Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Benjamin Graham, widely known as the ‘father of value investing’, famously tells us: “Diversification is an established tenet of conservative investment.[1] The pivotal word in that well-known quotation is ‘conservative’ and, accordingly, it establishes the fact that the ultimate aim of diversification is to reduce risk, i.e. the chance that an investment’s actual returns will diverge from an anticipated outcome, potentially reducing the number and the severity of stomach-churning ups and downs.

Portfolio diversification is a foundational concept in the world of investing and there is a consensus amongst most investment professionals that, whilst it isn’t a guarantee of profit or an insurance against loss – the carnage of 2008 and 2009 will have taught most investors that – it is nevertheless a key element when seeking to achieve financial goals over the long term whilst minimising risk.

So … what are those risks, how well does diversification deliver against that objective, and how does one build diversification into the construction of an investment portfolio?

Investors find themselves forced to contemplate two fundamental, but very different, forms of risk when establishing a portfolio: ‘systematic’ and ‘unsystematic’. The former – also commonly referred to as ‘market’ risk – can often be undiversifiable in that it typically pervades the entire investment landscape: examples would include the post-2008 global financial crisis and indeed the worldwide pandemic we are experiencing currently. Given that these phenomena are unlikely to be associated with a specific geography, industry, sector or company, the associated risks can rarely be mitigated, let alone eliminated – they must simply be accepted.

Unsystematic risk is diversifiable however in that it is specific – either to a region, a country, an industry, a sector or an individual company. When seeking to dilute this form of risk through diversification, the approach is to invest in a variety of assets such that they will not all be influenced by market events in the same way. Diversification is essentially, therefore, a risk management strategy that combines a wide variety of investments within a portfolio, on the expectation that the positive performance of certain holdings will neutralise the negative performance of others.

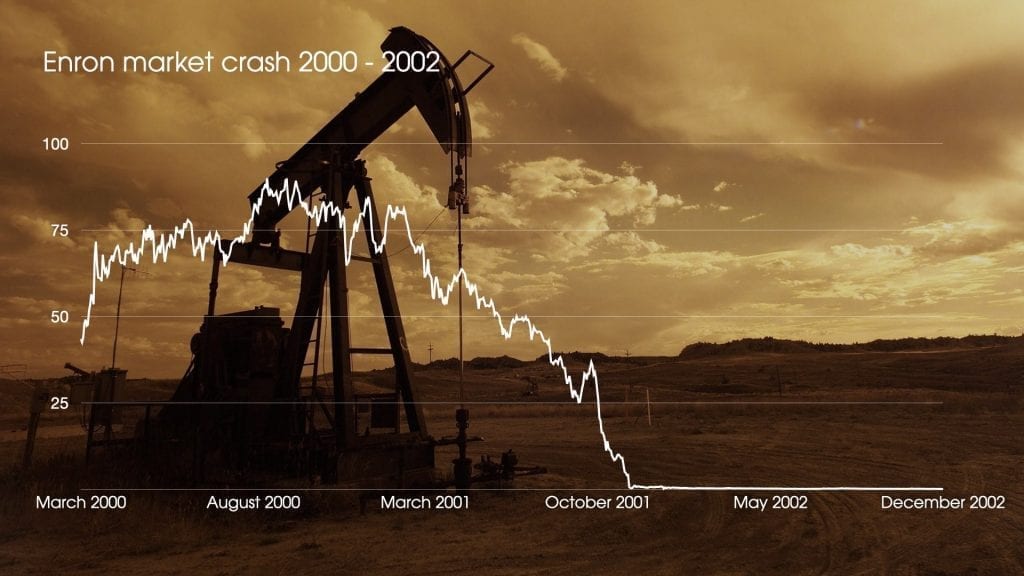

In short, it’s the practical application of the old adage: ‘Don’t put all your eggs in one basket’. Let’s examine the principle in practice, first by looking at some relatively extreme examples. Consider the employees of Enron, the US energy company, among whom it was commonplace to invest in the shares of their employer. As the true extent of the false accounting scandal unfolded, the company’s share price, which had achieved a high of just under US$91 in mid-2000, plummeted to less than US$1 by the end of November 2001. The vast majority of employees lost not only their jobs but also their retirement funds and, in many cases, their life savings. Investors in Amazon shares at the turn of millennium will have experienced a similarly rocky ride, albeit with a rather happier outcome ultimately. In December 2000, Amazon shares were trading at over $100 but, by the following October, they had fallen to below $6 … and one would have had to wait until December 2007 to see them climb back above $90.

A diversified portfolio won’t guarantee to eliminate losses but will deliver its returns with lower volatility. It’s why some say that diversification is the only free ride in investing … but remember that the benefits hold only if the portfolio’s assets are not correlated, i.e. that they will respond differently, and often in opposing ways, to market influences and events. When share prices fall, for example, bond prices often rise, as a function of investors switching their assets into what is considered a lower-risk investment.

