Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Jim Cielinski believes 2023 should bring relief on rates as central bankers recognise their servings of policy tightening are dampening inflation but the corporate outlook is set to be more challenged.

Anyone who has made a béchamel or white sauce will recognise the dilemma facing central bankers. At first the combination of milk, butter, and flour remains a runny liquid. You stir over the heat, but it refuses to thicken. So you add more flour. Nothing happens. You add more flour. Still no response. The temptation is to keep adding flour, but there is a risk. The compounding effect of all that flour, together with the heat, creates a reaction, and all at once the sauce turns far too thick and lumpy.

Central bankers’ policy tightening is the flour and the transmission mechanism (how that tightening feeds through to the economy) is the heat. The outlook for the global economy in the year ahead is lumpy as tighter financial conditions provoke material growth slowdowns and recessions. Yet, for many parts of the fixed income market, 2023 could prove to be a far more appetising year.

The past year was unpleasant for fixed income as inflation soared and the distortions to asset prices created by quantitative easing unwound. As central banks stepped back from repressing yields, price discovery returned. Bond yields rose sharply, producing some of the worst total returns in the history of fixed income.1

Yet, the pain in fixed income markets has arguably been front loaded, much like the US Federal Reserve (Fed) front loaded its interest rate hikes with consecutive 75 basis-point increments. We should not expect the same in 2023. The starting point of higher yields and wider credit spreads should offer a healthier outcome for bond investors.

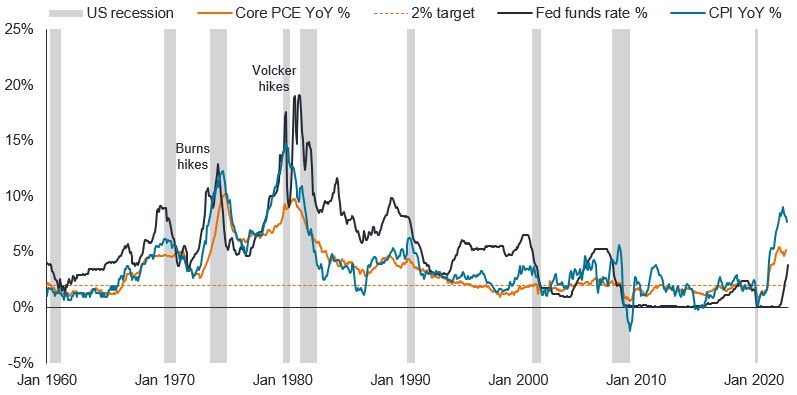

How central bankers calibrate monetary policy to control inflation without causing too much economic damage will dominate markets and we can expect market volatility to persist around their announcements. Previous inflationary episodes are instructive. As Figure 1 shows, the fast pace of US rate hikes in 2022 has only previously been seen under Fed Chairmen Arthur Burns in the mid-1970s and Paul Volcker in 1979 and 1980 – both periods of rampant inflation.

Two things are worth noting:

For these reasons, and because we expect the US economy to outperform most other developed market economies, we think the Fed will remain tough on tackling inflation. In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) may pause their tightening earlier, but even there a resolute focus on inflation will likely keep the hawkish rhetoric flowing for longer than the economies can tolerate.

Several factors kept inflation stuck at a high level in 2022, including supply chain problems, the Russia-Ukraine conflict and, in the US, the pass-through of shelter costs in the Consumer Price Index. These should fade, with goods prices leading the decline and base effects making it hard to sustain high year-on-year inflation numbers. We expect inflation in the US to soften but remain above the Fed’s target 2% rate. Europe’s reliance on imported oil and gas aggravates the inflation outlook there, but progress in diversifying energy imports and reducing energy use mean further shocks would be linked to weather or geopolitics.

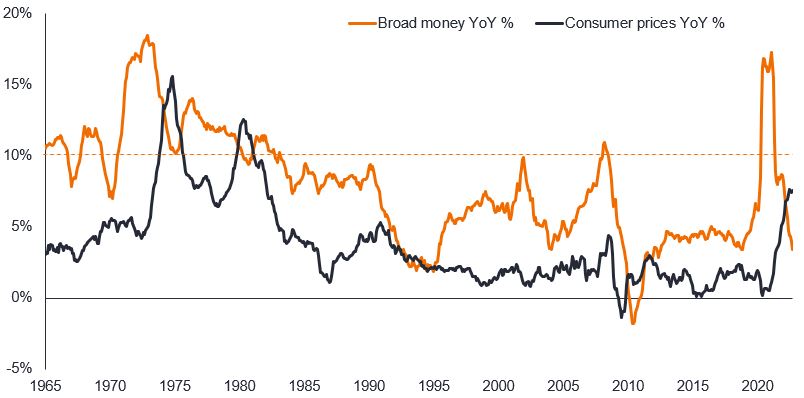

We take comfort in the fact that broad money growth (which has typically heralded the direction of inflation) has receded in developed markets since peaking in 2021 (Figure 2). This suggests inflation will retreat in 2023 and not persist as it did in the inflationary 1970s, when broad money growth never fell below 10%.

