This year’s World Bank and IMF Annual Meetings took place in Marrakech, Morocco, from 9 October to 15 October, and, as always, it was a huge affair, attended by some 14,000 delegates.1 Besides the main official schedule, there were many side events organised by large investment banks covering Emerging Markets (EM), panel discussions, seminars, and small group meetings. This “must-attend” event for anyone involved in EM investing provided us with a great opportunity, inter alia, to join the debate around some of the most pressing global issues as well as meet with a wide range of country delegations in a short space of time.

It was only the second time in history that this event had been held in Africa and it was meant to showcase the focus of multilateral institutions on global challenges affecting Africa (of which climate and debt stand out) as well as demonstrating Morocco’s ability to organise a massive international event and to promote its image as an open, dynamic and successful emerging market.2

In the end, it did all of that, and then some: the organisation of the event went off without a hitch, especially given the fact that only a few weeks before the region around Marrakech had been hit by a devastating earthquake that killed nearly 3,000 people and caused billions of dollars’ worth of damage.3

A bird’s eye view on the global landscape for EM

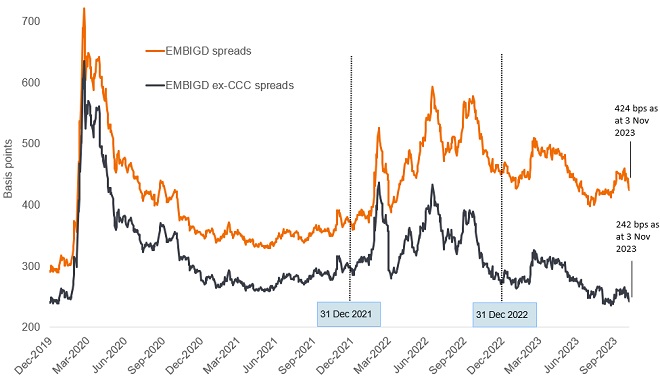

A key word that we kept hearing was “resilience”. This was not only in relation to the US economy’s surprising strength, but also large EMs (ex-China, where we are witnessing a structural slowdown). EM assets have certainly held up well in the face of global macro headwinds (higher developed market yields, tighter financial conditions and slowing global growth). In the EM debt hard currency asset class, as represented by the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified (EMBIGD), headline spreads have actually tightened year-to-date (as of 3 November 2023), despite relentless fund outflows (see Figure 1).4 Excluding CCC-rated issues, spreads have actually tightened to pre-Covid levels.

Figure 1: EM hard currency spreads have proved resilient in 2023

Source: Janus Henderson, Bloomberg and JP Morgan. Data is as at 3 November 2023. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

That said, there were also widely expressed concerns around debt sustainability among high yield EM issuers in a “higher-for-longer” rate scenario in developed markets. Although inflation has peaked in the developed world, targets of 2% are still a long way away and during the third quarter of 2023 we saw a reset in policy rate expectations driving a staggering rise in real yields. The higher-for-longer scenario is worrying because it constrains the available fiscal space, making structural reforms harder to implement.

A third key takeaway is the palpable resurgence of geopolitical risk (with conflicts raging in the Middle East and Ukraine) and the escalating geoeconomic fragmentation. Next year’s US elections may turbocharge these two trends and cause gyrations in the markets, a scenario that is not yet reflected in valuations. Shifting global alliances, it was noted, were also creating winners and losers. Among those identified as winners were Mexico and India, but also smaller countries like our host, Morocco.

Key messages from the IMF

During the event, on October 10th, the IMF released its latest World Economic Outlook (WEO). Among the positive messages, the IMF highlighted that fears of widespread recession among the world’s leading economies were slowly fading and that the risks to financial stability looked to be contained (despite the combination of high yields and low growth).

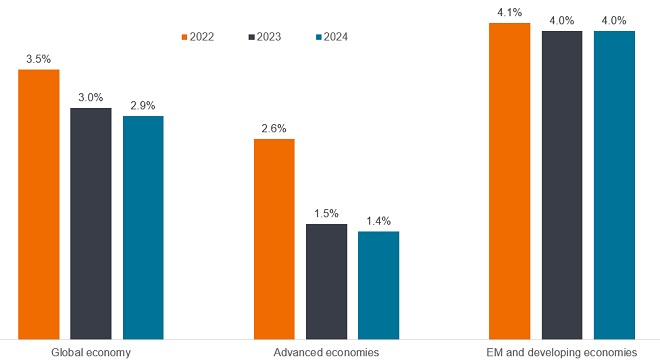

More sobering were the messages around moderating global growth. As shown in Figure 2, the IMF expects global growth to slow to 3% for 2023 and 2.9% in 2024, a 0.1 percentage point downgrade for 2024 from their July 2023 projections, and still well below the historical average.

