Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Paul O’Connor, Head of the UK-based Janus Henderson Multi-Asset Team, examines the economic runes as 2019 dawns in the latest issue of Multi-Asset Perspectives, our quarterly outlook for multi-asset investors.

The ferocity of the market sell-off in the final months of 2018 has cast a huge shadow over the investment outlook for the New Year. The big question now facing investors is whether the correction has created an attractive entry point for putting money to work or whether we are at the start of a sustained downtrend in risk assets. We lean towards the former view and think that investors will ultimately be rewarded for riding out the current market turbulence. We take comfort from the fact that global economic fundamentals remain in good shape, interest rates are likely to remain low and risk-asset valuations have improved over the past year. Of course, we must acknowledge the challenge to financial markets, from the maturity of the economic cycle to the ending of central bank asset purchases, but feel that these risks are now widely understood and well priced in. We expect that investment returns in most asset classes in 2019 will be better than those experienced in the previous 12 months but still anticipate an eventful and challenging year in the markets – an environment best suited to those flexible enough to shift nimbly between asset classes.

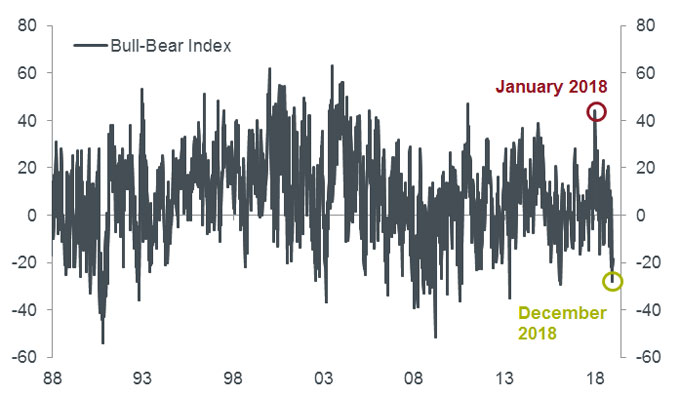

2018 was undoubtedly a transition year for financial markets, away from the unusually benign investing conditions of the preceding years, to a more difficult and complicated environment. The resetting of expectations was a key theme of 2018. The year began with investors unusually optimistic about equities and other risk assets, having enjoyed two years of strong returns and low volatility. One well-known measure of US retail investor sentiment (the Bull-Bear spread, see chart below) showed that bullishness about the stock market in January was in the top 97% of all-time readings. The same sentiment was evident across a broad range of other assets as well. Corporate bond spreads, for example, began the year at, or close to, post-crisis lows.

While investors began 2018 confident to the point of complacency, they spent most of the year reappraising their expectations and repricing risk as more challenging news emerged on the growth, policy and political fronts. This process gathered momentum into the final months of the year, with some hair-raising moves in Q4, including a near 20% drawdown in the S&P 500 Index and more than a 40% decline in crude oil prices. By December, after a gruelling year in all risk assets, evidence of investor capitulation was widespread. That month saw the greatest ever week of redemptions from global equities and bonds, confirming that the consensus mood had swung from January’s unusually bullish readings to deep gloom by year end. By December, the Bull-Bear spread had fallen below the third percentile of all-time readings.

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018. Spread is difference between ‘bullish’ and ‘bearish’ readings of the weekly survey of the American Association of Individual Investors.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018. Spread is difference between ‘bullish’ and ‘bearish’ readings of the weekly survey of the American Association of Individual Investors.[/caption]

Whereas widespread investor complacency at the start of 2018 made us wary of the market outlook back then, we take some contrarian encouragement from the gloomy consensus prevailing at the start of this year. It suggests to us that financial markets have adjusted to more fully price in many of the key risks that investors have been grappling with in recent months. Asset valuations convey a similar message. While, we can’t say that all risk assets are now outstandingly ‘cheap’, valuations are more attractive than they were at the start of 2018 and have reset to levels from which reasonable medium-term investment returns can be anticipated.

[caption id=”attachment_77330″ align=”alignnone” width=”680″] Source: Bloomberg as at 31 December 2018. ‘YE’ = ‘Year End’ ‘m’ = ‘month’.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg as at 31 December 2018. ‘YE’ = ‘Year End’ ‘m’ = ‘month’.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018.[/caption]

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

While there are, of course, a number of sizable and significant uncertainties overshadowing the investment outlook for 2019, our base case scenario for global macroeconomic fundamentals remains fairly market friendly. As the US economic expansion approaches its longest ever run, we see no reason yet to abandon our expectation of it continuing, sustaining decent corporate earnings growth and low corporate default rates. A belief that the subdued inflation outlook in the major economies will keep interest rates low for the foreseeable future is a key assumption underpinning this long-cycle view. The interest rate outlook, in our opinion, is not notably different from what is currently indicated by financial markets: policy interest rates in two years’ time to be close to zero in the Eurozone and Japan, 1% to 1.25% in the UK and somewhere between 2.5% and 2.75% in the US.

