Knowledge. Shared Blog

November 2020

A Mostly Benign Outlook for U.S. Inflation

Jim Cielinski, CFA

Jim Cielinski, CFA

Global Head of Fixed Income

The stabilization of U.S. economic growth amid unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus has raised questions about the likelihood of inflation returning. Global Head of Fixed Income Jim Cielinski explains why he does not see significant risk of sustained higher inflation materializing in the next few years – but cautions that short-term spikes are possible and that investors should evaluate the diversification that their fixed income portfolios provide.

Key Takeaways

- Inflation has long been a negligible concern, but investors are now wondering whether historic fiscal and monetary stimulus could result in a return of inflation.

- In our view, significantly higher inflation is unlikely to materialize in the next few years as it will take time for unemployment to fall and demand for goods and services to exceed supply. In fact, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) is not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022.

- However, short-term rises in inflation are more likely. With low U.S. Treasury yields providing little compensation for the associated risks, investors should focus on realizing income and diversifying their fixed income portfolios.

For most investors, inflation has long been a negligible concern. For over two decades, the U.S. consumer price index (CPI) has wobbled around the 2% level, and the few significant deviations from that range were not surges in inflation but collapses. CPI hit its first new multi-decade low in 2003, falling to ~1% soon after the first of the two “Bush recessions.” About 10 years later it collapsed again, to ~0.6%, as the effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) worked its way through the real economy. The decade since has been dominated by global central banks not trying to combat inflation but trying to fuel their economies by lowering interest rates toward, or through, zero.

The unexpected shock of COVID-19 prompted the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) to return its official policy rate to zero for the second time this century (the first was during the GFC) as CPI plummeted from ~2.4% to 1.2%. Across the developed world, central banks initiated unprecedented quantitative easing – the direct purchasing of bonds to provide companies credit and put more money into the real economy. And, aware that it had struggled to meet its inflation target for some time, the Fed announced in August that it would shift its 2% inflation target to a long-term average of 2%. The subtle distinction confirmed that the Fed did not intend to raise interest rates again if it looked like inflation might rise to 2%, but instead would wait until inflation actually reached that level or even slightly above it. In short, the Fed’s message was that it wants to see higher inflation.

Meanwhile, governments have been enacting similarly unprecedented “stimulus” programs by spending trillions of dollars in their domestic economies. As economies have begun to stabilize, investors have increasingly started to wonder: Where is all this money going to end up? Will massive quantitative easing and historic fiscal spending result in a return of inflation?

Will Inflation Rise Meaningfully?

Aggressive fiscal policy, low global interest rates, an emerging economic recovery and the Fed telling us they will keep monetary policy accommodative until inflation actually rises all suggest that it will eventually rise. But in our view, while significantly higher global long-term inflation is certainly a risk, it is not a certainty.

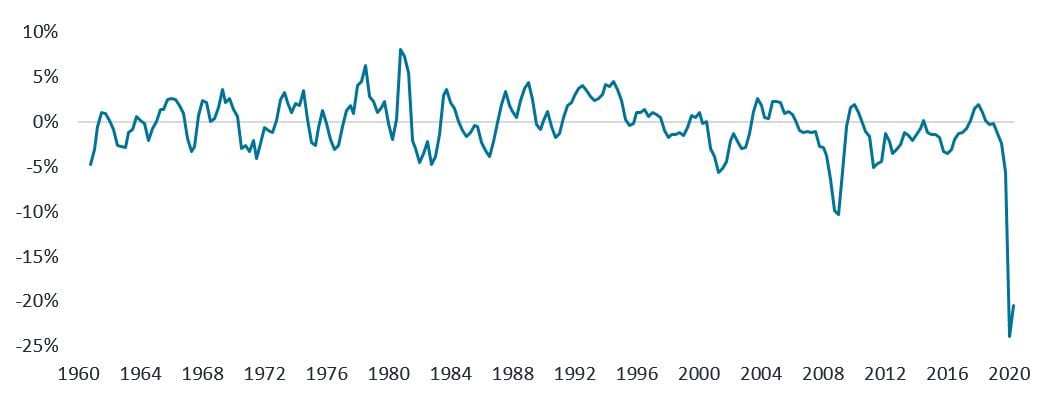

While it is true that money supply has surged globally (registering the fastest growth since World War II), how that money moves through the economy is as important as the amount. The chart below shows both the growth in money and its velocity (i.e., how fast that money multiplies through the economy). To get large spikes in inflation (for example, the sustained rapid growth America saw in the 1970s), economies need both easy money and the demand for that money to exceed supply for a long time. But today’s low velocity of money signals low demand for money.

Money Supply (4Q Change)

Money Velocity (4Q Change)

[caption id=”attachment_330259″ align=”alignnone” width=”1050″] Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 July 2020. Note: Money refers to M2 which includes cash, deposits and money market accounts. Money velocity is represented by the Velocity of Money Index (VELOM2)[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 July 2020. Note: Money refers to M2 which includes cash, deposits and money market accounts. Money velocity is represented by the Velocity of Money Index (VELOM2)[/caption]

If the increased supply of money were to start moving faster through the economy, the risk of inflation would rise. But creating demand for money, perhaps counterintuitively, is not as easy as creating its supply. The Fed can, with relative ease, cut interest rates and boost money supply. But creating demand for money requires a broad expectation that borrowing it, and investing it, will pay off.