Investing in a single stock would seem to tread that very fine line between bravery and folly – intense concentration of that kind leaves no margin for error – but investing in a single sector runs the risk of proving similarly unwise. Consider the pummelling that the global airline industry is now experiencing, courtesy of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shares in ICAG, the parent group of British Airways, were trading at above £6.70 as recently as mid-January 2020, but are now languishing at circa £1.93; in terms of budget airlines, the Ryanair share price fell over 40% from its 2020 high before starting to bounce back in May.

It is generally prudent, therefore, to diversify by both stock and sector. Investors who loaded up on technology stocks in 2000 lost their shirts when the dot-com bubble burst and the sector rapidly fell out of favour; financial stocks similarly went into freefall in late 2007 and early 2008 as a result of the US sub-prime mortgage crisis.[2] Diversifying by asset class offers a further dimension – indeed asset allocation can be regarded as the exercise most central to a diversification strategy.

The range of asset classes would conventionally include:

Finally, investors can reap further benefits from diversification by considering location, location, location – that is to say, seeking investment opportunities beyond one’s own geographical borders. Factors which might be depressing the US economy may not be impacting the Japanese economy in the same way, whilst volatility in US equity markets may have little bearing on the European bond market.

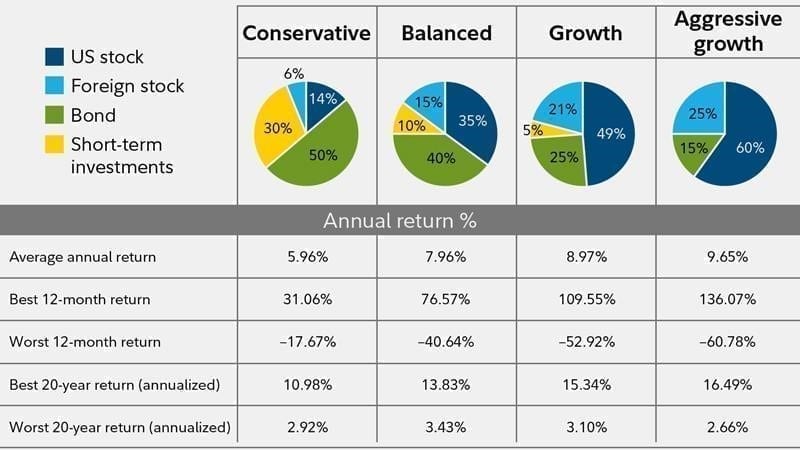

So much for the theory – does diversification work in practice, i.e. what is its impact on long-term investment performance and portfolio volatility? The charts below throw a good deal of light on the matter. They show the average annual return, and the best and worst annual and 20-year returns, across a range of four hypothetical US portfolios which differ in their asset allocation – the more conservative the portfolio, the more diversified its holdings … and vice versa. The returns shown are total, in that they include reinvested dividends, over the period 1926 to 2015.[3]

As you can see, the most aggressive portfolio had an average annual return of 9.65%. Whilst its best 12 months generated a return of 136%, its worst 12-month return would have seen the value fall by over 60%. That sort of volatility is likely to be too severe for most investors to tolerate, probably too much volatility for most investors to endure. Modifying the allocation of assets slightly would have very little detrimental impact on the average annual return – still around 9% – but would narrow the range of extremes on the high and low end.

The overall results demonstrate that injecting more fixed-income assets to portfolio will reduce one’s expectations for long-term returns somewhat, but is likely significantly to reduce the portfolio’s volatility – it’s a trade-off many investors feel is one worth making, particularly if they are approaching retirement age and, as a consequence, are more risk-averse.

Source: Fidelity, What is portfolio diversification, accessed 02/09/2020

How many is too many?

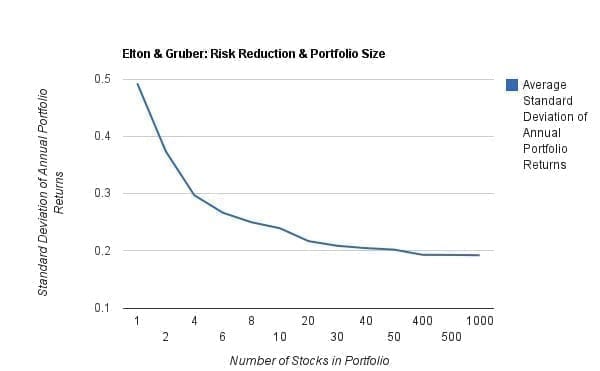

Having subscribed to the view that diversification is a sound investment strategy, an obvious question is “How many?”, i.e. how many individual stocks are required to reduce a portfolio’s volatility whilst maintaining the potential for attractive returns. Again, research reveals the answer. In the late 1970s, two academics – Edwin Elton and Martin Gruber, conducted a comprehensive analysis of the benefits of diversification and demonstrated that most of the benefit of further diversification recedes once a portfolio contains at least 20 to 30 securities – see the chart below.

