March 2021 Global Bonds

Rising bond yields — a validation of recovery or a challenge?

Andrew Mulliner, CFA

Andrew Mulliner, CFA

Head of Global Aggregate Strategies | Portfolio Manager

March 2021 Global Bonds

Rising bond yields — a validation of recovery or a challenge?

Andrew Mulliner, CFA

Andrew Mulliner, CFA

Head of Global Aggregate Strategies | Portfolio Manager

The world is set for a strong cyclical recovery. Andrew Mulliner, Head of Global Aggregate Strategies, shares his thoughts on the divergence in economic fortunes that are beginning to appear and the likely impact on investment opportunities.

Key Takeaways

- As global bond yields have moved higher, notable divergences begin to appear among regions and countries; central bank responses have also been diverse, in stark contrast to the unified response in 2020.

- Disentangling what should be temporary growth uplifts from longer term structural dynamics will be somewhat challenging.

- Recognising the dynamics at work is crucial to understanding whether today’s higher yields represent an opportunity for bond investors or whether the 30‑year bond bull market is over.

The world appears to be set for the strongest cyclical recovery since the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Accompanying this rosy outlook has been a pickup in global bond yields, albeit from extremely low levels. That yields are rising should be of little surprise to investors. In the recovery phase of the economic cycle, we would expect yield curves to steepen. Yields on longer dated bonds rise as investors reassess the outlook for long‑term growth while those on shorter dated bonds remain low, as central banks hold rates at low levels, cementing the economic recovery and encouraging economic actors to borrow and invest.

However, while global bond yields have moved higher in the past six months, there are notable divergences among regions and countries, both in terms of the strength of the economic outlook and the degree to which the changes in bond yields represent a validation of recovery or a challenge. Figure 1 shows gross domestic product (GDP) levels relative to end 2019 for a number of countries over the next two years.

Figure 1: Consensus GDP forecasts relative to 2019

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 11 February 2021.

Note: Chart depicts levels of gross domestic product (GDP) relative to end 2019 level, based on Bloomberg consensus forecasts.

Understanding the divergences and their likely impact can have a significant effect on the investment opportunities we see evolving in global bonds.

Diverse central bank responses to rising bond yields

In Europe, rising nominal bond yields, even when those yields remain negative, has resulted in strong verbal and actual intervention to limit and potentially even reverse the moves. In the US, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has reiterated its very dovish stance verbally but left its policy measures unchanged, and if anything, warmly welcomed the significant lift in bond yields as validation of the effectiveness of its policy measures. Other markets such as Australia, which was at the vanguard of the move to higher yields, have also pushed back on market pricing of yields but specifically around the timing at which the central bank is expected to lift rates, rather than the overall level of yields.

This diverse set of central bank responses to the move higher in yields stands in stark contrast to the unified responses of 2020 when rate cuts and quantitative easing programmes were common policy measures. The reasons for this are many but can be principally disentangled into the starting point for the different economies prior to the pandemic, how the economies weather the storm and the nature of the measures.

First a look at Europe

When looking at economies through a more structural lens, the challenges of today’s higher yields become more apparent. Taking Europe as a prime example, with anaemic growth and inflation already a chronic problem, the coronavirus pandemic has resulted in major falls in growth and significant increases in public debt loads, as governments have responded aggressively to avoid economic disaster.

Both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Union (EU) have taken significant steps to support the system, via bond purchases in the case of the ECB, and the launch of the next generation EU funds, which represent the first major foray into mutualised European debt issuance. The capital raised is to fund a combination of grants and low-cost loans to the hardest hit countries of the EU to assist in the recovery from the pandemic.

While the introduction of these schemes are significant for Europe, they are responses to a crisis and do little to solve the chronic issues that Europe continues to face. The baseline situation of weak growth and inflation continues to represent the biggest challenge to policymakers and although economic growth is expected to recover strongly, the ECB is all too aware that cyclical recovery is not enough, and that higher bond yields represent a tightening of conditions that Europe can ill afford.

Australia next

Australia has weathered the coronavirus pandemic better than most developed economies. It acted swiftly to clamp down on the virus by shutting its borders on 20 March 2020 and strictly enforced its border security. This resulted in a domestic economy that bounced back quickly as internal restrictions were lifted relatively fast, even though sectors such as tourism remain significantly impacted. Also, as an exporter of raw materials such as iron ore and being economically sensitive to Asian and Chinese growth, Australia’s chief export sector has been a beneficiary of the global shift away from services to goods.

