Download White Paper

Download White Paper

Whilst there would be little in the way of debate as to whether ‘COVID-19’ was the most frequently occurring term in 2020 within the world of asset management – or indeed in any context – few would be likely to disagree that ‘ESG’ would have run it a very close second. Indeed, given the meteoric rise in the popularity of ESG-focused investing over recent years, it’s remarkable to reflect on the fact that, as little as a dozen or so years ago, it was a concept that was rarely contemplated, let alone adopted … and, in some quarters, actively eschewed.

This acceleration in interest regarding all things ESG is almost entirely attributable to deepening public interest in matters of societal importance: climate change, sustainability, the environment and conservation, for example. One need only turn on the TV, pick up a newspaper or immerse oneself in a selection of social media platforms for confirmation. Whether it’s Swedish teenage environmental activist Greta Thunberg exhorting her fellow schoolchildren to take part in strikes to promote climate action, Extinction Rebellion protestors bringing London’s traffic to a halt, or the relentless efforts of those such as Sir David Attenborough in TV programmes such as ‘Climate change – the facts’ to alert us to the implications of human behaviour on the natural world, one cannot fail to observe that the tide of sentiment is turning, attitudes are changing, and organisations of all kinds – asset managers included – are responding. Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic may have, albeit temporarily, eclipsed the entreaties of Thunberg, Attenborough and others, it’s nevertheless underlined all too clearly the grave and far-reaching economic damage that can be brought about by the basic mismanagement of environmental issues.

A new element – investing responsibly – is now in the ascendancy therefore, and is assuming considerable importance. The broader history of responsible investing can be traced back to the 18th century, when religious groups such as Quakers and Methodists placed restrictions on the types of company in which their followers could invest. The practice did not emerge in any substantive form until the 1960s however, and was then typically referred to as socially responsible investing (SRI), although other terminology was also in use: social, socially conscious, sustainable, green or ethical investing amongst others. At the time, the approach was relatively simplistic and involved little more than excluding sectors such tobacco, oil and gas, and arms from one’s portfolio. Friends Provident’s Stewardship Fund – the first major ethical fund in the UK marketplace, and the initiative which led the way in terms of focused ethical investment in many people’s eyes – has been around since 1984. A lot has happened in 35 years however, with the space becoming increasingly populated and increasingly complex – for asset managers, advisers, corporations and consumers alike.

Download White Paper

Download White Paper

Turning to ESG itself – the current in vogue idiom – the term was originally coined in 2006 with the launch of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), whose foundations had been laid over the prior two years. Signatories of the PRI, of which one can now count most major professional asset management firms, are bound to follow six principles which demand the incorporation, disclosure and promotion of ESG issues. However, the term didn’t meaningfully enter the vernacular until the arrival of the UN Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 and, as such, catalysed a paradigm shift: establishing the first voluntary link between sustainability and financial services, and preceding other notable landmarks such as the signing of the UN Paris Agreement in 2016 and the European Commission’s Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth in 2018.

Investment flows – the direction of travel

In early April 2019, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) released the fourth edition of its biennial Global Sustainable Investment Review 2018, showing that:

- global sustainable investment assets under management reached over $30 trillion at the start of 2018, a 34% increase from 2016

- responsible investment commands a sizeable share of professionally managed assets regionally, ranging from 18% in Japan to 63% in Australia and New Zealand

- Europe accounts for the largest pool of sustainable investment assets with €12.3 trillion ($14.1 trillion), followed by the US with $12.0 trillion.

Clearly, sustainable investing now constitutes a major force across global financial markets … but in an era where ESG investing has morphed from pipe-dream to mainstream, what exactly is it?

‘ESG’ – what is it?