Figure 2: IMF economic growth projections for 2023 and 2024

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook. Real GDP growth, percentage change. Data as of 10 October 2023.

Describing the global economy as “limping along”, the IMF opined that a “full recovery toward prepandemic trends appears increasingly out of reach, especially in emerging market and developing economies”. Nevertheless, one silver lining for Emerging Markets was that the recovery in the growth alpha (i.e., the difference between EM and DM growth) seen in 2023 is forecasted to be sustained in 2024 as well, making developing countries more attractive for global flows of capital.

The significance of this more muted growth outlook is that it makes it even more difficult to address global systemic challenges like climate change, military conflicts and migration, as well as domestic challenges like fiscal consolidation and aging. The IMF urged policymakers to use fiscal policy in support of monetary strategy and to focus – sooner rather than later – on rebuilding rapidly eroding fiscal buffers.5 Energy subsidies were highlighted again as a “bugbear” for their negative fiscal, social and environmental effects.6

Challenges of multilateral reform

Among the focal points of this year’s meetings were topics like the multilateral reform agenda (concerning the World Bank, but also other large MDBs – Multilateral Development Banks), the need to solve pressing global challenges (like poverty and climate) and discussions on how the World Bank, along with other MDBs, could increase their lending capacity.7 The International Development Association (IDA), the arm of the World Bank that provides the largest source of concessional and grant funding for the world’s poorest, has stretched itself to meet record demand at a time when low-income countries have seen many of the past decade’s development gains eroded by a series of exogenous shocks.

For EM debt investors such as Janus Henderson that rely on meticulous sovereign credit analysis in their investment process, subjects like the role of MDBs in catalysing private-sector capital inflows, the technical assistance and capacity-building activities they provide in EM, and their ability and willingness to lend during crises and use such lending as a vehicle for policy change all represent crucial points of interest, particularly at a time when access to global capital markets is either curtailed due to elevated borrowing costs, or barred altogether due to debt sustainability concerns.8

Behind closed doors – reforming Bretton Woods institutions

In general, there was a widespread perception that Bretton Woods institutions were “out-of-sync” with current market realities when pinning their hopes on large scale flows of private capital into EM to address the cost of climate transition. While many proposals on how to crowd-in private sector investors were brought forward, unfortunately few were deemed to be actionable by market participants.

We also noted a consensus on the need for MDBs to improve the narrative around private sector investing in EM, by emphasising the opportunities available and providing explicit and transparent mechanisms to mitigate some of the risks involved (like first-loss provisions, credit enhancements or the use of hybrid capital). While everyone agreed about the need to use the balance sheets of MDBs more aggressively, the fact that the Annual Meetings concluded without a capital increase for neither the IMF nor the World Bank was generally perceived as a disappointment.

Another important topic for EM investors revolved around various proposals to increase the lending capacity of the IMF via a so-called “quota reform”. Despite recognition that China and other EMs are currently underrepresented considering their economic and demographic weight, the US persisted with its preference for a proportional increase and offered developing countries more influence via changes in the Board structure. This was meant to deflect criticism that the US is failing in its support for poor countries, while at the same time putting China on the spot by giving it two unappealing choices: support a capital increase without getting its long overdue rise in its voting share, or resist the increase in the IMF’s lending capacity until a reallocation of voting power occurs, but in the meantime risk losing face with other developing nations who are in urgent need of help from the world’s official lender of last resort.

EM debt Portfolio Manager Sorin Pirău at the World Bank-IMF Annual Meetings in Marrakech.

Sovereign debt restructurings: an unfinished business

Improving the architecture of sovereign debt restructurings remains a work-in-progress. The meetings in Marrakech saw some small wins, building upon the progress we saw during the Spring Meetings in Washington DC back in April 2023, where an agreement was reached that MDBs would contribute to debt restructurings by providing net positive flows and concessional lending instead of having claims restructured.

Among the small wins was Zambia’s signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the country’s official creditors. For Sri Lanka, the agreement with China’s Exim Bank was meant to act like an “anchor” for other creditors and was immediately followed by a Staff Level Agreement for the first review of the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF) Arrangement.

The recently created Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) – a forum set up amid rising concerns over continued delays in securing debt treatment for countries in default – made limited progress, with discussions on the inclusion of domestic debt in restructuring plans for countries in default.9 The forum agreed that domestic debt restructurings sometimes could not be avoided, but technical issues again came to the fore with regards to Comparability of Treatment (CoT) considerations for creditors. No agreement was reached on a Net Present Value (NPV) formula or on which discount rate to use.

