cap and trade/pollution permits). There are also emissions reduction funds (taxpayer schemes), carbon taxes, green tax incentives and hybrid approaches.

According to the World Bank, there are over 47 national jurisdictions with some form of initiative, representing more than 20% of global GHG emissions. The quality and pricing of these vary widely from $3.50/tonne CO2e in Mexico (carbon tax), $80/tonne CO2e in the European Union (ETS) to $137/tonne CO2e in Sweden (carbon tax). Academics estimate the real price of GHG emissions to be around $200 tonne CO2e.2

2) Voluntary carbon market

By comparison, the voluntary market is much smaller, fragmented, largely private, with variable standards, and as a result, difficult to measure, with estimates of its value ranging from $400 million to $2 billion per year. Forecasts place the value of the sector between $10-25 billion by 2030 and $90-480bn by 2050.3 The cost of carbon credits varies, particularly for carbon offsets, since the value is linked closely to the perceived quality of the issuing company.

Voluntary credits are purchased by private companies/individuals and do not have to go through the Article 6 system. The current supply of voluntary carbon credits comes from companies, governments, individuals or charities that develop carbon projects. Demand comes from individuals that want to compensate for their carbon footprints, corporations with sustainability targets and net zero strategies, and entities aiming to profit from trading credits. Carbon credits or offsets can either be CO2e reduced; sequestered or avoided, with the latter seen as the least credible.

Carbon markets face multiple challenges

- Real world decarbonisation and the avoidance of double counting: Does the credit create real world decarbonisation, and would that carbon be offset if the credit had not been generated?

- Permanence, and ensuring carbon relevant timelines and calculations: Credits need to be monitored, measured and retired, while GHG emissions should be accurately calculated over time periods and fluctuations, avoiding carbon leakage.

- Verification and quality: We need new skillsets and tools, visibility and expertise. Who will create standardised accounting and perform quality control? Who will enforce, implement grievance mechanisms? Who will be liable and who will enforce adequate social and environmental safeguards?

- Relevance: Ensure carbon offsetting is only utilised for the part of emissions that cannot be abated, not for the easily mitigated sections. For companies to responsibly use carbon credits, they should ideally only help to cover the last 5% to 10% of emissions.

- Scale and diversity of projects

How can technology respond to these challenges?

The following are but a handful of the many ways that tech can support the growth and development of carbon markets:

Blockchain

Enables quick, transparent, inclusive, cheap, safe and efficient transactions, storing important data for carbon credits. This could combat double counting and ensure reliable tracking/measuring, while linking the heterogenous value chain. Blockchain-based platform Veritree (partnering with Samsung) for example offers various nature-based projects.

Tokenisation

The start-up Single.Earth uses a combination of satellite imagery, big data, and machine-learning to map out global carbon models and then converts this analysis to a tokenisation format. This provides local communities with incentives and new revenue streams to maintain ecosystems and provide investors with investment opportunities. GreenToken by SAP utilises tokenisation and blockchain for supply chain carbon management.

Satellite imagery

Enables tracking and monitoring of carbon removal projects in real time, mapping out land or sea, detecting deforestation or illegal fishing. Companies like ICEYE are pioneering in this space with small microwave-size SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) satellites, which are capable of imaging locations at night and through clouds, fog and smoke. Alphabet has lent its satellite imagery, geospatial datasets and machine learning tools to enable deforestation projects to accurately detect troubling sounds, such as chainsaws and vehicles, as well as creating tools like Global Forest Cover Change/Forest Watch, Collect Earth, Earth Engine, Flood Forecasting, and the Map of Life.

Marketplaces

Platforms are needed to connect the global fragmented market, ensuring open, cheap, quick and inclusive participation, enabling participants to interact with ease and confidence. This can help to ensure that carbon projects are of high quality and additional (only going ahead by being enabled by carbon markets), data is stored in a secure manner, and pricing is transparent. Microsoft is launching a carbon and nature credit platform called the Environmental Credit Service. Start-ups like Pledge provide both measurement and analytics tools and an offsetting marketplace of verified nature-based offsets, while Salesforce has its Net Zero Marketplace.