Historically, the majority of asset management teams, and indeed private investors, would have pursued the shareholder value theory: also known as the ‘Friedman Doctrine’, it was popularised in 1970 by Milton Friedman who advanced the notion that a business’s only social responsibility is the maximisation of shareholder value. Proponents of the doctrine placed the pursuit of profit ahead of all other considerations, and certainly above the pursuit of principles. SRI emerged in the 1960s and ’70s, around the same time as Friedman’s philosophy: whilst some view the Quakers’ earlier exclusion of ‘sinful’ companies as the most significant derivation of this philosophy, others point to South Africa’s apartheid era as the pivotal moment, when investors began divesting from companies that did business there, based on both moral and ethical grounds.

The genesis of the movement was built on a deepening collective recognition that, whilst an absence of profits can bring obvious difficulties of its own, businesses can encounter serious problems if management teams are concerned solely with the fulfilment of profit targets in order to appease shareholders, at the expense of all other stakeholders: employees, customers, suppliers, distributors, the community et al. One need look no further than the well-publicised travails of businesses such as Enron, or more recently Carillion, to grasp how toxic philosophies such as an obsession with short-term profits or a delusional optimism regarding profitability, can rapidly pervade a business’s culture, leading to flawed – and, in some cases, illegal – decision-making which, in turn, serves only to accelerate its demise. In April 2010, the explosion and sinking of the BP-operated Macondo Prospect led to the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the largest marine oil spill in US history. BP bore the brunt of the blame, with pervasive cost-cutting cited as the key contributory factor. Of the 17 S&P 500 companies that went bankrupt between 2005 and 2015, 15 had scored poorly on ESG five years previously.

Given that many of the largest corporate losses have been precipitated by governance failings and fraudulent behaviour, risk management has become a common motivation for ESG. When the movement first emerged, it was primarily driven by a tiny minority of investors who wanted to promote positive social and environmental change – Swedish pension funds were a case in point. What’s really driving the sector’s growth now is a substantial group of executives and financiers who want to avoid harm, whether to their own reputations or to the wider world. Scrutiny of companies is now at a level where decision-makers feel that it is more imprudent to ignore ESG issues than to embrace them. ESG is now no longer simply a campaigning cause; it has become a risk management tool. As ESG considerations move beyond a specialised niche into the mainstream, and investors – both institutions and individuals – increasingly seek to conflate a social conscience with the quest for superior returns, concerns about the risks they are absorbing in order to achieve those returns become paramount. In addition to being appropriate to their objectives and attitudes to risk, there is now a need for asset selections to align with the investor’s ethics, values and moral compass.

Drivers of growth

Three key catalysts have surfaced in recent years in fuelling the ever-widening popularity of ESG investing. These are:

- Regulatory pressure. We have seen a major shift from voluntary measures to binding legislation, which is likely to have a profound impact on driving the transition to a more sustainable model of investing. Governments, needless to say, have been enthusiastic in their embrace of ESG. In the UK for example, one of Theresa May’s final acts before stepping down as prime minister in 2019 was to enshrine in law a commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, making it the first member of the G7 group of industrialised nations to do so. In November, Boris Johnson announced his ‘Ten Point Plan’ to kickstart a green industrial revolution, which will see £12bn of government investment into the net zero target. France also proposed net zero emissions legislation last year, while some smaller countries have targeted dates prior to 2050, such as Finland (2035) and Norway (2030), although the latter allows the buying of carbon offsets. Denmark has very recently become the first major oil producer to stop offering oil and gas exploration licences, ending production by 2050.

- Societal shifts – The public’s awareness of climate change issues has propelled sustainability to the forefront of the global agenda, with society attributing increased levels of importance to sustainable finance and ESG. Interestingly, COVID has accelerated this shift, bringing the real-world implications of neglecting ESG factors sharply into focus, and prompting a particularly strong response from policymakers on the important role that ESG could – and should – play in the measures required to spark global economic recovery. Unsurprisingly, the EU’s 27 heads of state have declared that ‘the green transition’ is central to their post-COVID-19 recovery plan.

