Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Portfolio Manager Jason England explains why Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Jerome Powell struck the right note when emphasizing the paramount importance of returning inflation to the Fed’s 2.0% target.

Many in the financial community tuned into Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Jerome Powell’s Jackson Hole speech on Friday to divine how large of a rate hike the central bank may deliver at its September meeting. What they got was something better. Rather than myopically focusing on the near term, the typically circumspect Fed Chair delivered a succinct and forceful reflection on the role of monetary policy in the economy and a history lesson on the greater pain brought to bear when a central bank loses focus on its overarching mission.

Mr. Powell minced no words as to what that mission is: Price stability is paramount, and the Fed’s immediate objective is to maintain its current hawkish stance until inflation returns to the central bank’s 2.0% target. He recognized that, in order to achieve this, the other half of the Fed’s dual mandate – full employment – would likely suffer. The impact of inflation on the labor market is complicated by the current imbalance between the supply and demand of workers. Yet, the existence of well-noted supply-side drivers of inflation – both labor shortages and lingering pandemic-related supply-chain dislocations – is no excuse for the Fed to not maintain laser focus on price stability. The Fed will continue to deploy the tools at its disposal – namely raising interest rates – which work by tamping down on demand in leverage-driven economy.

Chairman Powell has inserted into the conversation a needed reminder of why price stability is the bedrock of monetary policy. Persistent inflation distorts the price mechanism as it enters into the decision-making process of both businesses and households. Put another way, it makes an economy less efficient. When left unchecked, inflation can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, weigh on confidence by lowering the value of savings, and in extreme cases, lead to social unrest. Importantly, Mr. Powell noted that the ill effects of inflation disproportionately fall upon lower-wage workers and other vulnerable cohorts. Yet, as history has shown, the price of inaction only grows over time, and it’s necessary for the economy to swallow a smaller dose of bitter medicine now than a much more potent one down the road, which almost inevitably leads to recession.

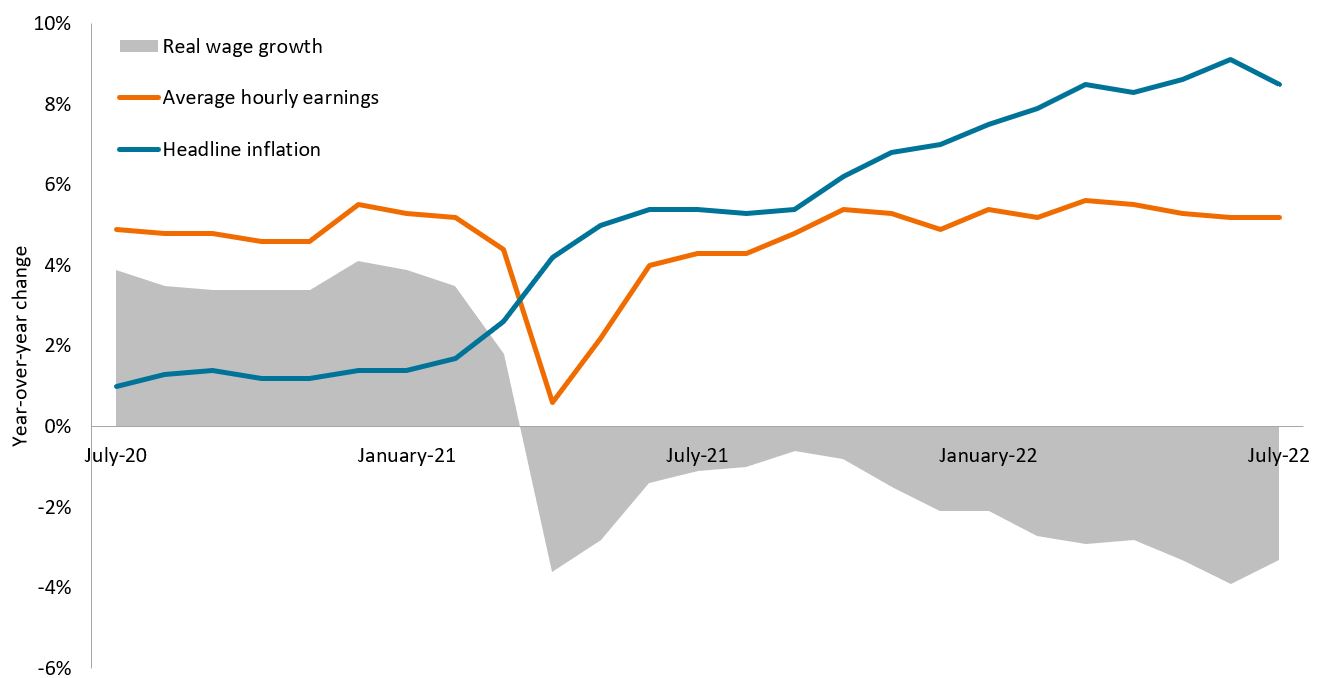

Unlike last year’s virtual Jackson Hole conclave, there was strong alignment among Fed officials at this year’s meeting, with even the doves recognizing the need to rein in generationally high inflation. The Fed famously touts that it is data driven, and the data indicate there is little choice other than maintaining a hawkish stance. The present gap between the headline consumer price index, which includes food and energy, and hourly wages is 3.3%. That means in real – i.e., inflation-adjusted – terms, the average American worker has received a pay cut of that magnitude over the past year.

Annual change in U.S. headline inflation, nominal and real wages

A measure of the ferocity of this bout of inflation is the degree to which real wage growth has turned negative, and the Fed will likely have to tighten until this gap is closed.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 28 August 2022.