The key question is, can the Fed engineer a soft landing and avoid overtightening? The answer may lie in the labour market response. Previous tightening cycles relied on rising unemployment to contain wage growth and prevent high inflation from becoming embedded. Economic conditions today would seem to favour workers, making the Fed’s job much harder (Figure 3).

| Tightening cycle | 1965/6 | 1983/4 | 1994/5 | Oct 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate (%) | 3.9 | 8.7 | 6.0 | 3.7 |

| Vacancy-to-unemployment ratio | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| Wage inflation (YoY %) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 5.5 |

| Interest rate > inflation rate? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Source: Bloomberg, Refinitiv Datastream, Janus Henderson Investors, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Unemployment rate: US unemployment rate average during tightening cycles and as at 31 October 2022. Vacancy-to-unemployment ratio: Conference Board Help Wanted to number unemployed average ratio during tightening cycles and BLS job openings rate divided by unemployment rate as at September 2022. Wage inflation: BLS average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees, total private, YoY change, seasonally adjusted, average during tightening cycles and as at 31 October 2022. Interest rate is fed funds rate and inflation is US CPI YoY % during tightening cycles and as at 31 October 2022.

We think that the cumulative lagged effect of earlier tightening, and even certain global forces, will begin to impress on Fed thinking. Leading economic indicators globally are predicting one thing: recession. We must be careful when reading some forward-looking survey data as they can often describe a change in direction but not magnitude. Nevertheless, many new orders surveys are declining, and most consumer sentiment indices are bleak.

Tighter financial conditions are already being felt. Rate-sensitive areas of the economy are responding fast to higher financing costs. Take housing: in the US, the 30-year mortgage rate has climbed from 3.1% to 7.1% in a year; in the UK, the 5-year rate has risen from 2.7% to 5.6%.2 Such big moves will eventually crack the housing market, and we have already seen central banks in Australia and Canada embrace smaller rate hikes as the lagged impact of monetary tightening bites. In our view, this is the start of a climbdown that other developed market central banks will follow in 2023.

Interest rate risk was the principal risk to fixed income in 2022 as rising rates sent asset prices tumbling. That is set to change. In fact, interest rate risk could turn beneficial if, as we expect, rates peak in 2023 and an opening to a declining rate trajectory emerges. As Figure 4 shows, nominal yields at 4% on the 10-year US government bond are now high enough to appeal to income investors and offer some capital appreciation during risk-off environments. What is more, real yields (those adjusted for inflation) are positive.

10-year US government bond real and nominal yields both firmly positive.

In contrast, credit risk is rising as corporate fundamentals weaken, which raises questions around companies’ ability to meet their debt repayments to investors. Company earnings have been surprisingly resilient, but a slowdown emerged in Q3 2022 reported figures. With inventory levels high and consumers retrenching, we think coming quarters will deteriorate further. Companies can also anticipate less fiscal support as governments seek to reduce their deficits post COVID. We expect credit rating agencies to downgrade more companies, with ratings downgrades outpacing upgrades in 2023.

Defaults are also set to rise. Typically, this happens when companies struggle to refinance. Many companies were able to term out their debt, extending the years to maturity and raising money at low rates in recent years. The COVID crisis also flushed out many of the weaker issuers, and the credit quality of borrowers is high relative to history. While this offers the prospect of a more subdued default path, we still expect the global high yield default rate to double to around 4-5% by late 2023.3 But while default rates in the US and Europe should rise, we will watch for the rate in Asia to decline as the deleveraging policies in China, which led to heavy property sector defaults, may be mostly behind us.

The prospect of more downgrades and defaults means assessment of credit fundamentals will be paramount, creating alpha opportunities from avoiding the losers and picking the winners.

Liquidity concerns should not be overlooked in 2023. The problems in the UK around the mini-budget and the fallout in its gilt and pensions market are an example of how financial instability often rises around periods of tighter policy. Both the Fed and the BoE have embarked on quantitative tightening (QT), allowing bonds to mature or actively selling them. This removes a somewhat price-insensitive buyer, potentially increasing stress in the markets.

While the ECB has not yet formally announced QT, it has altered the conditions on its targeted longer-term refinancing operation (TLTRO). This move is encouraging commercial banks to repay TLTRO loans early, which could lead to a €1.2 trillion reduction of the ECB balance sheet by June 2023. Nor have peripheral eurozone sovereign bond concerns disappeared. The ECB’s new Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) allows the bank to buy sovereign bonds of countries suffering weakening financial conditions caused by its monetary policy, but this is the first time we have seen such a rapid repricing of Bund yields. So we are in uncharted territory in terms of whether eurozone sovereign bond yields can remain anchored – another reason to think the ECB will be more cautious around tightening than the Fed.

