Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Natasha Page, Director of Fixed Income ESG, counters criticism of ESG amid higher energy prices, explaining how it is part of the solution.

The insurance industry is a US$5.2 trillion global industry, representing around 9% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.1 It exists because people are precautionary. None of us knows precisely what the future holds so we seek to mitigate those risks.

If your car gets stolen, you do not cut the collision damage insurance and focus solely on insuring against theft – you would continue to pay for coverage for both as the probability of collision in the future is unaffected. In probability terms they might be classed as mutually exclusive (although given that stolen cars are involved in an inordinate amount of car accidents, perhaps not).

So what has that got to do with environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing? A year ago ESG dominated the agenda, culminating in global leaders making a strong commitment to address climate change at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26).

Fast forward to 2022, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict has created a more challenging climate. Supply constraints and sanctions have combined to make energy more expensive and disparaging accusations have been aimed at ESG as energy prices have rocketed. “Underinvestment in fossil fuels is to blame.” Refrains such as these have recently become commonplace and ignore the counterfactual that if more had been spent on renewables and energy storage, there might be less reliance on fossil fuels today. Moreover, they absolve the real reason for high gas prices – the disruption to gas supplies coming from Russia.

The consequences of such sentiment are reflected in the actions of some US states that are actively legislating against ESG, and by some asset managers that have launched funds clearly distancing themselves from ESG considerations.

But higher energy prices should not mean abandoning ESG as some would advocate, least of all running at full speed into fossil fuel investing. Within Janus Henderson Fixed Income, we believe that pure divestment from higher-polluting sectors is not the sole answer to resolving climate problems. Indeed, our focus is on supporting, through investment and engagement, those companies (including in the fossil fuel industry) that are making credible efforts to responsibly transition towards cleaner, renewable energy generation. One thing is clear, however: this will not happen overnight.

It is important to remember that commodity prices can be highly volatile and the energy sector is one that demands careful credit analysis. In the US, energy has accounted for one-third of defaults since 2000, and the figure rises to 45% since 2010 – a period that takes in the abrupt collapse in the oil price in 2014/15. A reminder that energy prices can fall as well as rise, even though it might not feel that way now.

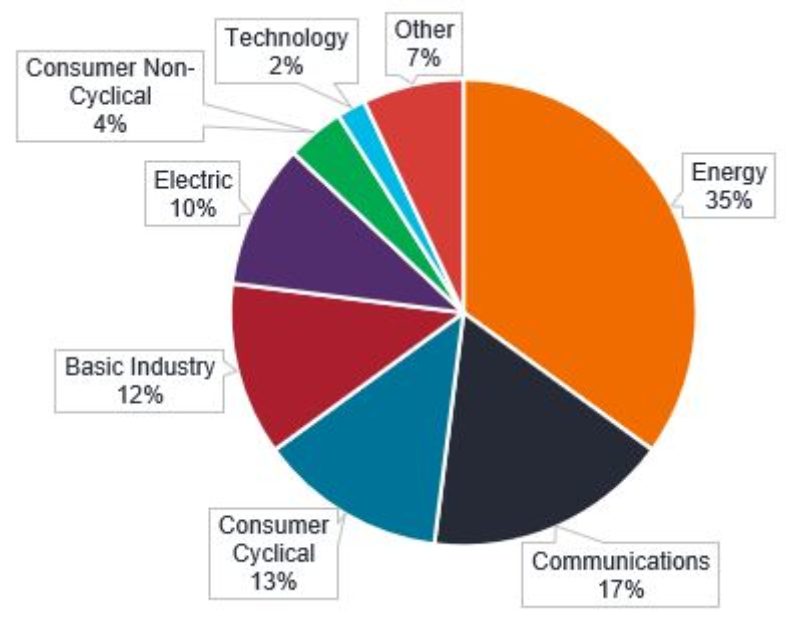

Figure 1: Look before you leap – sector weight of defaults in US since 2000

Source: Bloomberg, Barclays Research, 2000 to 2022, July 2022.