The global economy has recovered from the lows set in the first half of the year, but there is still vastly more supply of, than demand for, goods and services across the developed world. The challenge is made harder by the fact that the current recession is among the most globally coordinated downturns in history: The exogenous shock of COVID-19 hit the economies of the world simultaneously and the worldwide output gap that shock created is large. Global unemployment is also high, reducing the kind of cost-pressure you can get when unemployment is low. We think significant price pressures are unlikely until unemployment gets back to pre-pandemic levels, and while employment is recovering, it has a long way to go.

In our view, confidence in the global economy will grow as treatments and vaccines for the COVID-19 virus are developed. But even with optimistic scenarios for vaccine distribution, it will take a few years of strong economic growth to close the gap between supply and demand. Of the world’s major economies, only China is expected to fully recover, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), before the end of next year. The U.S. economy is not expected to get back to pre-pandemic levels until 2022, and Europe not until between 2022 and 2025.1

A Modest Rise in Inflation Is Likely

While we do not see the economic conditions for sustained higher inflation globally, we do expect inflation could see periodic increases. The shock to the global economy has been severe and there are individual sectors and situations where supply disruptions could result in some higher inflation. Additionally, governments will have to navigate the handing off of fiscal stimulus to private-sector growth and the timing will not be perfect. Authorities, including the central banks, are more likely to be generous than cautious, creating the possibility of excess stimulus for fear of creating too little.

We believe U.S. lawmakers will continue to pass additional fiscal stimulus to help revive economic growth as long as the COVID-19 pandemic persists. However, after the U.S. election, the size of that spending could be more modest than the market was anticipating. Currently, $1 trillion over the next few years is now considered more likely than the projected $2 to $3 trillion forecast had the Democratic Party taken control of Congress and the presidency. But in our view, the rate of change in stimulus is more important than the headline numbers. Indeed, if there was no additional stimulus for the remainder of the year, the existing programs that have begun to roll off could create a significantly negative rate of change, depressing recovery and thus inflation.

Ultimately, we expect U.S. CPI could reach 2% to 2.5% in the first half of next year, not far from where it was before the pandemic. While such a figure would be a significant increase from current levels, we see it as a one-off “step” higher: CPI is quoted as a year-on-year percent change, and the 2020 base is low, whether because of the (albeit brief) negative oil prices in early 2020 or the broader collapse in demand for goods and services. As such, headline inflation is likely to be higher year-on-year into 2021, but this should not be confused with a regime shift to higher inflation.

A Little Inflation Reduces the Bigger Risk of Deflation

Policy rates, globally, have been trending lower for decades. And yet a level of rates that can succeed in creating sustained credit demand hasn’t been found. If the current recovery in Europe and the U.S. can’t become self-sustaining – if there isn’t a monetary policy accommodative enough to allow for that – secular stagnation throughout Japan, Europe and the U.S. would then become a larger concern with an unclear solution.

The alternative – some inflation – would go a long way toward reassuring central banks and the market that long-term economic growth is not at risk of stagnating. More practically, zero and negative interest rates limit central banks’ ability to manage their economies through monetary policy. Thus, some inflation, together with positive real rates (i.e., rates after considering expected inflation), would be welcomed by central banks. This is particularly true outside of the U.S., as long-standing disinflationary forces are more entrenched in Europe and Japan.

What We Are Watching

For inflation to become a larger concern, we need to see evidence of sustained credit demand. A good indicator of this is the velocity of money indicator shown in the chart above. A reversal in money velocity would signal an increase in credit demand, suggesting that the economy might be on a path to self-sufficiency, falling unemployment and, eventually, inflation.

Another, albeit less likely, indicator of rising inflation risks is political. The U.S. election looks most likely to result in the political parties sharing control over economic policy, with a Republican-controlled Senate limiting Democrats’ ability to spend. However, it remains possible that the Democratic Party gains control of the Senate and embraces a view that low interest rates are a consequence-free way to spend. Should the market begin to suspect an abandonment of fiscal responsibility, it could begin to price in higher inflation expectations.

Portfolio Positioning in a Low-Yield, Modest-Inflation World

As it will take time to close the gap between supply and demand, and the Fed will likely want to see the gap turn negative before raising interest rates, we expect monetary policy will stay accommodative until it does. Normally, the intent to create higher inflation would put pressure on longer maturity interest rates, and we do think the 10-year U.S. Treasury note is likely to reach 1% (it nearly got there this week) as the economy, and inflation, recovers. But we expect significantly higher levels are unlikely given the Fed’s use of longer-term rates to stimulate the economy, striving to keep them contained to help support the demand for credit markets.

However, higher yields are possible. If the Democrats take control of the U.S. Senate, for example, the markets could be spooked, which we might expect to push 10-year yields toward the 1.25% to 1.5% range. As such, we think investors should carefully consider their exposure to rising interest rates. The absolute level of U.S. Treasury yields is not only historically low but also provides little compensation for the risks of rising inflation – or rising yields, regardless of the cause.

In our view, investors should redouble their focus on realizing income and achieving diversity. Floating-rate exposure or instruments like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) could help hedge interest rate risk. Credit markets, including corporate bond markets and securitized sectors like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), could flourish in an environment where inflation is modestly higher and the demand for yield remains strong. While the duration of corporate bonds is relatively high by historical standards, combining these exposures with other lower-duration fixed income products could result in more attractive risk-adjusted portfolios.

1Deutsche Bank, Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, as at October 2020

Sources: Unless otherwise noted, all figures are from Bloomberg as of 6 November 2020.

The example provided is hypothetical and used for illustrative purposes only.

Knowledge. Shared

Blog

Back to all Blog Posts

Subscribe for relevant insights delivered straight to your inbox