Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has announced its bid to tame inflation, but could tightening monetary policy at this point usher in different risks? Portfolio Manager Bethany Payne considers the ECB’s options.

The structural complexities of the eurozone have certainly resurfaced in recent weeks. Higher interest rate expectations have come hand in hand with wider spreads between German and peripheral government yields, triggering fears that the European Central Bank’s (ECB) narrow focus on tackling inflation risks the sustainability of peripheral debt.

The ECB called an emergency meeting on 15 June and announced accelerated efforts toward a tool to ensure that peripheral spreads remain contained, allowing the bank to raise interest rates as required. This has allayed some fears, but markets are suspicious of promises from a central bank that has regularly been stymied by the constraints of its mandate and underlying legal structure. The challenge of being focused solely on inflation while policy making for 19 divergent countries with different structural growth rates is not to be underestimated.

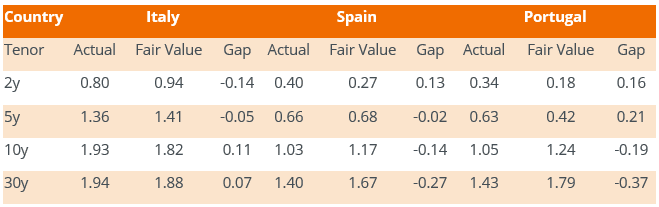

Source: Bloomberg, 22 June 2022.

Arguably, the ECB’s singular framework for price stability would demand higher bank rates regardless of employment levels – which would be inappropriate for some economies. This is a test of faith for the union and the ECB could quickly run into moral hazards. Unlike the Federal Reserve in the U.S., the ECB does not want to engineer a slowdown in demand to tackle inflation; its measured fiscal response to the pandemic also does not warrant it. Structural disinflationary forces such as technological progress and labor underutilization still prevail, and so therein lies a risk in going too far in policy action.

This is especially true considering the pandemic has increased the heterogeneity of the euro area. Inflation between countries is at its most varied since the 1990s, with energy the culprit (Figure 2). The ECB may have to hold its breath to lift the bank rate off the floor – knowing that to fight off supply-driven inflation like this is akin to pushing on string – while potentially weakening its own policy transmission across the bloc and increasing fragmentation risks. In other words, divergence between weaker and stronger economies.

Source: Bloomberg, 31 May 2022.

European bonds are not in the same fragile condition as they were during the sovereign debt crisis a decade ago, largely thanks to policies enacted at that time. European government debt has grown much more slowly than the U.S., reflecting treaties aimed at preserving the euro’s value. Nevertheless, indebtedness has risen since the crisis, mainly due to the unexpected burden of the pandemic.

Government deficits have increased during the COVID era and budget balances are at/below the negative 3% of GDP (Figure 3), but these are expected to improve as governments reduce pandemic-related spending. During a period of yield-suppressing quantitative easing (QE), worries of spiraling debt relative to the size of economies were not a concern. Without QE, however, as the ECB tapers its asset purchases, government deficits are not so easy to ignore. With the interest burden increasing, combined with higher inflation and stagnating growth, governments’ primary balances will be under pressure and a renewed focus will fall on fiscal sustainability.

Source: Bloomberg, 22 June 2022.

Rising debt and interest burdens feel alarming at a time of weakening growth. The ECB revised down real gross domestic product (GDP) growth expectations by 0.9% for 2022 and by 0.7% for 2023, to 2.8% and 2.1%, respectively.2 However, the cost to European taxpayers is still very low: servicing their debt fell to just $186 billion at the end of 2021, its lowest level in at least 25 years,3 thanks to very low interest rates. Most major European nations have also become more resilient over the pandemic by extending the average maturity of debt and consequently reducing refinancing risks (Figure 4).

When looking at debt sustainability, it is Italy that really stands out to us. The country’s debt rose $133 billion, or 4.6%, in 2021, reaching a record high.3 Not only is the debt pile significant and looks set to increase in 2022, but rate hikes would push the cost of Italy’s debt up significantly – and quicker than its peers.

Figure 4: Average Maturity of Debt on Offer

While most countries have increased the average maturity of debt on offer, half of Italy’s debt is still due in the next 5.5 years, compared to seven years in 2010. Italy is also behind on its funding this year, only completing 52% of debt issuance by the end of June, compared with 68% at the same point last year.4 While in our view a debt spiral is unlikely, 4% yields on Italy’s sovereign BTP (Buoni del Tesoro Poliennali) bonds demands strong budgetary discipline and positive primary balances. According to NatWest, Italy will need a 0.7% primary surplus if average funding costs are at 3.5% (Figure 5) to achieve debt stability.

Source: Bloomberg, 7 May 2022. The 0.7% level is what is required if the average interest rate is at 3.5%, NatWest 6 May 2022.

As a measure of debt costs, the effective cost on Italian debt is low at 1.5% due to QE and negative interest rates (compared to an average of 2.5%5). If the cost of servicing debt rises and the economic environment deteriorates, then Italy could look fragile again. This would be worrying, especially going into the election in 2023, given populism risks.

The emergency ECB meeting was called only a week after its scheduled one, where the bank decided only to guide on multiple rate hikes in future. The speed in rates increasing, spreads widening and perceived weakness in Italy probably pre-empted this decision, supporting our view that the ECB is likely to be proactive rather than reactive from here on out, and that a new backstop is close to being announced.