Note also that renewables typically become cheaper every year. The main area of cost lies in the total installed cost (equipment and installation) which has been trending down. The International Renewable Energy Agency, an intergovernmental body based in the oil-rich United Arab Emirates, reported that the cost of electricity globally from onshore wind in 2021 fell by 15% compared with a year earlier and was down by 13% in offshore wind and down by 13% in solar photovoltaics. Furthermore, almost two-thirds of renewable power generation added in 2021 had lower costs than the cheapest coal-fired options in G20 countries.2

These figures are important. Investment in green energy is not just an environmental nicety – it makes long-term financial sense. That is why it is important to differentiate between short-term shocks and the medium- to long-term investment case. The scramble for gas in Europe currently is predicated on national energy and security concerns brought about by the sudden reduction of gas supplies from Russia – which had been responsible for around 40% of the European Union’s gas imports prior to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.3 Substituting for that will take time but it is underway. In the very short term, that means finding alternative sources. Longer term, however, the solution to overseas gas dependency is through new technologies and having a varied domestic energy mix. Renewables offer the dual prize of energy independence with free fuel (wind, sun, and rain) and a greener economy.

The result of the gas supply shortages from Russia was equivalent to a carbon tax that was beyond the realms of anything the most ardent green lobbyist would have demanded. Governments are having to borrow heavily to offset the costs of the spike in energy prices. In the UK, the yield on 10-year gilts rose 11 basis points on 8 September when the energy price cap package was announced.4 To be fair, the general climate of monetary tightening by central banks (the European Central Bank (ECB) raised rates the same day) contributed to the rise, but some of the rise is likely to reflect worries about the heavier debt burden, with estimates from the Institute of Fiscal Studies that it could cost the government £100 billion in the first year alone. The cost is being internalised – more on that later.

One of the quickest ways to bring demand and supply into equilibrium when supply is constrained is simply to reduce demand. At its most extreme, this might involve rationing – something which is not inconceivable in Europe in coming months if a cold winter puts pressure on gas. But demand can also be reduced by being more efficient.

ESG is at the forefront of the drive for efficiency. Examples include better insulation or more efficient appliances within households, or in industry through robotics, and software as a service. The beauty of efficiency is that it helps bring down costs alongside benefiting the environment, which is a win-win for businesses and consumers.

ESG helps recognise externalities and the potential costs to companies that can arise from them. Here, it is important to remind ourselves that ESG is not solely about ‘E’. In fact, good ‘G’ (governance) has long been one of the key drivers of mitigating downside risk for investors. Are questionable board practices obscuring accounts and potentially hiding a fraud? Is a company’s sales model overly aggressive and potentially storing up liabilities in the future? Might fines or regulation become more punitive for polluting companies? In the UK, some water companies are facing potential credit downgrades as the scale of additional investment they face to tackle leaks and pollution comes on top of already high debt levels. ESG can help limit reputational risk. This has become increasingly important in an age of social media, where news is amplified, and a damaged reputation can prove very costly.

Failing to cost externalities, one could argue, led to the predicament Germany is facing in energy policy, the key one being heavy reliance on one key supplier (Russia).

For bondholders, risk reduction is instrumental in capturing the spread premium that borrowers offer as compensation for potential default. A company that cares for or helps mitigate its impact on the environment is likely to face fewer liabilities. The ECB is arguably taking the lead in recognising climate-related financial risk, expressing concern that climate change can lead to disruption that affects banks, and that banks could end up lending against stranded assets. Leading by example, from this October, the ECB is set to gradually move its €343 billion corporate bond portfolio away from carbon-intensive assets.5 Some might see this as an overreach of powers, but it is showing leadership in driving change.

In economics, the free-rider problem is a type of market failure in which those who benefit from resources, public goods or services do not pay for them or underpay. Pollution or climate change is a key example of this – where those who pollute or contribute to climate change do not always face the costs of their actions. As such, there can be little incentive to change until pressured to do so.

Regulatory intervention alone is not a solution. Societal pressure is a key driver of change (which should, in turn, be driving the need for governments and regulatory bodies to get involved). What might have seemed acceptable to previous generations becomes less so as opinions shift and scientific knowledge advances. Governments around the world are accepting the scientific evidence of climate change as rising global temperatures correlate with carbon-intensive energy use by humans.

The dominant role of humans in driving recent climate change is clear. The conclusion is based on a synthesis of information from multiple lines of evidence.

– Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change6

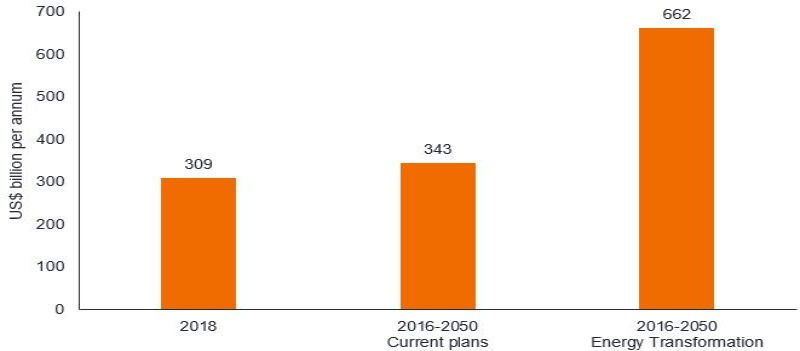

We are seeing this play out in net zero carbon commitments that are bound into law. Governments are instrumental in helping draft laws that can remove the free-rider problem by enshrining regulation and directing economies in paths that are more beneficial to society as a whole. These include the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 in the US that proposes US$375 billion to tackle climate change and the €806 billion Next Generation EU package that is structured to promote a green recovery. These initiatives alone amount to a massive investment opportunity and are just a part of the global annual investment required for energy transformation to net zero.

Figure 2: Energy transformation is an investment opportunity – global annual investment needs.

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency, April 2019.

Is there a moral dimension to ESG? Well, investors can choose where to invest. They can invest in portfolios with an ESG focus or invest elsewhere. Europe has led the way on ESG, perhaps helped by the fact that climate change, pollution, working conditions, and corporate governance are not limited to one country but affect several or all countries. Structurally, it has been easier through the combined European bodies to recognise shifting public opinion and legislate accordingly. Greater risk awareness and pricing of externalities mean the financial materiality of ESG risks is now more prevalent and investors are increasingly seeking portfolio managers who take this into consideration.

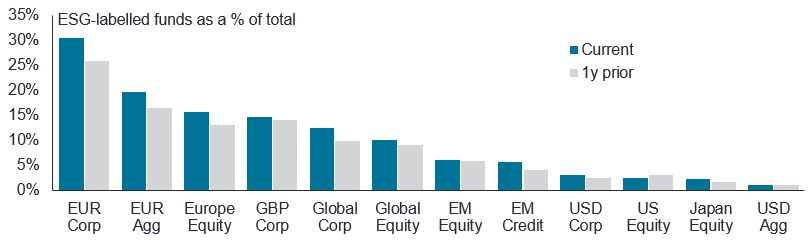

If we take a look at funds under management globally, ESG’s relevance in the broader investment universe has continued to grow. It now accounts for 30% of EUR corporate bond funds (see Figure 3), with the fastest growth in Emerging Market (EM) credit.

Figure 3: ESG-labelled fund assets as a percentage of total

Source: EPFR, Barclays Research. Based on monthly reporters, one-month lag. Based on fund AUM, 31 August 2022. Agg = Aggregate, representing funds that hold a broad base of debt securities, including government bonds, corporate credit, and asset backed securities.

Corporate issuers are responding to this demand, recognising that borrowing may be cheaper if it is linked to ESG or sustainability goals. The ‘greenium’ is the yield difference (spread) between a green bond and the estimated yield for an identical non-green bond. For much of the recent past, green bonds have traded with a negative greenium, i.e. their yields were lower than non-green bonds’, making it attractive to issue green bonds.

This can give rise to the temptation to ‘greenwash’; by this we mean borrowers making exaggerated or false environmental claims to help raise capital from investors. This threatens to undermine trust in ESG and lead to investors becoming sceptical of green bonds. Hence the importance attached to taxonomy and a push to move away from voluntary standards to more mandatory standards. This is already taking place at the investor level with ESG fund definitions and disclosure regulation becoming stricter through EU directives but bond issuance is still a grey area. The EU’s own standards have been seen as “sliding” as gas and nuclear have been allowed to be treated as green given their potential to help in the transition away from coal and towards energy independence.

