It must be frustrating being a political incumbent. All that government spending of the last few years and the electorate sees fit to eject you from power. In the UK, the Conservatives lost heavily to Labour, France’s ruling Macron group shed assembly seats, while in the US, Biden/Harris trail Trump according to the latest polls.

Where is the thanks for the expenditure on COVID or the boost to domestic manufacturing from various infrastructure and subsidy initiatives? Perhaps the electorate is simply too canny and wise to some of the repercussions of this expansion of government debt. For one, it arguably brought forward economic growth as well as contributing to higher inflation when supply chains were under pressure.

Just as higher inflation is no friend to bonds – it pushes up bond yields causing bond prices to fall – it is similarly toxic in politics. Not least because it fuels inequality, acting as a tax on the poor, and spurring populism. Households felt the pinch as inflation soared, eating into the value of what their money could buy. The good news is that supply chain pressures have eased as post-pandemic trade has normalised. Meanwhile, central banks’ efforts to dampen the economy by raising interest rates and shrinking their balance sheets is now bearing fruit as inflation moderates.

A swift retreat

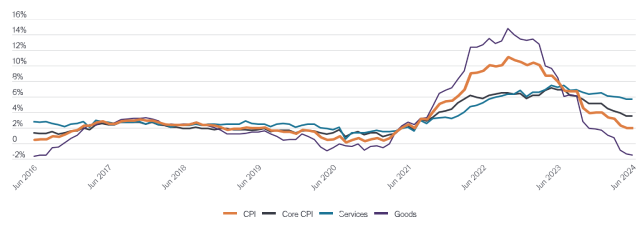

The chart shows how inflation in the UK has come down swiftly this year. In fact, it is already back to the Bank of England’s target of 2%.

We said a year ago that time lags in data and pricing decisions at companies (which had tactically taken advantage of inflation to hike prices at once) had likely elevated inflation and some patience was needed for the tide to turn. It is therefore encouraging to see this rapid drop in headline inflation.

Headline year-on-year CPI inflation steadied at 2% in June after the same figure in May. It might have been lower had it not been for some curiously high accommodation services figures. Taylor Swift, the pop star, may be to blame. She is fast turning into the new weather phenomenon – at a stroke responsible for upticks in economic growth or inflation. To be fair, when some hotels are hiking their prices as much as 100% in a month on the days when her sell-out UK tour is in town, it will feed into inflation figures.

The flipside of government spending and higher inflation is that the money goes somewhere. Companies have experienced strong nominal growth in their revenues after putting up prices. Higher earnings means leverage (net debt/earnings) ratios have fallen over the last couple of years, albeit with a mild uptick recently.1 We have seen this translate into a fairly low default rate. By that we mean the proportion of bond issuers not meeting their repayments to bondholders. In the past 12 months, the default rate among sub-investment grade (or high yield) bond issuers was 3.9%2, a fairly modest spike given that hikes in interest rates typically cause more pain.

Are there other factors at work that could have supported corporates? One may be the development of a growing private credit market. This is where companies seek to borrow directly from private non-bank lenders rather than issuing debt in the form of bonds that are publicly traded. The advantage to the corporate borrower is that they might be able to get more favourable lending terms and rates. This extra competition might depress yields on publicly traded bonds but additional sources of funding for companies, particularly at a time when banks had been tightening their credit standards, could be helping to suppress default rates.

UK Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation

Source: LSEG Datastream, UK Office for National Statistics.

Note: Core CPI excludes food, energy and tobacco prices. 30 June 2016 to 30 June 2024.

Direction of travel

The first half of 2024 marked a turning point for developed market monetary policy as central banks in Switzerland, Sweden, Canada and the Eurozone moved to cut rates. The Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve have yet to join that group but markets expect cuts before the year end. We were among those who had expected cuts to happen earlier and were surprised at the lag between higher interest rates and its impact on slowing the economy, especially in the US, where high government spending, a longer process of exhausting savings built up during COVID, and high immigration and artificial intelligence boosting productivity, had kept growth higher for longer than expected. Economic moderation in the US suggests we are finally moving beyond the macro purgatory.

We expect the move to lower rates to be helpful for bond markets, bringing down the yields on government bonds (and lifting bond prices), while taking some of the pressure off rising refinancing costs among corporate borrowers.

That does not mean we can be carefree about which bonds to own. The hallmark of the last couple of years has been lags between cause and effect. Just because interest rates are falling, it does not mean companies are able to replace their existing debt at lower rates. They may still be facing a step-up from the rates at which they borrowed a few years ago, just as many mortgage borrowers coming off five-year fixed terms are discovering.

For this reason, it remains important to do our homework, lending to borrowers that we believe have the quality of earnings to cover their obligations to bondholders. For government borrowers, the Liz Truss debacle demonstrated a market that can quickly punish profligacy, so we reckon populist increased spending measures are likely to get reined in. If economies need a boost, it may once again fall to central banks to help out through looser monetary policy because governments have already raided the piggy bank.

Footnotes

1Source: JPMorgan, Net debt = Borrowings less cash/earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation, at end Q1 2024 for US and European investment grade and high yield corporate bond markets.

2Source: S&P Global Ratings, 31 March 2024.

Corporate bonds: Bonds issued by companies. These can be rated investment grade by credit rating agencies, which means they are perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting (failing to meet repayments to bondholders). Conversely, bonds rated high yield carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in an economy.

Monetary policy: Policies of a central bank aimed at influencing inflation and growth in an economy through setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Looser policy is when they cut rates to stimulate the economy.

Yield: The level of income on a bond over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate.