Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

President Lula faces a Brazil that is very different to when he first came to office in 2003. Thomas Haugaard from the Emerging Markets Debt Hard Currency team explores the outlook for Brazil and the three constraints influencing Lula’s pursuit of his populist agenda.

| The JH Explorer series follows our investment teams across the globe and shares their on-the-ground research at a country and company level. |

Walking to our hotel in Rio, the celebrations for Carnival had started early.

We have just returned from a five-day trip to Latin America, spending three days in Brazil (Rio, Brasilia and São Paulo) followed by two days in Argentina (Buenos Aires). Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires are known for their bustle and energy with a mix of cultures from across the world seen in everything from dance to food. Arriving a week before the famous Rio Carnival was scheduled to begin, the streets were already teeming with people as preparations mounted for the big event.

We met with a broad set of experts including local investors, independent political and economic consultants as well as political actors. Sentiment across the board was negative overall. There was a clear lack of conviction among locals, who generally could not understand why foreign investors appear much less concerned and even somewhat constructive on the outlook for Brazil.

Admiring the view from our hotel, we recalled our last visit in 2016, when Brazil was managing its way out of a deep recession and political crisis following the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, who was Lula’s anointed heir back in 2010.

Before the October 2022 election, there was a strong sense that Lula da Silva, who was gunning for the role of president for a third time, would adopt a market-friendly approach, leaning to the centre and committing to responsible fiscal policies and more broadly to stability-oriented macro policies that characterised the previous Temer and Bolsonaro administrations. The consensus from our meetings is that Lula has so far disappointed on all possible accounts, including looser fiscal policy, acting as an ineffectual pseudo Minister of Finance (with Haddad the actual MoF having limited success so far in constraining Lula) as well as pressuring the central bank to cut interest rates.

This Lula appears not to be the same president he was in the past. He now has a determination to support economic growth quickly, almost at any cost to secure popularity.

Without significant checks and balances this could mean:

As the former President Dilma Rousseff put it: “Public spending is life!”

A high degree of uncertainty surrounds checks and balances given Lula’s majority in both chambers of Congress and the alignment of the Supreme Court with his Workers Party (PT). With former president Bolsonaro likely returning to Brazil soon, we could see a more concerted resistance to the above policy agenda from Congress; the coalition in Congress are, in our view, fragile and sensitive to populist policy initiatives.

While the change in the fiscal framework is still uncertain, all signals point to a weaker and more flexible policy where accountability is less clear. This scenario is likely unless Congress or financial markets effectively constrain Lula and his government to moderate. While Congress has shown some ability and willingness to do this, the constitutional amendment allowing for more social spending in 2023 still resulted in more funds than expected. We see less sensitivity from the Lula administration to financial market reactions to policies, but when Lula mooted a higher 4.5% inflation target right after the election, the market reacted badly, which led Lula to eventually tone down his rhetoric.