ECB Governing Council member Isabel Schnabel suggested that the backstop will be used to prevent non-fundamental fragmentation risk (such as sentiment) rather than spread widening based on fundamental weakness. Debt sustainability (a fundamental) is thus still important as fundamental spread widening will be tolerated. Reports suggest ECB President Christine Lagarde told Euro-area finance ministers that the ECB’s new backstop will be triggered if borrowing costs rise too far or too fast. Some widening will be tolerated then, but no precise interest rate or spread targets have been, or likely will be, disclosed. No one in the Governing Council will object to a commitment to safeguard the policy transmission mechanism – the process through which monetary policy decisions affect the economy in general and the price level in particular – and prevent fragmentation. However, when and how such a backstop should be activated could likely be very controversial, with serious legal and operational challenges to overcome. The hurdle to launching anything concrete might be high.

The last time fragmentation risks were acute was during the sovereign debt crisis, where ECB President Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech was followed by an announcement of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs), or unlimited asset purchases. The pledge itself was enough to contain peripheral spreads. While Lagarde has repeated many times that the ECB has the bloc’s back and is ready to do whatever is needed to avoid fragmentation, she is unlikely to get by so easily.

Unlike in 2010-2012 when the ECB stepped up, increasing its balance sheet by 67%6 as fragmentation risks increased, the paradox now is that QE is coming to an end and the net effect of its reversal works in the opposite direction. The backstop is therefore more crucial and needs to be credible so that markets do not unduly test Lagarde’s resolve.

To properly gauge the scale of the challenge, the ECB has bought more than €4.9 trillion of bonds, equivalent to more than a third of the eurozone’s GDP, since launching QE. Over two years, it has bought more than all the extra bonds issued by the eurozone’s 19 governments,7 giving it vast sway over borrowing costs in the region. The ECB has also been slower to slow/end its bond purchases than most western central banks.

Part of these purchases have been through the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) – a limited, but unconditional program to buy bonds in response to pandemic-related stresses. Now that ECB asset purchases are ceasing at the end of June, all that remains is the reinvestments of maturing bonds in the programs, which for the PEPP continues until at least the end of 2024.

The ECB is making use of these reinvestments. At the June meeting, it announced further flexibility under PEPP to help with fragmentation risk. This could entail pulling forward future cash inflows from maturing bonds and investing these flows within the eurozone. It could be a form of German bund quantitative tightening, or QT, transferring purchases from northern to southern European countries. This could be worth around €200 billion8 a year of bond maturities brought forward.

For context, if the proportion of purchased bonds among eurozone countries were the same as seen before during this program, a conservative estimate of PEPP would be equivalent to funding 11% of Italy’s new debt issuance this year. Given the flexibility of the program, it is almost certain that PEPP reinvestments may account for more than this, but in comparison, PEPP bought nearly half of all Italian issuance in 20219.

While PEPP purchases have been more effective in times of stress and will be the first responder to help deal with peripheral spread crises, PEPP flexibility is only a partial solution to solvency and liquidity concerns. The advantage of using PEPP is the lack of conditions, helping to avoid fiscal restraint in response to what is, essentially, an external shock. The program is limited, however, and a backstop, to be credible, should arguably be unlimited. The bigger the bazooka, the less it is tested and therefore required.

For context, it is important to note that OMTs were unlimited and the program still exists, but they impose conditionality upon nations, forcing a tightening of budgets. Similar conditionality is likely to be unappealing this time around, making it effective only when stresses have built almost to the point of no return. Clearly this is not what the ECB is seeking to achieve.

We believe the central bank will need to structure a backstop that will be considered effective, but which avoids contravening ECB legal rule around monetary financing, or else it risks being challenged in the German constitutional court. This could be where the NextGenerationEU (NGEU) framework may be helpful.

NGEU is a cornerstone of Europe’s response to the pandemic, supporting the recovery by offering financial support to EU member states on the condition of specific investment and reform projects. This framework is a type of surveillance system, engendering growth and economic convergence across Europe. Marrying this framework with a new unlimited OMT could enable the ECB to keep its balance sheet contained while supporting the growth and integration of the eurozone. It could help spreads to converge and therefore help to limit downside risks.

How close are we to the ECB acting? The 10-year yield on Italy’s sovereign debt has shot up by 2.46% this year, while 10-year German yields surged some 1.87%, escaping negative territory. When you consider that Italy is higher-beta debt, the jump and consequent wider spread is pretty much in line with what our proprietary models suggest (Figure 6), indicating that there could be further stress to come.

Figure 6: Peripheral Sovereign Debt Spread over the German Bund Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 22 June 2022.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 22 June 2022.

The extraordinary ECB meeting on 15 June suggests to us that the bank may be preparing to be more proactive than reactive in its efforts to tackle unwarranted market stress, paving the way for sustainable interest rate hikes from here. As we expect the ECB to raise interest rates by 0.25% in July and possibly again in September, we believe a generous backstop should be announced in July. If so, it will add pressure to German bund yields, but keep peripheral risk premiums suppressed.

However, the conflict in Ukraine is first and foremost on everyone’s minds and is affecting the fiscal outlook across governments. Germany, for example, has abruptly changed its policy on defense spending, committing to reach NATO’s target of 2% and continued to abandon its debt brake.10 The question of energy security may also need to be answered with significant investment. Such fiscal pressures are likely to confront all western governments to varying degrees in the years ahead, too. It is thus conceivable that another round of QE may even become necessary at some point.

1 Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece are Europe’s peripheral countries.