- Investor demand – The societal shifts described above have given rise to a new cohort of investors motivated as much, if not more so, by non-financial impacts as by financial returns. Of these, institutional investors form the largest component, not least as they are compelled to react to mounting pressure from policymakers and their wider universe of stakeholders to incorporate sustainability more intrinsically into their mandates. In response, asset managers are – as we’ve seen – increasingly incorporating ESG standards into their offerings: either developing new vehicles with sustainable mandates or repurposing existing vehicles.

… and how does it work?

Whilst the approach is relatively easy to describe in the abstract, it is harder to do so definitively and, therefore, difficult to implement authoritatively. At its simplest, it involves the use of exclusionary screens, or filters, that investors can deploy to eliminate ESG transgressors from the traditional investment universe, ie businesses deriving some or all of their earnings from one or more of the traditional ‘sin’ industries – animal testing, fur, gambling, pornography, tobacco or weapons – or those which have a particularly poor record in terms of human rights or corruption. This is commonly referred to as ‘negative screening’. The alternative approach – ‘positive screening’ – seeks to invest in companies which are actively making a positive contribution to a range of ESG themes, such as improvements in energy efficiency, affordable healthcare or micro-finance (and other forms of financial inclusion). However, one should note the distinction between an ethical, responsible or impact-driven investment process, and an ESG integrated process. Specific ethical, responsible or impact-driven processes will often define the objective of an investment vehicle such that the investment process is built entirely around the philosophical belief of the client or manager. ESG investing, on the other hand, is far more flexible, and represents the integration of material ESG risk factors into an enduring investment process.

Returning to the subject of negative screening, the logic for the exclusion of businesses indulging in activities such as alcohol, fossil fuels, nuclear power, food and drink or technology is more debatable. For example, BP is going ahead with a shareholder resolution in support of its goal of net zero emissions by 2050, a goal previously declared by Shell which is also diversifying its product line-up by entering the electric vehicle market. In the food and drink sector, concerns over the health effects of excessive sugar consumption are resulting in shifting consumer preferences, regulation and litigation, with soft drink companies trying to address the risk through reduced-calorie products and marketing restrictions. The industry is also under increased scrutiny for using its influence to mislead the public about sugar-related health risks, although Danone and Nestlé lead the way in terms of sound corporate behaviour because of their disclosure of relatively robust product health, marketing and political involvement policy commitments.

Moving on to technology, it is a sector which naturally screens well for ESG in that its constituents tend to have a small carbon footprint as well as younger and more diverse workforces. However, firms like Alphabet (which owns Google and YouTube), Facebook (which owns Instagram and WhatsApp) and Microsoft have consolidated market power to the point that anti-competitive concerns have emerged, raising the possibility that these tech giants could face anti-trust litigation and eventually be broken up. Moreover, the collection of massive amounts of consumer data, which are then leveraged for advertising and sales revenue, not only creates significant competitive advantages but also raises issues surrounding privacy and concern over the spread of disinformation. Regulators, particularly the European Commission, are beginning to question whether the concentration of power in technology companies is beneficial for consumers over the long run. More positively, while Alphabet became embroiled in an anti-trust law suit in October of last year, it did become carbon neutral in 2007 and became the first company of its size to use renewable energy to counteract its entire output.

The issues are far from binary therefore – not least as there are no absolutes as to what constitutes morality – and, as a result, ESG investment remains somewhat subjective in nature. Given the lack of any consensus as to what constitutes ‘good’ corporate behaviour consistent with ESG principles, available definitions are invariably based on value judgements, and there exists no standard reporting framework. Moreover, asset managers are obliged to rely heavily on ESG ratings providers – the likes of MSCI, FTSE Russell and Sustainalytics are amongst the most prominent – in the process of stock selection, whose proprietary scoring methods often yield radically different assessments of the same business.

Interestingly – or perhaps worryingly – a study published by Research Affiliates, a US-based global leader in asset allocation, in January last year compared the performance of two portfolios, one in Europe and one in the US, each constructed based on the ratings of two well-known ESG ratings providers. The portfolios yielded large performance dispersion and low correlation of returns: over the eight-year period for which ratings data was available from both providers – July 2010 to June 2018 – the European portfolios had a performance dispersion of 70 basis points a year (9.4% versus 8.7%) and 130 bps a year in the US (14.2% versus 12.9%), which translates into a cumulative performance difference of 10.0% and 24.1% respectively over the full period!3 This represents a noticeable difference for two strategies with an identical portfolio construction process.