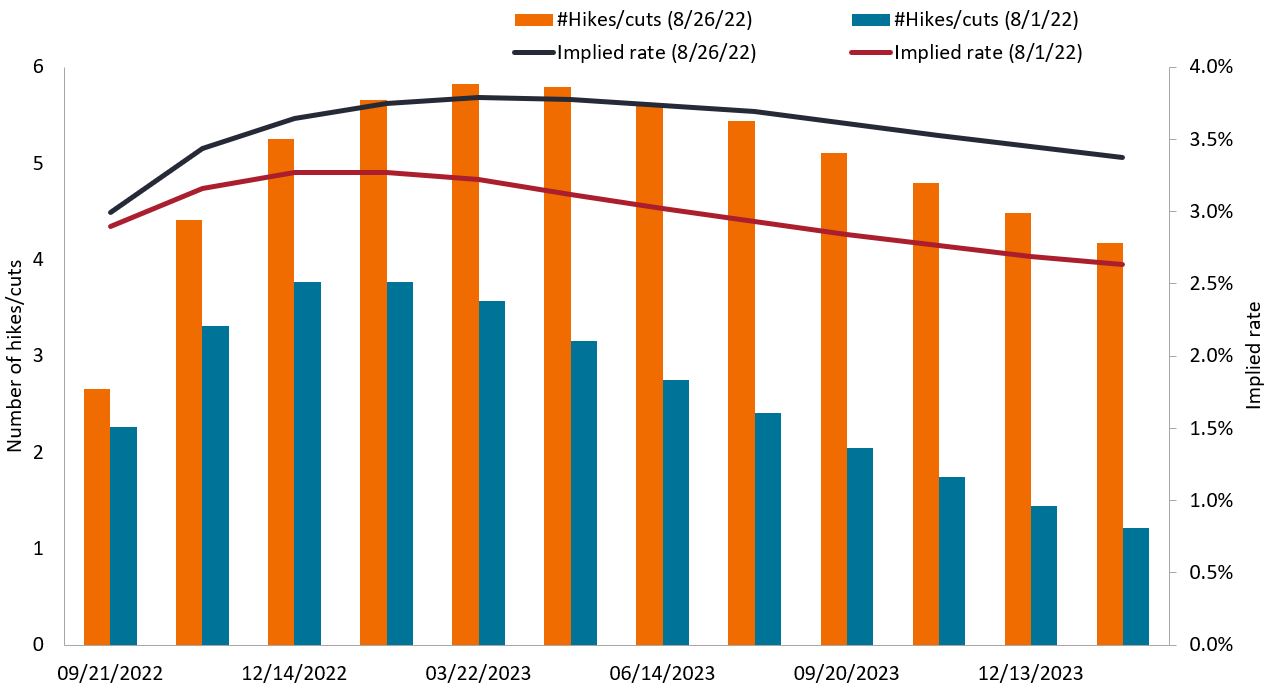

We believe that the Fed’s job won’t be completed until this gap is closed. Consequently, we’ve watched with a bit of amazement as futures markets hint that the Fed’s task will be an easy one. Only last week, futures prices were conveying the view that the Fed would not only stop raising rates by the second quarter of 2023 but also lower them only a couple of months later. Mr. Powell rejected the notion of such a pivot by referencing the Fed’s errors of the 1970s and early 1980s when it prematurely backed away from tightening. As stated, this only prolonged – and magnified – the problem until then Chairman Paul Volker took the draconian step of raising the overnight rate to 20.0% in 1980.

Number of 25-basis-point rate hikes and policy rate implied by futures markets

Over the past month – and especially this past week – futures markets have backed away from their prediction that the Fed’s task of reining in inflation would be completed by mid-2023.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 26 August 2022.

Chairman Powell emphasized that no such pivot would be forthcoming until inflation has been tamed. The price of this could be a sustained period of below-trend growth. We concur, as we believe the market has underestimated the task at hand. It will take time to narrow the gap between headline inflation and wage growth. And while that is an important barometer, so, too – paradoxically – is the health of the labor market. Job growth remains strong, with monthly payroll additions averaging 486,000 year to date. Yet in a service-based economy like that of the U.S., demand for labor is a key variable that the Fed can attempt to manage when seeking to lower upward price pressure. Other factors to watch are debt-intensive capital expenditure on the corporate side and home purchases with respect to consumers. Softening in these demand-side segments would also indicate that higher rates are achieving their desired effects.

As inflation raged earlier in the year, for a brief period the market and the Fed were in alignment in their view that rates must rise, and considerably, to quell accelerating prices. During this period, emphasis was placed on whether – or by how much – rates should exceed the Fed’s expected long-term neutral rate – that is, the rate that is neither inflationary nor weighs on labor markets. Only last December, Fed officials saw no need to raise rates above the 2.5% neutral expectation. Fast forward six months and the Fed’s June “Dots” survey indicated that the overnight rate was likely to remain well above 2.50% through 2024. Chairman Powell confirmed that view Friday.

Left unstated – and to be determined – is whether the neutral rate of 2.50% should be revisited. In a step that’s hard to reconcile with recent developments, March’s Dots survey actually saw the Fed’s median projection for the neutral rate slip to 2.375%, only to be revised back to 2.50% in June. Will it need to increase more? The answer lies in the Fed’s ability to tame inflation sooner rather than later.

The inflationary forces of deglobalization are not going away and neither are the disruptions to global food and energy markets brought on by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Closer to home, as long as real wages remain negative, workers will likely demand higher pay. All of this indicates the possibility that not only could the Fed Funds rate remain above 2.50% for the near term, but also that the central bank’s bogey for neutral may again rise.

Should that be the case, markets will finally have to become resigned to an era of higher nominal rates and ultimately a higher real cost of capital as the Fed keeps its sights set on price stability. As evidenced by the prices of riskier assets swooning in the wake of Chairman Powell’s speech, a scenario of the salad days’ extraordinarily accommodative policy emphatically being over will take some time to get used to.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an unmanaged index representing the rate of inflation of the U.S. consumer prices as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.