Japan could also be interesting. Haruhiko Kuroda’s term as governor of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) ends in April 2023, and he has been a staunch advocate of the BoJ’s negative interest rate policy and yield curve control. Soft global growth in 2023 makes it unlikely that the BoJ will move away from its ultra-loose policy stance, but any sign of change could have implications for capital flows.

Looking across fixed income, we think developed market sovereign debt appears attractive, with yields having priced in most of the tightening and paving the way for a rally around the prospect of an end to the tightening cycle. The US and Europe look to offer better opportunities than the UK gilt market, which may face indigestion from high supply and the BoE engaging in QT. Signs of a peak in US rates may also be supportive for emerging market (EM) debt, as might a rebound in China’s economy for EM exporters. It is worth remembering that some EM countries such as Brazil tightened early and have already had some success in moderating inflation. While nearly all central banks were on a rapid tightening footing in 2022, we expect more dispersion in monetary policy and economic outcomes in 2023.

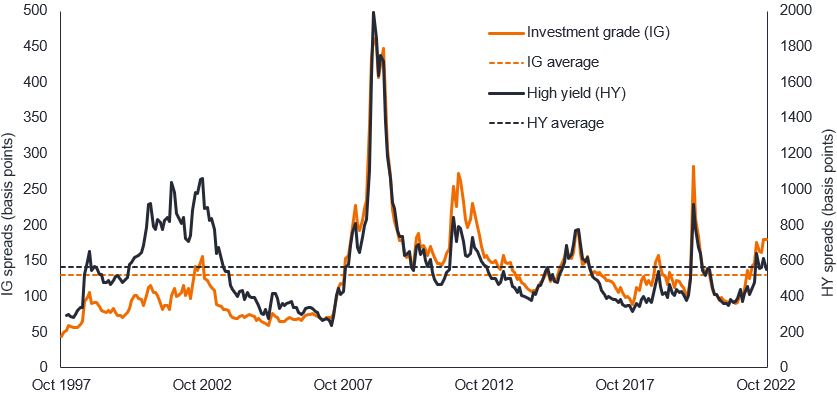

We lean towards favouring higher quality assets over more leveraged assets as a weak growth environment is likely to favour more stable issuers. We think value is emerging in investment grade (IG) corporate bonds. As Figure 5 shows, these are doing a better job reflecting credit risk than high yield debt, with spreads well above average levels.

Investment grade spreads are above average levels.

That does not mean spreads are immune to further widening. Early 2023 could be trying as earnings uncertainty peaks, but we think this will pass. An underappreciated phenomenon is the disconnect between real and nominal economic growth numbers in this cycle. Economic growth figures are normally quoted in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, but corporate revenues are in nominal terms, which helps explain why earnings and cash flows have remained high. We think this may help bridge the gap between weak sentiment and resilient cash flows, and with investment grade debt being more sensitive to rates movements than high yield, put it in a stronger place to outperform.

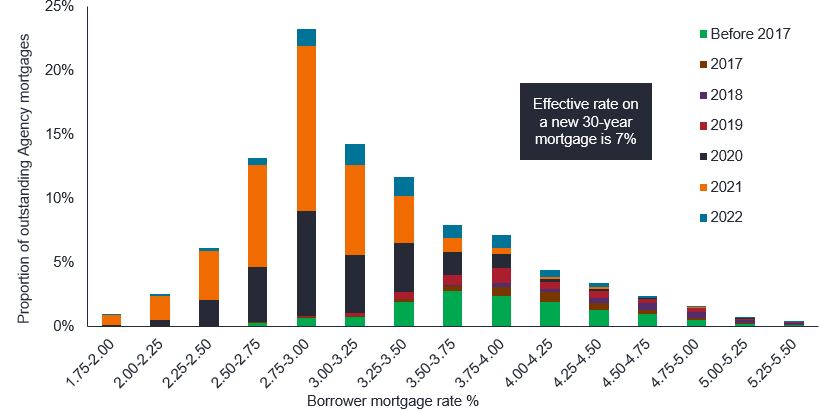

Elsewhere, rates volatility has caused spreads on mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to widen to attractive levels at a time when regulation around risk-weighted assets has prompted commercial banks to step back from buying MBS while they build their capital ratios. This process may be nearing an end, however, and while the Fed’s QT means it is allowing existing holdings of MBS on its balance sheet to passively decline as the principal is paid off, we think active selling by the Fed is unlikely. MBS spreads are high at a time when the risk of pre-payment is small since few households will want to refinance their mortgage now that mortgage rates are around 7% (see Figure 6).