The study also examined 20 of the largest US corporations by market capitalisation in terms of their overall ESG rating and individual environmental, social and governance ratings from the two ratings providers, and found an abundance of anomalies. For example, ratings provider 1 ranked Wells Fargo in the top third by governance in their universe, whereas provider 2 ranked it in the bottom 5%. This data was collected in 2017 when Wells Fargo was in the middle of its very public fake account scandal. Similarly, provider 1 scored Facebook in the top quartile on environmental criteria whilst provider 2 scored it in the bottom quartile.3 MSCI ranks Tesla at the top of the automotive ESG table; FTSE Russell regards it as the worst carmaker globally based on ESG criteria.

Does a focus on ESG lead to outperformance?

There is now a substantial body of empirical analysis dispelling the long-held view that, by investing sustainably, investors are foregoing the potential for outperformance; indeed, there is burgeoning evidence that suggests a strong synergy between the two, supporting the view that a company’s focus on sustainability is fundamentally indicative of its board and management quality.

| Sector | Average return of ESG funds | Average return of non-ESG funds | Outperformance of ESG funds |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA North America | 26.7% | 8.7% | 18.0% |

| IA Flexible Investment | 7.0% | -1.8% | 8.8% |

| IA Mixed Investment 40-85% Shares | 5.3% | -2.3% | 7.6% |

| IA UK Direct Property | 2.4% | -4.2% | 6.6% |

| IA Volatility Managed | 4.2% | -2.3% | 6.5% |

| IA Global | 10.1% | 4.1% | 6.0% |

| IA Global Equity Income | 0.8% | -5.1% | 5.9% |

| IA Mixed Investment 0-35% Shares | 5.3% | -0.3% | 5.6% |

| IA Europe excluding UK | 5.6% | 0.0% | 5.6% |

| IA Mixed Investment 20-60% Shares | 1.6% | -2.5% | 4.1% |

| IA Sterling High Yield | 2.0% | -1.8% | 3.7% |

| IA Targeted Absolute Return | 2.8% | -0.2% | 3.0% |

| IA UK Equity Income | -18.1% | -21.2% | 3.0% |

| IA UK All Companies | -14.5% | -17.3% | 2.9% |

| IA Property Other | -9.7% | -12.0% | 2.3% |

| IA Global Emerging Markets | 0.3% | -1.2% | 1.5% |

| IA UK Smaller Companies | -8.9% | -10.3% | 1.4% |

| IA Sterling Strategic Boards | 3.0% | 2.1% | 0.9% |

| IA Specialist | -2.2% | -2.8% | 0.6% |

| IA Short Term Money Market | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| IA Unclassified | -1.1% | -1.2% | 0.1% |

| IA Global Bonds | 3.4% | 3.5% | -0.1% |

| IA Asia Pacific excluding Japan | 4.9% | 5.3% | -0.4% |

| IA Sterling Corporate Bond | 2.9% | 3.6% | -0.7% |

| IA Japan | -3.3% | -1.2% | -2.0% |

| IA Asia Pacific including Japan | 7.2% | 11.7% | -4.6% |

| IA Europe including UK | -7.6% | -0.4% | -7.1% |

Henderson EuroTrust, a Europe (ex-UK) investment trust focusing on high quality, mid to large cap equities, has consistently ranked as one of the leading trusts on Morningstar’s sustainability rankings. Its portfolio manager, Jamie Ross, has been an enthusiastic advocate of ESG as an integrated stock selection methodology, his investment process being so focussed on governance and sustainability that it naturally aligns with ESG. It’s an approach which continues to bear fruit with the trust’s share price and net asset value both well ahead of the benchmark over one, three, five and 10 years on a total return basis.7 Ross cites the fact that the words and actions of the EU and member state governments – the formalisation in 2019 of Europe’s approach to sustainability via ‘The European Green Deal’, followed by the presentation of the 2030 Climate Target Plan in September of last year – have fed down to individual European businesses as the key phenomenon driving the focus regionally, to the extent that companies are now considerably more concerned about sustainability. This heightened interest manifests itself in a number of ways, from the long-term incentivisation of management teams to radical shifts in business strategy.

