Market review

As the global monetary policy easing cycle broadened, yields moved lower across the curve. The Australian bond market, as measured by the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index, rose 1.21%.

As the global monetary policy easing cycle broadened, yields moved lower across the curve.

Australia’s three-year government bond yields ended the month 20 basis points (bps) lower at 3.55%, while 10-year government bond yields were 15bps lower at 3.97%. Against the current cash target rate of 4.35%, three-month bank bills ended 10bps lower at 4.39%. Six-month bank bill yields ended 26bps lower at 4.53%. The Australian yield curve continued to steepen, as further Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) rate cuts were priced across the next year.

The RBA kept interest rates on hold, at 4.35%, and warned of elevated inflation risks. They chose to keep rates unchanged due to the uncertainty around financial market volatility, but noted any further upside inflation surprises would not be tolerated. Meanwhile, headline employment data showed some strength. Offsetting this is the continued rise in unemployment as labour supply is rising faster than labour demand. Wages growth has also turned lower, with private sector wages growth coming in below the peak, at 4% year-on-year for quarter two (Q2) 2024, which is the lowest quarterly growth rate since 2021. Households remain cautious and appear to be saving their tax cuts more than spending, at this stage. Retail sales and the new Household Spending Indicator were flat to lower in the month.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand and Sweden’s Riksbank joined their G10 peers in easing in August. Six of the ten major developed economies have now lowered their monetary policy rate. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Powell, noted at the annual Jackson Hole conference that the Fed would be easing at their September meeting. This is a powerful signal that broad global economic conditions are softening, and that there are growing downside pressures. The Chinese economy is also slowing, and their central bank also lowered the policy rate in August. While there is little immediate local impact, these conditions will influence the environment that Australia operates in over the coming year.

Market outlook

The Australian economy is slowing, and while no recession is forecast, the pressure of higher interest rates is broadening out across sectors of the economy. Inflation is moderating slowly from high levels. The RBA needs to balance these risks along their so-called narrow path. An extended period of policy at restrictive levels will slow growth further, rebalance the labour market and subdue inflation. The global economic backdrop is slowing, and while there remain volatility risks, the policy path is lower.

Our base case is for the RBA to remain on hold at current rates before commencing an easing cycle in Q1 2025. We price a more modest than the historically average easing cycle, of around 175bps, spread over an extended period. There remain a myriad of risks to the base case, with the high case of a late cycle hike in H2 2024, and a slow cycle easing through to 2026. We hold an alternate case of an earlier commencement, which finishes with more easing over the whole cycle. This is equally possible as the high case, under the current environment. The market has built in an RBA easing cycle, with around 130bps priced over two years. We believe there is value in targeted parts of the curve which outperform into easing cycles. We continue to hold a long duration position.

Monthly focus – Are insolvencies a risk?