Given the virus seems to have a seasonal element to it – colder temperatures correlating with higher transmission, the transition to the cooler winter period in Australia in the coming months could pose the risk of an increase in transmission. However, strong border protections and few if any cases in the country, should mitigate this risk.

All of this might leave us to expect that Australia’s outlook is bright, and to some extent it is; however, with the winter season approaching, government support measures rolling off and vaccination a second half of 2021 event at best, the Australian economy faces arguably more headwinds to growth this year compared to the likes of the US.

It should also be remembered that prior to the pandemic, Australia was already in a slowing growth regime with low wage inflation and an economy still coming to terms with the tailing off of the massive

investment boom in the mining sector that China’s spectacular economic emergence prompted. In a world where relative rates of change matter, Australia is likely to appear something of a laggard in 2021 and with plenty of the previous challenges still to be faced.

It would be remiss to ignore the Chinese economy

China emerged from 2020 with a positive growth of 2.3% in spite of being the first country impacted by the virus and having some of the strictest lockdowns imposed around the world. After the first quarter of 2020, the economy reopened, albeit with a focus on the ‘old style manufacturing’ rather than service sectors. The country benefited from its key role in the global supply chain for medicines, personal protective items (PPI) and much of the manufactured goods that were increasingly demanded in western economies more traditionally focused on service sectors.

China is also noteworthy for its moderate monetary policy response, with the authorities focusing their attention on fiscal measures for specific elements of the economy. As other economies took interest rates down to zero and engaged in massive quantitative easing, the People’s Bank of China cut its 1-year loan prime rate by only 35 basis points from 4.15% to 3.85% while managing liquidity actively in the system, as they sought to contain the crisis and at the same time avoid a speculative boom in housing – something they have been keenly focused on for some years.

Do not look to China to reflate the world

Hopes of a repeat of the post 2008 China investment boom, which drove much of the global recovery after the financial crisis, are likely misplaced this time around. China has no intention of reflating the world and the recent growth target of over 6% for 2022 (announced at the recent National People’s Congress) was lower than many anticipated, especially given the low growth rate of the previous year.

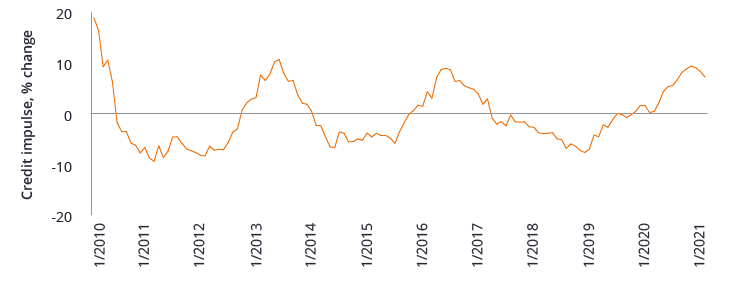

Looking further ahead, macroeconomic indicators such as China’s credit impulse (a gauge of the flow of credit), which has been a good leading indicator of the global economic outlook (by around 12 months), deserves attention (Figure 2). We see the credit impulse as rolling over, suggesting tougher times ahead for the global economy coming into 2022, where a negative base effect from this year’s fiscal stimulus will act as a brake on growth.

Figure 2: China’s credit impulse is rolling over

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 January 2021.

Note: 12-month percentage change in the China credit impulse, measured as growth in new lending/credit divided by nominal GDP, monthly data.

Challenges and opportunities ahead

This multi‑polar world represents significant challenges as well as opportunities for investors. Historically, cyclical recoveries have been accompanied by booming stock markets, tightening credit spreads and a weaker US dollar, as central banks provided accommodative policies, corporates repaired their balance sheets and earnings improved.

Already, the expectation for a weaker US dollar has begun to falter with an uncertain outlook ahead, as unprecedented US fiscal stimulus looks likely to drive US growth to the very top of the pile for 2021. US exceptionalism once again appears to be back, but with it comes a challenge to the weak dollar playbook that has so often been a boon to emerging market (EM) countries who often finance in this currency. For emerging market economies who are well behind in the vaccine rollout, a stronger US dollar potentially spells trouble for the durability of their recovery.