Of course, the timing of the next US recession has become a major debate among investors in recent months, understandably, given the unusual duration of the current US recovery and the tight link between recessions and bear markets. While we agree that a high degree of vigilance is warranted here, we see little convincing evidence to suggest that a US recession is imminent and feel that a US soft landing is still a realistic central scenario for 2019. In terms of the economic lead indicators of recession, we are particularly focused on labour market data, which have given reliable warnings of major economic downturns in the past. The rule of thumb here is that recessions usually occur about a year after unemployment claims or the unemployment rate turns up. Both are still trending lower.

We expect that growth in the world economy will slow modestly in 2019 with most of the adjustment being due to a deceleration in the US, as the effects of the 2017/18 fiscal stimulus recede and the effects are felt of recent increases in interest rates, bond yields and the US dollar. Outside of the US, we expect growth rates for most of the major economies to be fairly similar to those in 2018. An important assumption here is that Chinese macroeconomic momentum stabilises, after decelerating for most of the past year. While Chinese policymakers continue to face the difficult task of juggling some conflicting policy objectives, we do believe that the emerging round of stimulus measures will stabilise growth in 2019, as has been the case in four mini-cycles since 2008.

Away from the ebb and flow of the economic cycle, 2018 was a year in which investors were forced to confront a number of unprecedented and difficult-to-calibrate policy and political risks. The most significant one was the ending of quantitative easing (QE), after a decade in which central banks injected about $11,000 billion into financial markets through their asset purchase schemes. Given that this was an unparalleled experiment, we don’t really know how its ending will affect financial markets. Our long-held view is still that it marks a regime change in financial markets, ushering in a more challenging environment of lower returns and higher volatility than enjoyed during the QE era. To some extent, we would see the market turbulence witnessed in 2018 as reflecting investors’ adjustment to this new world.

The other big policy question overshadowing the market outlook is whether international trade tensions will escalate again, threatening global economic confidence and growth. While this topic dominated market sentiment at different times in 2018, we feel that concern on this front has already peaked, given that a lot of bad news is now factored in and progress has been made to de-escalate trade tensions in a number of important areas recently, most notably on the US-China front.

Beyond policy matters, we expect that political flare-ups will demand investor attention once again in in 2019. The US government shutdown, developments in Italy and the Brexit negotiations look most likely to generate market-moving headlines in the early months of the year.

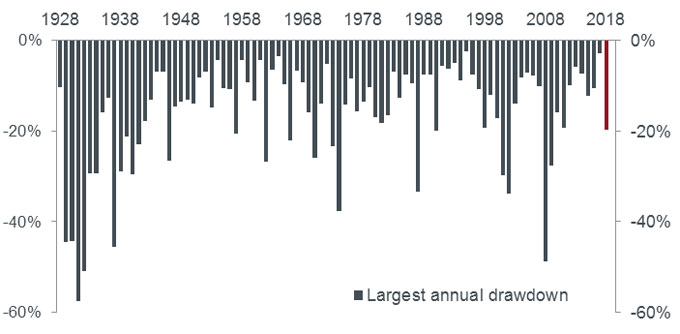

With both policy and political uncertainty looking set to be unusually high in 2019, faith in our constructive long-cycle scenario is likely to be frequently tested. If our big picture view is broadly correct, then investors will need to learn to trade against the oscillations in investor sentiment that we expect to be a defining feature of the market environment in 2019. The days of QE-becalmed financial markets are over – volatility is back and we all have to learn to deal with that. History tells us that double-digit equity market pullbacks have been experienced in the US in roughly two out of every three years since 1928 and pullbacks of 15% or more have been seen about one year in three.

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 December 2018[/caption]

In summary, we expect most of the major asset classes to deliver better performance in 2019 than in 2018 but anticipate a bumpy ride with occasional nerve-testing setbacks. While buy-and-hold investing was the right approach when markets were trending strongly higher, the more turbulent market regime that we foresee will demand a greater emphasis on volatility management and dynamic asset allocation. Actively managed multi-asset funds should have plenty of appeal in this sort of environment, given the breadth of their opportunity set, their flexibility and their foundation of diversification.