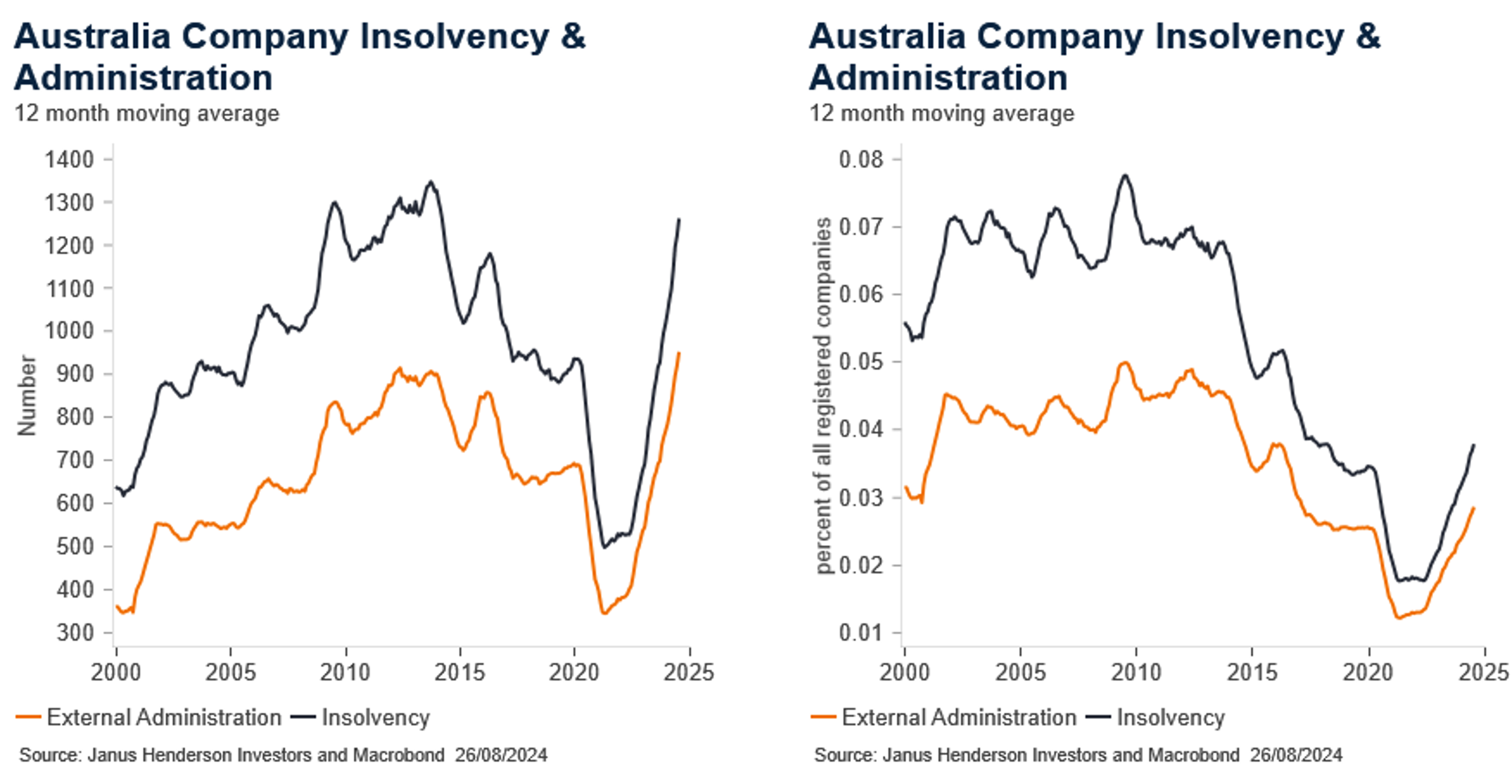

We, as well as the RBA, have been monitoring the rapid rise in company insolvencies and bankruptcies reported by Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). In July, 1,231 companies entered external administration, close to the record high of 1,249 seen in May 2024, with the ASIC data starting in 1999. There have been 11,429 insolvencies in the 12 months to August 2024, also a record high for annual data.

The outright number of insolvencies is concerning and has made for some alarming headlines. The question we need to answer is if it is part of a post pandemic, normalisation of cyclical patterns, or indicative of further declining domestic demand? The pandemic period saw a period of significantly below average numbers of insolvencies, due to moratoriums and broad fiscal support. The current rise may be partly due to a normalisation after the extended period of below average insolvencies, rather than solely due to an outright loss of demand in the economy.

The difference between current and average insolvencies indicates that there has indeed been a significant difference from long-term norms, and a build-up in potential insolvencies. Examining the number of insolvencies as a percent of all registered companies shows a much lower level of concern regarding the current number than outright levels. The proportions remain low, albeit rising, and there is some way to go before there is a full normalisation of insolvencies as a ratio of all registered companies. Given this, we can expect the numbers to continue rising over the year ahead, as further normalisation occurs amid a broader economic slowdown. In itself this should not be a prudential concern for the RBA, but the speed of adjustment will continue to warrant close monitoring.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) report that in 2022-23, 91.9% of Australian actively trading businesses had a turnover size of less than $2 million. If we assume a normal distribution, we can imply that many of the insolvent companies operate in the small and medium sized enterprise space.1 The recent count of Australian businesses showed that there was a net decline in the number of small businesses which hired less than 5 employees, a flat outcome for those employing 5-19 employees, and a nearly 6% increase in larger businesses. Additionally, the ABS report that 51% of all Australian jobs are in small and medium sized businesses, i.e., with less than 200 employees.2

The loss of any business is likely to lead to lower labour demand, and so it should be expected that there will be an impact on the labour market. With the sector facing the greatest pressures, hiring around half the workforce, it should have only a modest softening on demand in the overall workforce. This should be enough to bring labour demand and supply into greater balance, and moderate wage growth; but on current numbers it is not large enough to generate widespread, aggregate job shedding. Our forecast remains for a steady rise in the unemployment rate over the coming year.

Views as at 31 August 2024.

1Australian Bureau of Statistics, “Counts of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits,” 22/8/2023

2Australian Bureau of Statistics, “Jobs in Australia,” 6/12/2023