The slowing economy is also likely to reassert the importance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors. Controversies typically get exposed during challenging times when companies are under more scrutiny, so social and governance factors, with their focus on reputational and financial risk, have added resonance. In terms of environmental factors, the spotlight on energy efficiency means 2023 should be another year of strong green bond issuance within utilities and real estate and we would expect transition financing to grow as borrowers in high carbon-emitting sectors seek to link new issues with demonstrable progress on energy transitioning.

The higher yields on fixed income have restored the income qualities and likely the diversification benefits of the asset class. With pension solvency ratios much improved, we also think there may be less incentive to own riskier assets, creating demand for fixed income.

A slowdown is in the cards, but that is well-telegraphed. The key is whether inflation can slow quickly enough to preclude policymakers from over-tightening and creating severe stresses in the financial system. With the arrival of a well-anticipated global slowdown, however, investors are greeted by higher yields and higher potential returns. Thus, we believe the coming year should prove to be a more appetising one for fixed income investors.

1 Source: Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index declined 13.2% in 2022 (up to 16 November 2022), the worst annual total return since the index formed in 1976, Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index (hedged to USD) fell 10.6% in 2022, the worst annual total return since the index formed in 1990. Returns in US dollars.

2 Source: Bloomberg, Freddie Mac US 30-year Mortgage rate, Bank of England 5-year mortgage rate, percentage rates at 31 October 2021 and 31 October 2022.

3 Source: This compares with the Moody’s trailing 12-month global speculative-grade corporate default rate of 2.3% at 30 September 2022.

10-year Treasury yield is the interest rate on US Treasury bonds that will mature 10 years from the date of purchase.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based measure of the global investment grade fixed-rate debt markets.

Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based measure of the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market.

Breakeven rate: The difference in yield between inflation-protected and nominal debt of the same maturity.The result is the implied inflation rate for the term of the stated maturity.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

Credit ratings: A score given by a credit rating agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s and Fitch on the creditworthiness of a borrower. For example, S&P ranks high yields bonds from BB through B down to CCC in terms of declining quality and greater risk, i.e. CCC rated borrowers carry a greater risk of default.

Credit risk: The risk that a borrower will default on its contractual obligations, by failing to meet the required debt payments.

Credit spread is the difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due. The default rate is typically expressed as a percentage rate reflecting the face value of bonds in an index defaulting over a 12-month period compared with the total face value of bonds in the index at the start of the period.

Federal Reserve or Fed is the central banking system of the United States.

Financial conditions: The ease with which finance can be accessed by companies and households. When financial conditions are tighter it is harder or more costly for people and businesses to access finance.

Fiscal policy: Government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. Fiscal support/expansion/stimulus refers to an increase in government spending and/or a reduction in taxes.

Green bond: Bonds that provide a means of raising funds by companies and governments via the debt capital markets for projects that deliver environmental / sustainable benefits and solutions.

Hawkish is indication that policy makers are looking to tighten financial conditions, for example, by supporting higher interest rates to curb inflation.

High yield bond: A bond that has a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond. Sometimes known as a sub- or below investment grade bond. These bonds carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher coupon (regular interest payment) to help compensate for the additional risk.

Inflation: The annual rate of change in prices, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

Interest rate risk: The risk to bond prices caused by changes in interest rates. Bond prices move in the opposite direction to their yields, so a rise in rates and yields causes bond prices to fall and vice versa.

Investment grade: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments. The higher quality of these bonds is reflected in their higher credit ratings.

Leverage: This is a measure of the level of debt in a company. Gross leverage is debt as a ratio of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money. Monetary easing/stimulus refers to a central bank lowering borrowing costs and increasing the supply of money. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Option-adjusted spread (OAS) measures the spread between a fixed-income security rate and the risk-free rate of return, which is adjusted to take into account an embedded option.

Quantitative tightening (QT): contractionary monetary policy in which central banks decrease the supply of money in the economy by shrinking their balance sheets – this can be achieved by passively allowing bonds to mature and deleting them from its cash balances or actively selling bonds to drain money from the wider system.

Real yield: A real yield is calculated by subtracting the expected inflation rate from a bond’s nominal yield.

Recession: A significant decline in economic activity lasting longer than a few months. A soft landing is a slowdown in economic growth that avoids a recession.

TLTRO: Targeted longer term refinancing operations were a form of cheap borrowing for commercial banks in the eurozone, designed to encourage lending.

US Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the US Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and US Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. The higher the volatility means the higher the risk of the investment.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Equity securities are subject to risks including market risk. Returns will fluctuate in response to issuer, political and economic developments.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Securitized products, such as mortgage- and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed-income securities.