Knowledge. Shared Blog

October 2020

Q4 Multi-Asset Outlook: Into the Fog of Uncertainty

-

Paul O’Connor

Paul O’Connor

Head of Multi-Asset | Portfolio Manager

What visibility is there for investors right now? Paul O’Connor, Head of the UK-based Multi-Asset Team, looks ahead to the fourth quarter of 2020 and beyond, summarizing his latest thoughts on COVID-19, Brexit and the upcoming U.S election.

Key Takeaways

- Investor confidence has been buoyed by encouraging developments on the economic recovery, policy and COVID-19 fronts, but there are a range of potential catalysts that could quickly push investor risk appetite in either direction.

- Major central banks are now reaching the limits of their current toolkits. If growth or inflation disappoint from here, fiscal policy will have to take more responsibility for stimulating the economy than it has done during the past decade.

- A gradual trend toward “normal” behavior could be a central theme for financial markets in 2021, but investors may have to endure some shocks before they embrace this theme and its positive reflationary implications.

While multi-asset investors could seemingly do no wrong in the early weeks of Q3 in an environment of surging equities, credit and most other assets, investing conditions became more challenging toward the end of the quarter, with many market uptrends rolling over in September. Of course, some market consolidation was probably overdue, after the unusually strong and broad rebound across asset classes from the lows we saw in March. Still, there were also some fundamental developments that rationalized this change in the mood of the markets as the quarter progressed. Investor confidence was buoyed by encouraging developments on the economic recovery, policy and COVID-19 fronts around the middle of the year, but the outlook in each of these areas became more complicated and uncertain as the third quarter came to an end.

A Bounce, Not a Boom

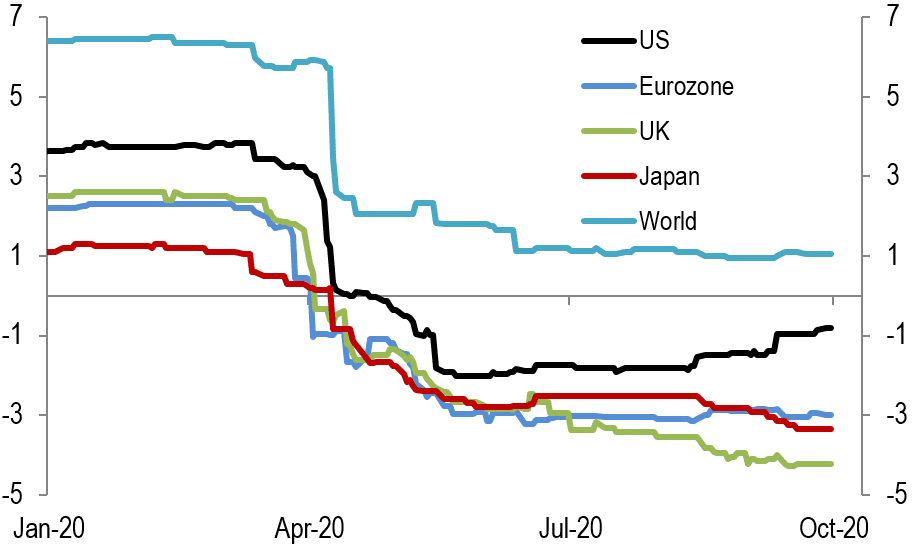

Economic data in recent months have shown the most dramatic and synchronized global growth rebound ever seen. This strong recovery is expected to carry on well into 2021. However, in broad terms, the upswing has only evolved in line with prior expectations: consensus forecasts for global growth across the two years 2020 and 2021 have been pretty stable for the past few months (see Exhibit 1), with small upgrades to China and small downgrades to most developed economies.

Furthermore, while headline 2021 growth numbers are likely to look strong, this will nevertheless be a partial rebound from a deep slump, not an economic boom. The damage from the COVID-19 shock will take years to repair. Economic activity in most of the major developed economies is unlikely to reach pre-pandemic levels until 2022 at the earliest. Unemployment is likely to be rising in many countries well into next year and falling only slowly after that.