Software, artificial intelligence (AI), simulations, machine learning, data and analytics, carbon accounting, radio-frequency identification (RFID), QR codes, sensors, cameras and drones

A whole range of tools are needed to improve monitoring and reporting, ensure project credibility, reduce the number of site visits and audits, manage projects, enable prototyping, enhance scale, adjust and stabilise project parameters and provide bookkeeping measures.

- Capgemini, ServiceNow, Delta Electronics, Microsoft, S&P Global, SAP and Autodesk are creating tools for their customers to calculate and track carbon projects, report on carbon, as well as creating virtual models.

- Impinj provides RFID solutions, which can enable project inventories.

- Nature Metrics is an innovative new company using eDNA samples taken from biodiversity (from water, invertebrates, faeces, soils, sediments) to analyse the health of ecosystems and provide accurate carbon metrics.

- Ambarella provides energy efficient and AI intelligent chips for areas where lighting is poor or bandwidth is low for cameras. ZeroCO2 has created forest-based carbon offset projects and use QR codes, satellite images, cameras and sensors to track their projects.

Integration

Tools that can integrate offsetting into our everyday lives, ensuring consumers understand the true cost of carbon and can offset emissions directly. Among the payment providers, Adyen is pioneering in this space with their Planet/Restore product.

Tech companies are leading the way

‘Clean tech’ companies are providing offset credits and new decarbonisation pathways. Tesla is actively selling carbon credits to legacy auto manufacturers, while solar microinverters from Enphase Energy or SolarEdge are enhancing solar capabilities and reducing the cost of energy.

Corporate offset buying is growing. Alphabet, Microsoft, and Salesforce have collectively pledged to buy $500 million in carbon removal by 2030. While claims and offset quality may vary, offsets are on the rise and there is a need for carbon credit markets to be ambitious, credible and transparent.

In summary

We view technology as the science of solving problems and key to unlocking the vast potential of carbon markets and the achievement of climate targets. While it remains fragmented and nascent, some interesting investment opportunities are starting to emerge as carbon markets develop further and achieve scale.

1 Gt CO2e = gigatonnes of equivalent carbon dioxide; a simple way to quantify emissions of various greenhouses gases (GHGs) by expressing them in terms of the amount of carbon dioxide that would have the same global warming effect.

2 Source: Annual Review of Resources Economics: Managing Climate Change under Uncertainty: Recursive Integrated Assessment at an Inflection Point.

3 Source: Katusa Research and Trove Intelligence.

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. Its goal is to limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.

Article 6 within the Paris Agreement’s rulebook governing carbon markets allows countries to voluntarily cooperate with each other, meaning they can transfer carbon credits earned from the reduction of GHG emissions to help one or more countries meet their climate targets.

Carbon offsetting allows individuals or organisations to compensate for unavoidable greenhouse gas emissions by supporting projects that reduce, remove or prevent CO2 emissions emitted elsewhere.

Carbon pricing is an instrument that captures the external costs of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – the costs of emissions that the public pays for, such as damage to crops, health care costs from heat waves and droughts, and loss of property from flooding and sea level rise. It ties them to their sources through a price, usually in the form of a price on the carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted.

Net zero refers to cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible to avert the worst impacts of climate change and preserve a liveable planet.

Technology industries can be significantly affected by obsolescence of existing technology, short product cycles, falling prices and profits, competition from new market entrants, and general economic conditions. A concentrated investment in a single industry could be more volatile than the performance of less concentrated investments and the market as a whole.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) or sustainable investing considers factors beyond traditional financial analysis. This may limit available investments and cause performance and exposures to differ from, and potentially be more concentrated in certain areas than, the broader market.

Foreign securities are subject to additional risks including currency fluctuations, political and economic uncertainty, increased volatility, lower liquidity, and differing financial and information reporting standards, all of which are magnified in emerging markets.