Discussions also focused on Value Recovery Instruments (VRIs) – instruments to facilitate debt restructurings by bridging the gap between debtors and creditors. To date, VRIs have had a mixed reception, largely on the grounds of valuation difficulties associated with their complexity, tradability, as well as lack of standardisation and lack of benchmark inclusion. Market participants expressed fears that EM investors would end up with a menu of various difficult-to-price instruments like Macro Linked Bonds (in Sri Lanka), GDP warrants (in Ukraine), oil warrants (in Suriname), debt-carrying-capacity-dependent VRIs (in Zambia) and additional structures that could apply to other countries in default such as Ghana or Venezuela. If you add to this mix debt-for-nature swaps, the landscape for debtors and creditors becomes even more labyrinthine. The clear message from investors was that given the preferences of asset owners for simplicity and income (i.e., coupon payments), finding a home for complex instruments in EM debt portfolios was proving to be extremely difficult.

Meetings with country delegations – summary observations

Pakistan. IMF “stabilisation package” is on track for now, with the first review coming in November. FX reserves have inched up to 1.5 months of imports. There are early signs of economic improvement on the back of normalisation of trade and investment flows. The financing outlook for 2024 depends on IFIs and bilateral creditors. Political environment is highly polarised with ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif contesting the upcoming elections in February, while Imran Khan, the country’s most popular politician, languishes in jail.

Turkey. Tries to position itself as the new darling of EM. Minister of Finance Mehmet Simsek and Central Bank Governor Hafize Gaye Erkan did a tour-de-force in Marrakech and were received with renewed optimism by investors. They emphasised that the recent policy shift is not temporary and that there is acceptance “at the highest levels” that the previous programme had failed to deliver.

Ukraine. Discussions were held under the shadow of the US Congress’ delay in approving further military and economic aid amid the very slow progress of Ukraine’s counteroffensive. The EU is trying to fill in the gap with a new €50bn facility for the next four years, but doubts abound about its commitment to fund the war effort (and subsequent reconstruction) in the absence of renewed US backing. Nevertheless, on the ground, the real economy has proven remarkably resilient with growth picking up and FX reserves reaching US$40bn thanks to a steady inflow of financial aid from the country’s Western partners.

Egypt. Has a challenging financing outlook to say the least. The decision to float the currency and get the IMF programme back on track has been delayed for political economy reasons. War in Gaza may hurt tourism and investment flows but will also underline Egypt’s role in the security architecture of the Middle East and thus may help unlock further bilateral and multilateral aid.

Tunisia. A better macro performance has allowed the government to delay subsidy reform and push the IMF programme into 2024. Supported by bilateral and multilateral funding, President Kais Saied will only engage with the IMF under his own terms and with an eye on the upcoming elections. The migration issue will keep EU countries involved and willing to help as long as Tunisia remains engaged.

North Macedonia & Montenegro. Fundamentally constructive. EU accession is suddenly back on the cards after the war in Ukraine underlined the strategic vulnerability of keeping the Western Balkans at the doorstep of the Union. Infrastructure modernisation (mainly roads, railways, and ports) supports their ambition to benefit from upcoming nearshoring opportunities.

Footnotes

1 Each year, the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group (WBG) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) meet to discuss the work of their respective institutions. The Annual Meetings, which generally take place in September/October, have customarily been held in Washington for two consecutive years and in another member country in the third year. The meetings bring together central bankers, ministers of finance and development, private sector executives, civil society, media and academics to discuss issues of global concern, including the world economic outlook, global financial stability, poverty eradication, inclusive economic growth and job creation, and climate change.

2 The first time the World Bank and IMF Annual Meetings were held in Africa was in Nairobi, Kenya in 1973.

3 The 6.8 magnitude earthquake in Morocco on Friday, 8 September 2023 was the strongest earthquake to have hit the country since the 1960s. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, more than 300,000 people in Marrakech and its outskirts were affected.

4 The JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD) tracks liquid US dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities and is a widely followed benchmark.

5 Fiscal buffers have eroded in many countries, with elevated debt levels, rising funding costs, slowing growth, and an increasing mismatch between the growing demands on the state and available fiscal resources leaving many countries more vulnerable to crises.

6 “Fiscal policy everywhere should focus on rebuilding fiscal buffers that have been severely eroded by the pandemic and the energy crisis, for instance, by removing energy subsidies.” – extract from Foreword to the 10 October IMF WEO report.

7 For more information about MDB reforms, see the Center for Global Development’s Multilateral Development Bank Reform Tracker, introduced on 9 October 2023 (https://www.cgdev.org/page/mdb-reform-tracker).

8 The latest available World Bank data on low-income countries included in their Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries lists 10 countries in overall debt distress (all but one, in Africa) and another 29 countries at high risk of overall debt distress.

9 The Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) started its work in February 2023. Prior to the October 2023 IMF-WB meetings, the GSDR met in April 2023, in the context of the IMF-WB Spring meetings.

Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR): A unique roundtable that provides, inter alia, a platform for debtor countries to request changes in the restructuring process. The objective of the GSDR is to build greater common understanding among key stakeholders involved in debt restructurings and work together on the current shortcomings in debt restructuring processes, both within and outside the Common Framework, and ways to address them. The roundtable is co-chaired by the IMF, World Bank and India (G20 Presidency) and comprises official bilateral creditors (both traditional creditors members of the Paris Club and new creditors), private creditors and borrowing countries. According to the IMF, the focus of the GSDR is on process and standards, not to discuss country cases. The GSDR will not replace existing restructuring mechanisms such as the Common Framework.

Comparability of Treatment (CoT): A term referring to the principle that all creditors should be treated equally. CoT is the Paris Club official creditor nations’ principle intended to ensure that the claims of Paris Club members are not subordinate to private institutions or other bilateral members who are not in the group (e.g., China). The G20s Common Framework for Debt Treatments architecture – an internationally agreed process for coordinating the restructuring of the debt of low-income countries, launched in November 2020 – also relies on the CoT principle. However, as at November 2023, the challenge of identifying a methodology for assessing CoT remains.

Value Recovery Instruments (VRIs): VRIs are instruments intended to facilitate debt restructurings by allowing creditors to share the prospective “upside” of economic recovery with the debtor country and to compensate creditors for granting debt reduction in the restructuring process. Value recovery mechanisms are a subset of sovereign state-contingent debt instruments (SCDIs). VRIs are typically structured as derivative securities, with payouts linked to a state variable such as GDP, commodity prices or exports. An example of a VRI is a GDP-linked warrant (GLW), which allows investors to receive extra payouts when GDP growth exceeds certain thresholds. According to the IMF, the use of VRIs in past debt restructuring cases has been sporadic.

Debt-for-nature swaps: Financial transactions in which a portion of a developing nation’s foreign debt is forgiven in exchange for commitments to environmental conservation measures such as decarbonisation, forest protection or investment in climate-resilient infrastructure. Debt-for-nature swaps are intended to help low- and middle-income countries address the triple challenge of high debts (fiscal risks), climate change vulnerability and biodiversity loss.

Multilateral Development Bank (MDB): A supranational financial institution established by multiple member countries to facilitate low-cost financing to developing countries with a view to fostering economic and social progress. MDBs also provide advisory services to developing countries. MDBs are sometimes also referred to as International Financial Institutions (IFIs). MDBs also play a major role in international capital markets, where they raise the large volume of funds required to finance their loans. Major MDBs include the European Investment Bank, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank Group), the Asian Development Bank, the International Development Association (World Bank Group), the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the African Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, and the New Development Bank. According to the US Department of the Treasury, during the global financial crisis – a time when few institutions were lending – “MDBs provided $222 billion in financing, which was critical to global stabilization efforts”. (https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/international/multilateral-development-banks)

Bretton Woods: The Bretton Woods Agreement and System created a collective currency pegging regime in the mid-1940s as well as two institutions: the IMF and the World Bank. The overarching aims of Bretton Woods included rebuilding war-ravaged nations, promoting international trade and economic growth across borders, and stabilizing the post-war international financial system. Although the Bretton Woods currency pegging system collapsed in the early 1970s, the IMF and World Bank have continued to have significant influence on international capital finance and trade.

The World Bank: The World Bank plays a key role in the global effort to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. Working in more than 100 countries, the World Bank provides financing, advice and other solutions that enable countries to address the most urgent challenges of development.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF): The IMF is a global organization that works to achieve sustainable growth and prosperity for all its 190 member countries. It does so by supporting economic policies that promote financial stability and monetary cooperation, which are essential to increase productivity, job creation and economic well-being. The IMF is governed by and accountable to its member countries.

Foreign Direct Investment: Foreign direct investment (FDI) is the category of international investment that reflects the objective of obtaining a lasting interest by an investor in one economy in an enterprise resident in another economy.

GDP: The value of all finished goods and services produced by a country, within a specific time period (usually quarterly or annually). It is usually expressed as a percentage comparison to a previous time period and is a broad measure of a country’s overall economic activity.

Debt-to-GDP ratio: The debt-to-GDP ratio is the metric comparing a country’s public debt to its gross domestic product (GDP).

Fiscal policy: Connected with government taxes, debts and spending. Government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. It is separate from monetary policy, which is typically set by a central bank. Fiscal austerity refers to raising taxes and/or cutting spending in an attempt to reduce government debt. Fiscal expansion (or ‘stimulus’) refers to an increase in government spending and/or a reduction in taxes.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money. See also fiscal policy.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Emerging market investments have historically been subject to significant gains and/or losses. As such, returns may be subject to volatility.