Exhibit 1: Consensus Forecasts for Real GDP Growth Across 2020 and 2021 (%)

[caption id=”attachment_323111″ align=”alignnone” width=”650″] Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 30 September 2020.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 30 September 2020.[/caption]

Policy Thrust Peaks

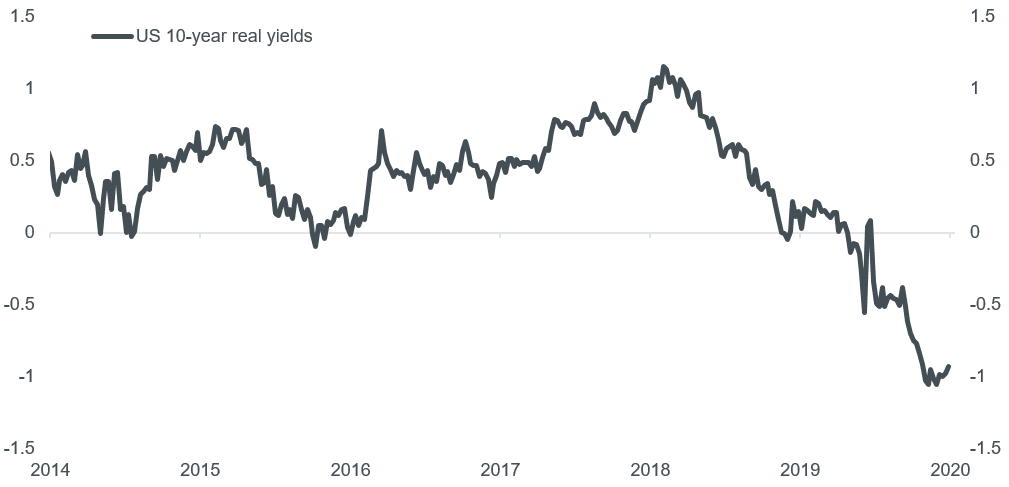

While both monetary and fiscal policy have played important roles in resuscitating and reviving the global economy from the coronavirus shock, the perception that these influences are now fading was a key factor dampening investor risk appetite in late Q3. On the monetary side, aggressive interest rate cuts, asset purchases and forward guidance from central banks have substantially eased financial conditions, as illustrated by the collapse of real interest rates and credit spreads since March (Exhibit 2). However, while further dovish central bank innovations are still possible in the months ahead, financial markets have priced in a lot already.

Exhibit 2: U.S. 10-year Real Yields (%)

[caption id=”attachment_323124″ align=”alignnone” width=”700″] Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 30 September 2020.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 30 September 2020.[/caption]