Holdings within the trust playing to the sustainability theme include plasma drug maker Grifols, Dutch health nutrition provider DSM, Danish pharmaceutical specialist Novo Nordisk which has been at the cutting edge of diabetes care for almost 100 years and SIG Combibloc, the Swiss packaging company which, via its aseptic packaging, provides an environmentally friendly alternative to plastic. According to Ross, it is no coincidence that seven of the world’s 10 largest renewable energy companies by installed capacity are European. Given that ESG criteria are increasingly being deployed as risk management metrics, and that strong performers are likely to see a marked reduction in their cost of capital – a competitive advantage which would naturally lead to an increase in equity value – he views European companies as likely to benefit disproportionately from the current trend.

From an ESG perspective, Ollie regards the trust as well-placed, and sees significant potential at the small cap end of the market which is well-populated with pureplay sustainable development goal businesses – in particular those focused on energy transition – still available at very attractive valuation multiples. Amongst those which are emblematic of ESG adoption within the portfolio, he cites companies such as Nordex, makers of wind turbines, Nexans, manufacturers of the high voltage cabling that links wind turbines to the national grid, and SMA, which makes solar inverters.

What now?

Investors are becoming increasingly aware of environmental, social and governance challenges around the world and the fundamental role that corporations can play in improving, or worsening, these issues … and genuine awareness is leading to genuine action. Moreover, investors also now have ample data to support the view that adopting an ESG approach does not necessarily mean resigning oneself to inferior performance, based on the largely undeniable logic that companies which demonstrate their awareness of, and adherence to, ESG principles are more likely to have superior standards of governance which, in turn, should translate into improved resilience in challenging economic conditions. As demand increases, so too will the range of investment solutions on offer.

In short, therefore, with sustainability issues now being prioritised at the highest governmental and corporate levels, the rise of ESG investing is set to continue; companies will undoubtedly be subjected to an increasing set of non-financial reporting requirements – such as disclosing their ESG impact – which will in all likelihood adversely affect the ability of poorer performers to raise capital.

Based on current trends, we anticipate that the use of ESG metrics will represent another key item in the toolkit used by asset managers to evaluate investments, alongside valuation ratios, earnings growth and balance sheet strength, among others. Portfolios which aren’t aimed at dedicated sustainable investors may also benefit from any ESG tailwinds therefore. As ESG investment processes become more sophisticated and the increasing impact and social acknowledgment of sustainability risks further shift investor sentiment in favour of ESG investments, it is hard to see how ESG considerations will not be incorporated into all of our investment decisions at some point in the future.

Last year, Charlie Munger – Warren Buffett’s long-time business partner at Berkshire Hathaway – expressed his opinion that all investing is value investing. It remains to be seen whether he will soon be advancing the view that all investing is ESG investing.

