Longer-maturity U.S. government bond yields have been slowly rising since early August 2020, when the 10-year Treasury hit a record low of 0.51%. But on 6 January 2021,1 the day after the Georgia special election appeared poised to hand control of the Senate to Democrats, the yield spiked above 1%. Just three days later, it hit a new post-crisis high of 1.15%. Do we expect a trend toward rapidly higher yields from here? In a word, no. However, the balance of risks suggests higher government bond yields are still more likely than lower ones in the quarters ahead.

Democratic control of both the legislative and executive branches suggests greater economic stimulus is likely. The most recent headlines – which are always just a starting point – report President Biden is seeking another relief package of nearly $2 trillion, almost 10% of U.S. GDP2. Since more stimulus is intended to spur more economic growth, it increases the chances of a more normal economic environment and thus more normal levels of interest rates. But it will take time and is not without risks.

A full recovery of the U.S. economy depends on a successful global effort to vaccinate the world’s population from an evolving virus – by no means a straightforward process. Even after the vaccination effort is complete and herd immunity is reached, it will take time to reduce the slack in the economy. Unemployment is elevated, allowing significant growth before the economy is at risk of overheating.

Finally, the Fed has already lowered interest rates to zero while funding unprecedented quantitative easing (the direct purchases of bonds). With reduced options to stimulate the economy further, if needed, they are more likely to err on the side of caution, delaying interest rate hikes until they are certain the recovery is here to stay.

Are historical yields a good indicator of future yields?

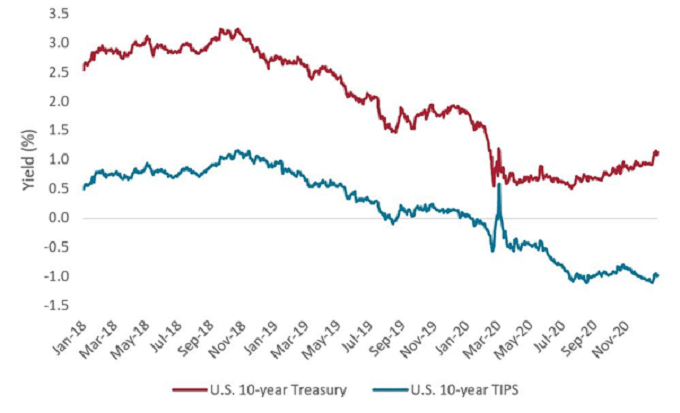

We believe current yields are fundamentally too low for the level of economic activity today, never mind what is expected in the next year or two. Exhibit 1 shows the path of recent 10-year bond yields, as well as the yield from 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), which illustrates a ‘real’ yield – the yield realized after taking expected inflation into account. Before the crisis, 10-year yields ranged from 1.5% to 2.0%, well above current levels; just a year before that, they were closer to 3.0%. Real 10-year yields have been negative for over two years and spent the bulk of 2020 at near -1%. Normalizing economic activity should lead to more normalization in interest rates. As a result, 1.5% – the level 10-year bonds traded on 31 January, just before the U.S. declared COVID-19 a public health emergency – could well be touched this year.

Positioning for a higher-rate world

In the meantime, we – and the market – expect the Fed to keep a firm lid on short-term rates and their thumb on longer-term rates, buying as needed to prevent a sharp rise in rates that could disrupt the economic recovery. Thus, we have a bit of a conundrum: rates are ‘too low’ and the market agrees the Fed is unlikely to raise them soon, and yet the market is pushing longer-maturity yields higher. But maybe this is exactly what the Fed wants – slow, tenuous rise in longer-dated bonds. This would effectively be a Goldilocks scenario for the zero-rate, post-COVID era: not too hot to threaten the recovery, and not too cool to require an (inevitable) sudden and dramatic rise in rates down the road.

Keep in mind that the stock market has adjusted to the improved expectations for economic growth in recent months, while the bond market has been more subdued. Perhaps slowly closing the gap between what is priced into the stock and bond markets is in the Fed’s interest and would ultimately be better – like the right temperature of porridge – for long-term sustained economic growth.

While bonds have been and are likely to remain in demand by investors seeking yield or diversification from equities (or both), it looks increasingly likely that we have seen the low point in yields for the current cycle. As higher yields will be more prominent at the longer end of the curve, given the stability of policy rates at the short end, we encourage investors to consider how much interest rate risk they have in their portfolios and make sure it is appropriate for their needs.

Rising rates can be a headwind for a bond portfolio but finding the right balance of interest rate risk and diversification is key as the path toward higher rates is likely to fluctuate. Unexpected geopolitical, economic or virus-related events could see equities falter and interest rates decline again, boosting bond returns. Furthermore, as markets are prone to being overbought and oversold around a trend, tactical adjustments in interest rate exposure could prove to be as valuable as strategic positions. While the trend may be toward higher interest rates, surprises will inevitably appear, and circumstances will change. As such, we believe investors should remain active, when considering positioning their portfolios for higher yields, by recognizing volatility around a trend as an opportunity to dynamically adjust risk and add value.

12021

2US Gross Domestic Product, in current dollars, for 2019 was $21.433 trillion. Source: World Bank.