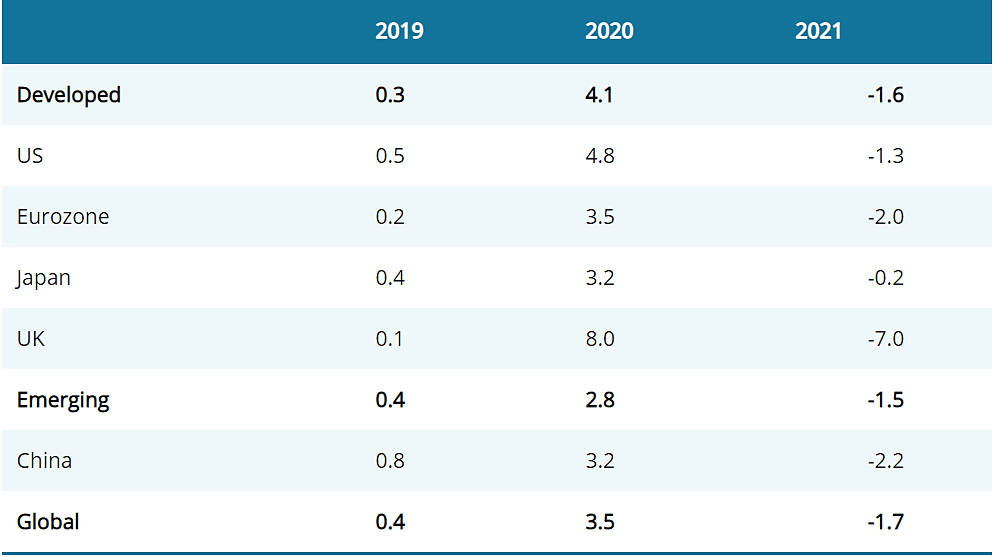

The bigger picture here is that, after decades of rate cuts and balance sheet expansion, the major central banks are now reaching the limits of their current toolkits. If growth or inflation disappoint in the future, fiscal policy will have to take more responsibility for stimulating the economy than it has done during the past decade. However, while fiscal authorities have responded decisively so far to the coronavirus shock in 2020, it is at the forefront of investors’ minds that many of these stimulus measures will expire this year. JPMorgan (JPM) economists estimate that while fiscal policy boosted global GDP (gross domestic product) by 3.6% in 2020, it could have a negative effect of 1.7% in 2021 as some emergency fiscal measures are withdrawn (Exhibit 3). Based on current policies, this 2021 fiscal cliff looks most dramatic in the UK.

Exhibit 3: Impact of Fiscal Policy as % of Real GDP

[caption id=”attachment_323135″ align=”alignnone” width=”600″] Source: Janus Henderson Investors, JP Morgan, as of 1 October 2020. Note: Figures after 2019 are JPMorgan forecasts.[/caption]

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, JP Morgan, as of 1 October 2020. Note: Figures after 2019 are JPMorgan forecasts.[/caption]

Complex and Fluid

Policy influences aside, the outlook for global growth remains highly sensitive to (and somewhat obscured by) the fast-moving spread of COVID-19 as we head into the final few months of the year. Optimists can point to the promising progress made on a number of fronts in the war against the coronavirus. Hospital and health care resources have been enhanced, COVID-19 treatment options have greatly improved, and testing and tracing capabilities have been expanded. Encouragingly, even though infection rates have risen significantly in many countries in recent months, hospitalization rates and death rates have not increased proportionately, even allowing for the usual lags.

However, a decisive victory against the pandemic still seems like a distant prospect, given the continued spread. The number of daily new COVID-19 cases is still close to its highs and the number of active global cases has doubled over the past three months. Another point worth noting is that many of the positive recent developments in the fight against the pandemic are developed-country phenomena – conditions remain more challenging in emerging economies in almost every respect. Also, the return of students to schools and further education establishments just as the weather cools in northern hemisphere countries is likely to sustain the uptrend in infection rates in many of these countries over the next couple of months, at least. The northern-hemisphere flu season usually peaks somewhere between December and February.

The most optimistic coronavirus scenarios generally focus on the prospects for the vaccine candidates now in development. However, even though the resources being deployed here are impressive, expectations should reflect the reality that most vaccines take eight to 10 years to get to market. There is also significant uncertainty about the potential effectiveness of any COVID-19 vaccines and the longevity of their protection. Beyond these considerations lies the logistical challenge of manufacturing and distributing enough doses to vaccinate a large proportion of the world’s eight billion people.

Still Social Distancing in 2021

As things stand, it seems fairly likely that some COVID-19 vaccines will be approved in a few major countries around the turn of the year. This approval stage can reasonably be seen as the start of an effective fightback against the coronavirus but it is unlikely to mark the end of the era of social distancing. A reasonable base case view is that most countries will maintain social distancing restrictions around current levels well into 2021. If the optimists are right, vaccine development could begin to have an impact on hospitalization and mortality rates in the second quarter of 2021, allowing some moderation of restrictions and hopefully some normalization of consumer behavior toward the middle of the year.

So, although we head into the fourth quarter of 2020 with the economic upswing expected to extend into 2021, investor confidence remains fragile, thanks largely to uncertainties surrounding the pandemic but also because of the general sense that monetary and fiscal policy support are on the wane. Investors must not only weigh up these complex and fluid macro, policy and health care issues, but also confront two other event risks overshadowing the final months of 2020: the U.S. election and Brexit.

The announcement that Donald Trump has tested positive for COVID-19 has added a new layer of uncertainty to an already unpredictable U.S. presidential election. While the polls and the betting markets continue to predict a Joe Biden victory, the congressional outcome will be nearly as important as the presidential race where financial markets are concerned. A Democratic clean sweep would undoubtedly be a game changer for U.S. politics, with significant implications for financial markets to digest. In simple terms, it would probably involve not only higher corporate taxes and greater regulatory intrusion across industries, but also a sizable, growth-boosting, redistributory fiscal stimulus.