Considering the varying quality of labelled bonds, this underpins the importance of focusing on assessing materiality of ESG risks for the company as a whole and the credibility of its management’s actions to mitigate them.

ESG factors have long been considered in informing investment decisions. In fixed income, in particular, where downside risk mitigation is at the core of investing, identification and understanding of elevated ESG risks are essential. It also aids in finding improving ESG stories, which, over time, should translate into a reduced cost of capital and the potential for better risk-adjusted returns.

Within Janus Henderson Fixed Income we recognise that this is not a sprint but a marathon. It must be ‘run’ consistently and be all-inclusive (rather than based on blanket exclusion of ‘dirtier’ sectors). We work with companies, through rigorous engagement, to help facilitate their transition towards more environmentally friendly business models, for example, encouraging fossil fuel companies to adopt carbon disclosure reporting, move to greener fuels or build carbon capture. After all, it can often be more efficient to repurpose existing capital and labour than to have to start from scratch.

There will likely always be occasions where taking a short-term tactical approach can pay off. ESG reveals its true results over the medium to long-term. The energy crisis has led to some near-term criticism of ESG but it is unlikely that the pendulum that has trended towards ESG is going to swing in the other direction. ESG can make a critical contribution in helping mitigate downside risks and the significant amounts of investment related to the net zero transmission alone mean it is not something to be overlooked.

[jh_content_filter spoke=”apac-social, arpa, auii, aupi, axii, bepa, brpa, clpa, cnpi-en, copa, deii, dkii, dkpa, dkpi, fiii, fipa, hkpi-en, iepa, iepi, lupa, lupi, media, mxpa, nlii, noii, nopa, nopi, pepa, ptpa, seii, sepa, sepi, sgpi, social, ukii, ukpa, ukpi, uopa, usii, uspa, uspi, uypa, zapa”]

[/jh_content_filter]

1 Source: OECD (2022), Gross insurance premiums (indicator), all countries, USD, total for 2020.

2 Source: IRENA, Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021, 13 July 2022.

3 Source: Eurostat database (Comext) and Eurostat estimates (April 2022), Extra-EU imports of natural gas by partner, % share, 2020 and 2021.

4 Source: Bloomberg, 10-year UK government bond yield, 8 September 2022.

5 Source: ECB, Corporate Securities Purchase Programme (CSPP) holdings at 16 September 2022.

6 Source: IPCC, Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Chapter 3, FAQ 3.1, 2021.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100th of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%

Credit risk: The risk that a borrower will default on its contractual obligations to investors, by failing to make the required debt payments. Anything that improves conditions for a company can help to lower credit risk.

Corporate bonds: A debt security issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due. The default rate is a measure of defaults over a set period as a proportion of debt originally issued.

Gilt: A UK government sterling denominated bond issued by the Debt Management Office (DMO) on behalf of HM Treasury. The term gilt (or gilt-edged) is a reference to the primary characteristic of gilts as an investment: their security.

High yield: A bond that has a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond. Sometimes known as a sub-investment grade bond. These bonds carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher coupon to compensate for the additional risk.

Inflation: The annual rate of change in prices, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

Investment grade: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments. The higher quality of these bonds is reflected in their higher credit ratings.

Net zero: Refers to greenhouse gas production being balanced by removal from the atmosphere.

Ratings/credit ratings: A score assigned to a borrower, based on their creditworthiness. It may apply to a government or company, or to one of their individual debts or financial obligations. An entity issuing investment grade bonds would typically have a higher credit rating than one issuing high yield bonds. The rating is usually given by credit rating agencies, such as Moodys and S&P Global Ratings. A downgrade refers to a bond or issuer moving to a lower rating, whereas an upgrade refers to a bond moving to a higher rating.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond this is calculated as the annual coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Actively managed portfolios may fail to produce the intended results. No investment strategy can ensure a profit or eliminate the risk of loss.

Derivatives can be more volatile and sensitive to economic or market changes than other investments, which could result in losses exceeding the original investment and magnified by leverage.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) or sustainable investing considers factors beyond traditional financial analysis. This may limit available investments and cause performance and exposures to differ from, and potentially be more concentrated in certain areas than, the broader market.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit, and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Securitized products, such as mortgage- and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed-income securities.