The true challenge for investors is working out whether the secular trends of the last decade – low inflation and moderate growth, will be overturned by the massive response to the pandemic. Both in terms of the accelerated embrace in technology and the billions poured into revolutionary vaccine programmes, but also the massive accumulation of debt on both public and corporate balance sheets.

A millstone around the neck of the bond markets?

History suggests that such massive debt burdens and the diminishing marginal productivity of debt will hang like a millstone around the neck of the bond markets, keeping yields low. There are also indications that the trend of lower fertility rates in wealthy countries has been significantly exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. This accelerates the trend of ageing populations and with it the questions as to whether ageing populations are inflationary or deflationary. While arguments are made in both directions, we find that evidence from Japan shows demographic decline correlates with lower yields and low inflation.

Against this, are expectations that massive fiscal responses in the western world and particularly in the US could finally see economies reach ‘escape velocity’ with growth and inflation rates back into the realms last seen in the 1990s. However, while stimulus has been large, so far only limited amounts seem destined for the sort of investment that could truly increase the productive capacity of these economies allowing for a sustained rise in yields through time. This suggests that once the sugar high of stimulus charged cyclical recovery has past, the global economy will look less different than one might have expected.

Investing in a turbulent world

How does one invest in a world of such turbulence with yields moving higher and the outlook beyond the next 12 months so shrouded in uncertainty? A nuanced approach to the traditional cyclical strategies seems appropriate. There are areas that could offer value such as higher yielding corporate debt and emerging markets, though we are cautious about treating the latter as a monolithic entity and only see value in select local markets and hard currency corporate bonds.

In government markets, we see increasing value as yields have risen. Beyond the US, there are significantly different opportunities for investors. In Europe we anticipate a continuation of the low yield, low volatility world that bond investors have become accustomed to and expect that strategies that benefit from stable rates to perform well.

Among countries that have experienced a significant rise in yields, there may be opportunities as market expectations have run increasingly ahead of central bank guidance in the normalisation of rates. This is particularly the case in Australia, which faces a more challenging environment in the coming ten years relative to the previous decade.

Additionally, many of these markets (the US included) now offer much higher yields (after currency hedging), compared to what is available in Japan and Europe, encouraging greater demand from overseas buyers (Figure 3).

Figure 3: 10-year hedged yields for a Japan-based investor

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 16 March 2021.

Note: 10-year government bond yields hedged to Japanese yen using 3-month forward cross currency rates, annualised.

Conclusion

The coronavirus shock to the global economy, a true exogenous shock that would have been hard to predict, represents one of the most significant economic disruptions in the history of the global economy, akin to a global natural disaster. The extreme nature of the economic drawdown and recovery, as well as the rapid progression through recession to recovery, makes disentangling what should be temporary growth uplifts from longer term structural dynamics somewhat challenging. However, recognising these dynamics is crucial to understanding whether today’s higher yields represent an opportunity for bond investors or whether the 30‑year bond bull market is over.

Featured Funds

JGBIX

Global Bond Fund

JGBDX

Global Bond Fund

Credit impulse: A measure of the change in the growth rate of aggregate credit as a percentage of gross domestic product.

Currency hedge: A transaction that aims to protect the value of a position from unwanted moves in foreign exchange rates. This is done by using derivatives.

Deflation: A decrease in the price of goods and services across the economy, usually indicating that the economy is weakening. The opposite of inflation.

Fiscal policy/stimulus: Government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. It is separate from monetary policy, which is typically set by a central bank. Fiscal expansion (or ‘stimulus’) refers to an increase in government spending and/or a reduction in taxes. Fiscal austerity refers to raising taxes and/or cutting spending in an attempt to reduce government debt.

Inflation: The rate at which the prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. The CPI and RPI are two common measures. The opposite of deflation.

Monetary policy/stimulus: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money. See also fiscal policy.

Nominal value: A value which has not been adjusted for inflation. Within fixed income investing it refers to a bond’s par value rather than its current (‘market’) value.

Quantitative easing: Monetary policy used by central banks to stimulate the economy by boosting the amount of overall money in the banking system.

Reflation: Government policies intended to stimulate an economy and promote inflation.

Spread/Credit Spread: The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. It is used as a measure of the riskiness of an investment.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

Yield curve: A graph that plots the yields of similar quality bonds against their maturities. In a normal/upward sloping yield curve, longer maturity bond yields are higher than short-term bond yields. A yield curve can signal market expectations about a country’s economic direction.