Undoubtedly, the benefits of diversification are central to the argument for investing in funds – portfolios of assets – over individual securities, where your metaphorical eggs end up nervously placed in one particular basket. Investing in this way helps mitigate the risks specific to individual companies or sectors and depresses some of the hair-raising volatility of your investments, while still leaving you exposed to the potential for strong long-term returns that a stock market and good portfolio manager can bring.

There is a problem however: there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. Over-diversification can water down the impact of large stock gains, or worse still, leave you paying active fees for a de facto ‘closet tracker’ fund.

John Bennett and Tom O’Hara, portfolio managers of The Henderson European Focus Trust, believe that running a concentrated portfolio is one of the best approaches to building strong long-term returns, but only if stock picking is central to the process and underpinned by rigorous research. Here, we look at why.

Why diversify?

Spreading your investments across a range of stocks and sectors is a tried and tested formula for diversifying away unnecessary risks. It reduces the impact of issues related to one particular company or area of the market, while keeping you exposed to other parts that may be experiencing a solid run.

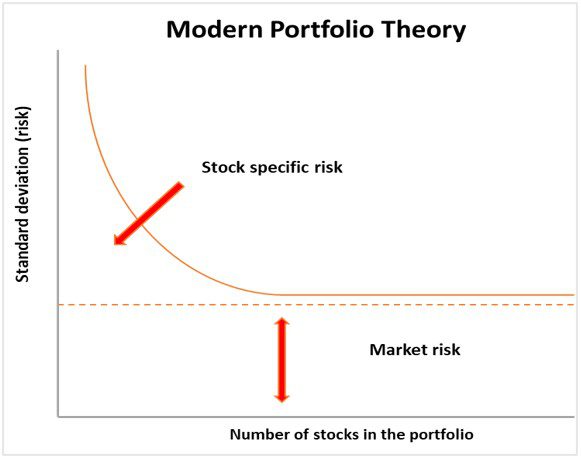

The concept was immortalised in the 1950s by famed economist Harry Markowitz through his work on Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and is the basis for why we invest using collective funds. He theorises that investing in numerous stocks reduces what is called ‘unsystematic’ or stock-specific risks (as shown in the chart below) which refers to issues associated with a specific company like its management team or product. Invest in enough companies, then you can reduce these risks, leaving a portfolio exposed only to ‘systematic’ or market risk – necessary if investors are to receive handsome rewards.

Source: Janus Henderson, as at 20/12/2021

Diversified portfolios seem appropriate given that corporate history is littered with unforeseen events where operational or financial mismanagement or issues with key products or services have proved catastrophic for a firm. Revelations of fraud last year at now defunct German fintech company Wirecard is an excellent example of this. It’s true of sectors too over periods of time. The global pandemic, for example, negatively impacted the travel and leisure sectors. In contrast, the technology sector thrived: many workers adapted to working from home, demand for goods (PC’s and laptops) and services rose, and there is often no need for physical locations when selling and interacting with customers. Each of these scenarios would have been difficult to predict. As such, funds offer investors a diversified portfolio with an active approach to risk management.

Too much of a good thing

While MPT says stock-specific risks are diversified away around 15 stocks1, much debate has been had over this in practice: how many becomes too many?

On one hand, some fund managers believe large stock lists reduce volatility considerably, while still offering investors the potential for solid returns. Some passive trackers have thousands of stocks within them. This approach makes sense if we are to take academic Hendrik Bessembinder’s 2018 work2 at face value, who, after much analysis, found that just 4% of all US stocks since 1926 were responsible for ALL of the wider market’s gains over the period. Indeed, a net cast far and wide might be necessary if we are to catch these paltry numbers of fish.

This argument is not just reserved for passive funds either. There are plenty of strong active managers too who have run long portfolio lists of more than 100 stocks, to great success. This is particularly true with riskier assets, for example, in the small-cap space, where longer lists can give the managers more wiggle-room to invest in companies whose operations have a higher chance of failure but strong upside potential if they get it right.

Yet, on the other hand, plenty of research points to problems with over-diversification. For one, it waters down the impact of stellar performers. Because each and every stock is a minnow in the eyes of the portfolio, a strong run won’t translate into meaningful returns. There’s also the ‘closet tracker’ problem, in which an active fund’s stock list balloons so much it differs little from the index it tracks, yet comparative performance remains considerably weighed down by its active fees.