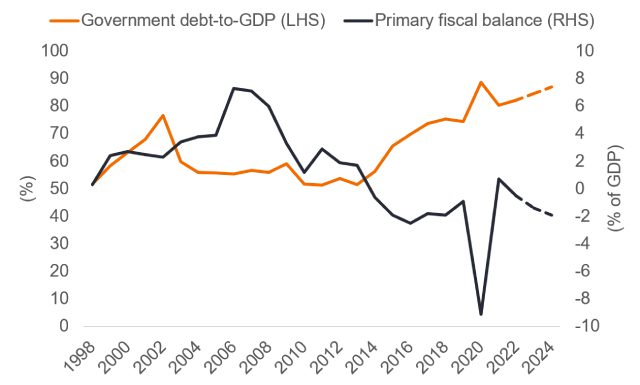

From our conversations, we expect double-digit increases in Brazil’s debt-to-GDP ratio under Lula. A primary surplus (currently a deficit) of 2.5% is needed to stabilise debt-to-GDP, an outcome we find highly unlikely under the Lula administration. While the most recently announced fiscal consolidation plan indicated a primary deficit between 0.5 and 1% of GDP, even the MoF himself signalled scepticism about his own plan to reduce the deficit. The announcement was likely made to convince the central bank to consider cutting rates sooner. The combination of these factors leads us to think that in the coming years, debt conditions in Brazil will likely deteriorate and policies will be less market friendly as the state takes a more central role in the economy like it did in the past. It does not appear that Lula’s PT Party has learned much since it was last in power. The biggest risk to policy quality is slow economic growth (driving a deterioration), while the opposite would likely lead to some moderation in Lula’s populist rhetoric.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Moody’s, 27 February 2023. 2023 and 2024 figures are estimates. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised. The debt-to-GDP ratio is the metric comparing a country’s public debt to its gross domestic product (GDP). The primary balance is the fiscal balance excluding net interest payments on public debt. In other words, the difference between the amount of revenue a government collects and the amount it spends on providing public goods and services.

While economic growth is slowing in Brazil, strong external demand from booming commodity exports (a very strong harvest in particular) has been a tailwind and unemployment remains relatively low. Going forward, the main economic headwind is the exceptionally high real interest rate and what appears to be a credit overhang in the household sector.

Even as the economy is decelerating, inflation remains stubbornly high and recent inflation expectations have unanchored due to signals of loose fiscal spending, amplified by the absence of a clear fiscal anchor. Lack of policy coordination and higher inflation expectations present a significant challenge for the central bank. Without political interference, it could soon be able to loosen monetary policy, but now that is difficult as inflation expectations could unanchor even more if the bank is perceived to bow to political pressures. Hence, it is waiting for some visibility on the fiscal front.

Post the unveiling of the fiscal framework expected in April, it is highly likely that the government will push for an increase in the inflation target to at least 4% (most likely by June). This is key to watch as the government believes that this would give room for the central bank to cut rates, but the central bank will watch inflation expectations carefully and any sign of further unanchoring could actually lessen the chance of cuts. Nevertheless, there is a decent chance that the economy could decelerate significantly by then, allowing the central bank to cut rates without looking like it is succumbing to political pressures. Financial markets fear a replay of what happened in the Dilma era, when political pressure led to central bank governor Tombini clearly targeting the upper limit of the inflation band and not the target, leaving inflation expectations at the upper limit.

The Brazil that President Lula faces today is very different than the Brazil he faced during his first terms in office. It is clear that he has a strong preference for more state involvement to promote economic growth to secure his and PT’s popularity. However, we believe three constraints will influence Lula’s ability pursue his agenda:

There are glimmers of hope for Brazil, however deteriorating debt dynamics amid slowing economic growth, more state-involvement and less market-friendly policies have led us to remain cautious on the outlook for Brazil.

Fiscal/Fiscal policy: Connected with government taxes, debts and spending. Government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. It is separate from monetary policy, which is typically set by a central bank. Fiscal austerity refers to raising taxes and/or cutting spending in an attempt to reduce government debt. Fiscal expansion (or ‘stimulus’) refers to an increase in government spending and/or a reduction in taxes.

Fiscal framework: National fiscal frameworks are rules, regulations and procedures that influence how budgetary policy is planned, approved, carried out, monitored and evaluated.

Checks and balances: Checks and balances are the mechanisms which distribute power throughout a political system – preventing any one institution or individual from exercising total control.

Fiscal anchor: This can be defined as adopting guidelines or limits on a fiscal metric or series of metrics to ensure the sustainability of the government’s fiscal position.

Primary surplus: A primary budget surplus occurs when tax revenues are greater than government spending (excluding debt interest payments)

Gross domestic product (GDP): The value of all finished goods and services produced by a country, within a specific time period (usually quarterly or annually). It is usually expressed as a percentage comparison to a previous time period, and is a broad measure of a country’s overall economic activity.

Inflation: The rate at which the prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. The CPI and RPI are two common measures. The opposite of deflation.

Credit overhang: a debt burden so large that an entity cannot take on additional debt to finance future projects.

Fiscal consolidation: Government policy intended to reduce deficits and the accumulation of debt.