Strategic Fixed Income: the predictable Japanification of US corporates

-

Jenna Barnard, CFA

Jenna Barnard, CFA

Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income | Portfolio Manager

Key Takeaways

- In early March I wrote that “as a result [of the COVID-19 crisis we] would not be surprised to see even lower yields on quality corporate bonds by the end of the year than where we started”, given the predictable policy response from central banks. Hence, “the coronavirus provides us an opportunity” as corporate bond investors to lock in attractive income for years to come.

- This bullishness on quality corporate bonds was unusual as the consensus was an opposite view: that corporate debt had turned into a multi-year bubble about to burst, and the volume of BBB rated debt (bonds issued just one notch above high yield) was extremely high in particular, raising fears of disorderly moves in bond valuations as a result of an external economic shock.

- While the Japanification of Europe has been in play for a few years and only recently became more of a consensus view, the US had remained an exception. Events have proven otherwise and our Japanification thesis is now a reality in the US, with US investment grade yields at 2% on average as compared to 2.9% at the beginning of 2020.

Key Takeaways

- In an article published in the UK in March, I wrote that “as a result [of the COVID-19 crisis we] would not be surprised to see even lower yields on quality corporate bonds by the end of the year than where we started”, given the predictable policy response from central banks. Hence, “the coronavirus provides us an opportunity” as corporate bond investors to lock in attractive income for years to come.

- This bullishness on quality corporate bonds was unusual as the consensus was an opposite view: that corporate debt had turned into a multi-year bubble about to burst, and the volume of BBB rated debt (bonds issued just one notch above high yield) was extremely high in particular, raising fears of disorderly moves in bond valuations as a result of an external economic shock.

- While the Japanification of Europe has been in play for a few years and only recently became more of a consensus view, the US had remained an exception. Events have proven otherwise and our Japanification thesis is now a reality in the US, with US investment grade yields at 2% on average as compared to 2.9% at the beginning of 2020.

In an article published early March in the UK (Coronavirus update from the Strategic Fixed Income Team) I wrote “When we do come out of the coronavirus ‘recession’ we will be in a world of ‘zero interest’ rates across the entire developed world; central banks buying even more investment grade corporate bonds via quantitative easing, a stumble towards fiscal stimulus and a cleansing of the ‘value’ areas of the credit markets that have been zombies for years (high yield energy being the most obvious example). As a result, I would not be surprised to see even lower yields on quality corporate bonds by the end of the year than where we started.” This view was rooted in the experience of the European and UK corporate bond markets in recent years and follows the experience of Japan decades ago.

‘Japanification’ is a loose term to explain the fact that many of the challenges that face the economies of the developed world today were first present in Japan twenty years ago. As weak growth, ever‑lower interest rates and negative bond yields have spread to the rest of the world, Japan has become the lens through which markets view these economies. Over the last year or so, the term ‘Japanification’ has appeared many times in the financial media. Much has been written on the ‘Japanification’ of Europe. We have referred to the Japanification trend repeatedly since 2012 when we began talking about Nomura economist Richard Koo’s theory of balance sheet recession in Japan.

Japanification spreads to the developed world

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks, regulators, and policymakers were forced to take extraordinary measures to prop up their economies. Despite their efforts, growth and inflation remained stubbornly low in the developed world, while the extended period of accommodative monetary policy resulted in ever decreasing interest rates and bond yields, at times into negative territory (Europe), with the US remaining an exception.

Falling government bond yields and interest rates, some into negative territory, over the last few years, were to us clear indications of the Japanification of Europe. We have long spoken of the failure of mainstream economics, which has repeatedly over‑forecast growth and inflation in the developed world and looked to focus on long‑term thematic factors instead, which weigh down bond yields such as demographics, excess debt and the impact of technology.

As a result, between 2014-18, most countries in the developed world only cut interest rates. North America was an exception with the Bank of Canada and US Federal Reserve (Fed) pushing on with modest interest rate hiking cycles. This interest rate divergence had already come to an end with modest rate cuts from the Fed in 2019 and was accelerated in 2020 as a result of the pandemic. The significant emergency measures taken by major central banks to combat the crisis, and the Fed in particular, slashed government bond yields in the US and elsewhere. As government bond yields declined further, investors looked to the corporate bond markets, specifically in the US.

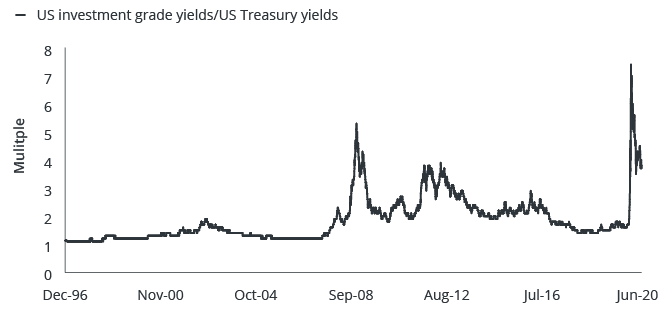

The Japanification of volatility

Similar to the experience in Japan, in the COVID‑19 crisis central banks succeeded in suppressing volatility through various extraordinary stimulus measures including lowering rates, quantitative easing, yield targeting, and forward guidance. Thus, as a result, policymakers dampened interest rate volatility and reduced systemic risk, creating an idyllic environment for investing in corporate bonds.