Investors Want a Decisive U.S. Election Outcome

Given the prevailing uncertainties about the global outlook and the fact that the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) has relatively limited scope for economic stimulus, the ability of the next administration to implement its chosen fiscal program is likely to be a crucial driver of the market response to the election. While a Democratic clean sweep would be expected to lead to very different policies than a Republican one, both could be ultimately seen as being market friendly because of the policy control they give to the White House. Less-decisive electoral outcomes would probably undermine investor risk appetite if they are seen as extending the prevailing political gridlock. The prospect of a chaotic post-election outcome in which the result is delayed or contested is another risk that overhangs the November election.

Brexit: Narrow Deal or No Deal

The other notable political event that looms over Q4 is the Brexit negotiations. While little progress has been made toward a resolution in recent months – brinkmanship and bluffing have been typical features of every stage of the Brexit negotiations – we still expect a last-minute deal to emerge sometime around the EU Council meeting on October 15. However, even if such a deal does emerge, it is likely to be fairly narrow in scope, focusing largely on avoiding tariffs and quotas in manufacturing, with limited coverage of the service sector. That would amount to a fairly hard Brexit, which would be constructive for neither UK growth nor global investor appetite for UK risk assets. The next most likely outcome, a “no-deal” exit, could be even worse.

Into the Fog of Uncertainty

Investors can reasonably claim that they are entering the final few months of the year facing unusually low visibility on the global economic and political outlook. Somewhere in the Q4 fog of uncertainty lie various catalysts capable of shifting investor risk appetite quickly in either direction. While we see a gradual trend toward more normal social distancing as potentially a central theme for financial markets to focus on in 2021, investors will probably have to first endure some shocks, moments of doubt and bouts of market turbulence before they embrace this theme and its positive reflationary implications.

At times like this, we typically find it useful to understand investor positioning and sentiment, as this can often help identify areas of market vulnerability and opportunity and give insight into how financial markets might respond to shocks and surprises. While this task is more difficult than usual given the many unfamiliar features of the current economic and political backdrop, we have identified three key market themes at the beginning of Q4:

- Election Anticipation: Equity options prices show a pronounced hump in implied volatility curves around the U.S. election, indicating that investor uncertainty about this event is already elevated. While positioning does not look so extreme as to suggest that investors have fully priced in market-unfriendly election outcomes, it looks cautious enough to support the view that markets have the scope to rally on even a fairly neutral election result.

- Interest Rate Confidence: COVID-19 has crushed interest rate expectations. Yield curves are exceptionally flat in all the major economies and options prices show that the implied volatility of U.S. Treasuries is at an all-time low. Investors are confident that interest rates are going nowhere for a very long time. Investor faith in this theme has driven big inflows into liquidity-sensitive assets such as investment-grade bonds and gold, and has also supercharged long-duration, secular growth equities, such as technology stocks.

- Growth Skepticism: The direct and indirect consequences of the pandemic on the global economy have weighed heavily on cyclically sensitive assets this year. While policy interventions have cushioned the adverse impact of the coronavirus on the global economy, investors are still positioned for a long and slow path back to fully functioning economies. While decisive good news on COVID-19 could change perceptions quite quickly, a Democrat clean-sweep in the U.S. election could be another catalyst for a sharp rotation in market leadership, from 2020’s leaders to its laggards.

It certainly does not look as if this year will end quietly. Flare-ups in market volatility in the fourth quarter of 2020 seem inevitable as investors absorb news on the pandemic, the economy and politics. Investors should brace themselves for this turbulence by having some cash to put to work on market setbacks and by generally focusing on diversification and capital preservation. We expect to see plenty of investment opportunities as some uncertainties get resolved or market reactions create attractive entry points. Furthermore, with mainstream risk assets increasingly highly correlated and government bonds offering limited potential for hedging risk, we see this as a market environment in which alternative assets have an important role to play.

Knowledge. Shared

Blog

Back to all Blog Posts

Subscribe for relevant insights delivered straight to your inbox

I want to subscribe