Warren Buffett, one of the world’s most famous investors, once said: “diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth.” Of course, how concentrated very much comes down to the fund manager’s approach.

Backing high conviction

For Henderson European Focus Trust, the managers and the board believe that the way to generate solid returns and build wealth for shareholders is to run a concentrated portfolio of well-researched, well-valued, high-quality, mid-to-larger sized European businesses. This concentration, they believe, should produce one of the best risk-adjusted returns, giving stellar performers the chance to shine, and was enhanced following the 2020 Annual General Meeting (AGM), when the portfolio’s maximum was reduced from 60 to 45 stocks. In our view, this approach also serves to create a ‘best ideas’ portfolio of the team’s most treasured stock picks. To manage excessive risk taking, the value of any one stock will also not be allowed to exceed 10% of the portfolio.

Essential to this focused approach is the managers’ and team’s skill at stock picking, underpinned by detailed research. Portfolio managers John Bennett and Tom O’Hara focus the portfolio’s philosophy around what they define as their 6 strands of investment ‘DNA’, which outlines the in-depth financial analysis and flexible investment approach that ensures that crucial investment themes are not missed. It also means the team are ready to be wrong and will constantly reassess whether the portfolio is appropriate for the prevailing market cycle. Currently, the Trust is finding opportunities in undervalued parts of the market exposed to the recovery from Covid. These include the classic ‘value’ sectors of autos, banks, and energy.

In keeping with its ‘DNA’, the Trust also places emphasis on companies with a record of generating high and sustainable cash flows, and that employ low levels of leverage in their pursuit of profits. The team want companies that can power their own growth rather than having to rely on debt and the vagaries of market sentiment. They also like finding businesses at an inflexion point – on the precipice of change where cash flow may soon increase dramatically. This could be due to industry shifts, smart capital allocation changes, or the fresh air of new management.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Running a concentrated portfolio of stocks is not for every fund or manager given the high level of conviction that is required to avoid performance missteps. The Trust has outperformed its benchmark3, the MSCI Europe Ex UK over a 3, 5 and 10-year basis. It holds a Silver Analyst rating and 5-stars at Morningstar. In continuing this strong run, the managers will stick to what they know best: running a concentrated portfolio driven by strong stock selection, underpinned by a rigorous research process.

1 Source: Institute of Business and Finance, Articles for Financial Advisers: Risks, January 20162 Source: Hendrik Bessembinder, Do stocks outperform Treasury bills, May 2008

3 Source: Henderson European Focus Trust, Factsheet as at 30/10/2021

Volatility – The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security, or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. It is used as a measure of the riskiness of an investment

Unsystematic or stock specific risk – Unsystematic risk is the risk that is unique to a specific company or industry. It’s also known as non-systematic risk, specific risk, diversifiable risk, or residual risk.

Systematic or market risk – Systematic risk, also known as volatility, non-diversifiable risk, or market risk, is the risk everyone assumes when investing in a market. Think of it as the overall, aggregate risk that comes from things like natural disasters, wars, broad changes in government policies and other events that cannot be planned for or avoided.

Risk-adjusted return – Expressing an investment’s return through how much risk is involved in producing that return. Typical risk measures include alpha, beta, volatility, Sharpe ratio and R2.

Leverage – The use of borrowing to increase exposure to an asset/market. This can be done by borrowing cash and using it to buy an asset, or by using financial instruments such as derivatives to simulate the effect of borrowing for further investment in assets.

Value investing – Value investors search for companies that they believe are undervalued by the market, and therefore expect their share price to increase. One of the favoured techniques is to buy companies with low price to earnings (P/E) ratios.

| Discrete year performance % change (updated quarterly) | Share price | NAV |

|---|---|---|

| 30/09/2020 to 30/09/2021 | 28.8 | 22.6 |

| 30/09/2019 to 30/09/2020 | 3.7 | 5.9 |

| 28/09/2018 to 30/09/2019 | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| 29/09/2017 to 28/09/2018 | -8.6 | 2.0 |

| 30/09/2016 to 30/09/2017 | 36.0 | 21.5 |

All performance, cumulative growth and annual growth data is sourced from Morningstar.