In the US, the Fed’s programmes of support for investment grade and, to a lesser extent, some high yield default risk (through purchases of high yield exchange traded funds) further dampened volatility in the bond markets. The end result was predictable enough: for investors in need of income, the exceptionally low and stable government bond yields made investment grade bonds an attractive alternative.

[caption id=”attachment_322396″ align=”alignnone” width=”660″]

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, ICE Bank of America indices, Bloomberg, daily data, as at 31 August 2020.[/caption]

The era of ‘new sovereigns’

According to a research paper by Bank of America, around two‑thirds of the global fixed income markets currently yield less than 1%. European sovereign bond yields fell dramatically in the years post the GFC, and in 2010-11, when the yield on 5‑year bunds fell below 1%, bond investors rotated out of government bonds into the credit markets.

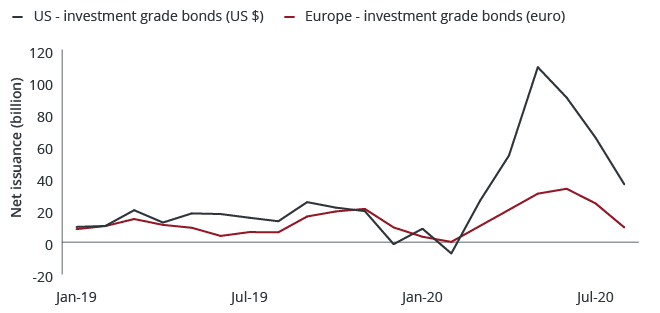

Similar to the experience in Europe, the US corporate bond market has seen increased demand and large inflows of capital in recent months. Catalysed by the actions of the Fed, the primary market (issuance market) for US corporate bonds reopened quickly in the crisis – the floodgates opened for investment grade issues in March and the high yield market reopened with a bang the following month. Borrowers took advantage of the lower borrowing costs to procure sufficient funds for their operations in the difficult months ahead and/or extend the maturity of their debt by selling longer- and longer‑dated bonds to yield hungry investors.

With low levels of inventories for trading in the secondary market, demand for new issues has been huge in the primary bond market with many deals oversubscribed, despite a record‑breaking pace of supply ($1.4 billion in investment grade issuance through to 8 September, compared to $0.8 billion for the whole of 2019).

[caption id=”attachment_322717″ align=”alignnone” width=”660″]

Source: BNP Paribas, Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, monthly data, as at 31 August 2020. Net issuance volumes less fallen angels and buybacks. A fallen angel is a bond that has been downgraded from an investment-grade rating to sub-investment-grade status, due to a deterioration in the financial condition of the issuer. A bond buyback occurs when a company approaches the open market and repurchases its bonds from holders.[/caption]

Flows into the investment grade and high yield markets have continued well into August. They have been further boosted by a resurgence in overseas buyers, given that the cost of hedging back to local currencies have come down with the decline in interest rates.

Interestingly, given the paltry returns on government bonds, investment grade corporate bonds have now become the alternative source for potentially ‘safe’ yield,, as the search for yield has left little choice but to buy bonds from quality companies. Thus, well‑known, quality, ‘sensible income’ generating companies are almost the new sovereigns, and their bonds, almost the new benchmark reference rates.

For the rest of 2020, we expect to see lower net corporate bond issuance, as companies, having raised sufficient funds in the first half of the year, will likely be more aggressive in managing their credit ratings and borrowing levels through bond buybacks and repayments.

Lower volatility is a boon for corporate bond markets

Lower volatility helps to improve the risk/return profile for fixed income assets despite lower yields. In Japan, corporate bonds have, perversely, delivered solid risk‑adjusted returns over the years, despite offering lower yields and credit spreads, compared to their equivalents in Europe and the US. A historical analysis by Bank of America has shown that over the past two decades, Japanese investment grade corporate bonds, with an average credit spread of around a quarter to one‑fifth of their equivalents in Europe and the US, have delivered a much higher risk‑adjusted return, helped by the tailwind of lower volatility.

So long as central banks can maintain a credible commitment to low interest rates for years to come, based on their new economic models of ‘economic scarring’ from the COVID-19 crisis and too low inflation, this idyllic environment can continue as it has done in other countries. However, US 10‑year sovereign bond yields now look about 50 basis points too low relative to our models of the rate of change of economic data1. The ‘easy money’ has been made in investment grade corporate bonds as the predictable Japanification theme has played out in months, rather than years.

1As at 18 September 2020.