Download White Paper

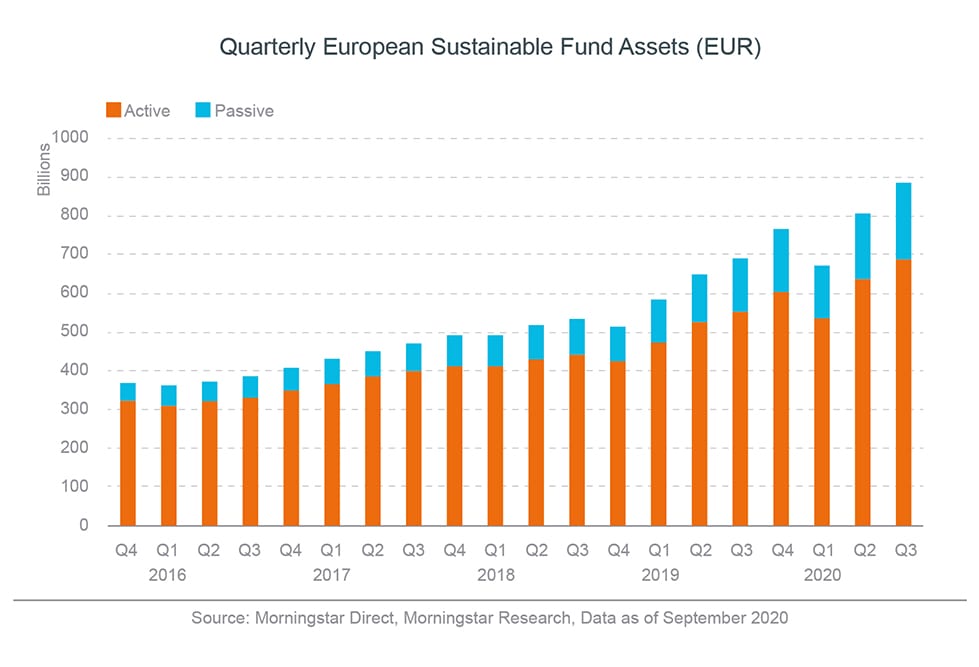

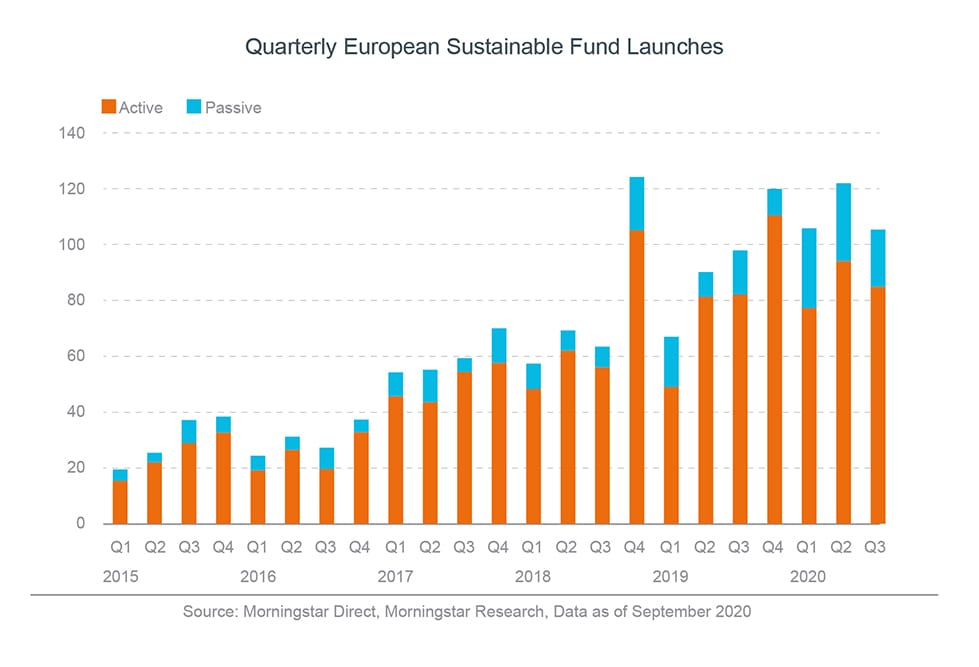

1 Morningstar, as at 30.09.20

2 PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2022 – The growth opportunity of the century, November 2020

3 Research Affiliates, LLC, What a difference an ESG ratings provider makes!, January 2020

4 Bloomberg, as at 13.03.20

5 Source: FE Analytics, 31.12.19 to 31.08.20, data from FEfundinfo2020

6 https://www.ft.com/content/733ee6ff-446e-4f8b-86b2-19ef42da3824

7 Source: Morningstar, to 30.11.20