Source: Edwin J Elton and Martin J Gruber, Risk Reduction And Portfolio Size: An Analytical Solution, The Journal Of Business, Volume 50, Issue 4, October 1977.

This is not to say that there is no merit in portfolios which comprise more than 30 stocks, merely that the benefits don’t lie in the area of reduced volatility. However, a lack of time, resources and stock-picking ability make it difficult for individuals to build and manage a well-diversified portfolio, and it is this challenge which explains why pooled vehicles like investment trusts are so popular with retail investors.

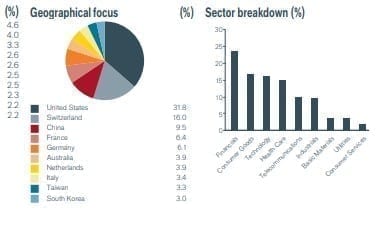

A good example of diversification in practice is the Henderson International Income Trust, managed for the last nine years by Janus Henderson’s Ben Lofthouse. The Trust aims to deliver a high and rising level of dividends, coupled with capital appreciation over the long-term, from a focused and internationally diversified portfolio of securities outside the UK. It has a flexible mandate in terms of both geographical focus and market capitalisation, but seeks out solid companies available at attractive valuations and with good cashflows, that are therefore in a position to deliver a dividend yield in excess of 2% (the current yield is circa 4% pa), and to grow their dividend payouts over the longer term. It doesn’t invest in UK stocks or stocks with a dual listing which includes the UK – indeed, it is designed as a diversifier for UK investors, and particularly those holding UK equity income stocks.

Janus Henderson’s managers have a great deal of equity income expertise across international markets, and they leverage that broad and deep regional understanding in order to build a diversified international portfolio. Ben determines the overall asset allocations, but is assisted by other Janus Henderson managers with specific expertise in different geographical regions and so, in many ways, the Trust can be regarded as a ‘Global Income – Best Ideas’ portfolio. The current asset allocation – by region and sector – can be seen below.

Source: Henderson International Income Trust Fact Sheet 31st July 2020

In the context of the current climate, the portfolio has been positioned fairly defensively over recent months and, whilst the trust contains higher-yielding stocks, a key focus has been balance sheet strength – over 90% of the corporate bond holdings are classified as ‘investment grade’ for example – and so Ben is confident that the businesses held have the potential to weather the storm reasonably well. In terms of the specific threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, the managers have looked closely at those holdings which were likely to be specifically affected – by, say, a reduction in passenger numbers – and removed those from the portfolio. Needless to say, diversification by region and by sector will continue to play a major part in the trust’s investment strategy, both in terms of shielding shareholders from threats and seizing potentially lucrative opportunities as they arise.

Glossary

Asset allocation

The allocation of a portfolio according to an asset class, sector, geographical region, or type of security.

Bond

A debt security issued by a company or a government, used as a way of raising money. The investor buying the bond is effectively lending money to the issuer of the bond. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of fixed periodic payments, and the eventual return at maturity of the original money invested – the par value. Because of their fixed periodic interest payments, they are also often called fixed income instruments.

Capital appreciation

Capital appreciation is an increase in the price or value of assets. It may refer to appreciation of company stocks or bonds held by an investor, an increase in land valuation, or other upward revaluation of fixed assets.

Commodity

A physical good such as oil, gold or wheat. The sale and purchase of commodities in financial markets is usually carried out through futures contracts.

Diversification

A way of spreading risk by mixing different types of assets/asset classes in a portfolio. It is based on the assumption that the prices of the different assets will behave differently in a given scenario. Assets with low correlation should provide the most diversification.

Dividend

A payment made by a company to its shareholders. The amount is variable and is paid as a portion of the company’s profits.

Fixed-income assets

Fixed income refers to any type of investment under which the borrower or issuer is obliged to make payments of a fixed amount on a fixed schedule. For example, the borrower may have to pay interest at a fixed rate once a year and to repay the principal amount on maturity.

Portfolio

A grouping of financial assets such as equities, bonds and cash. Also often called a ‘fund’.

Systemic risk

The risk of a critical or harmful change in the financial system as a whole, which would affect all markets and asset classes.

Un-systemic risk

Unsystematic risk is the risk that is inherent in a specific company or industry. By investing in a range of companies and industries, unsystematic risk can be drastically reduced through diversification.

Yield

The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For equities, a common measure is the dividend yield, which divides recent dividend payments for each share by the share price. For a bond, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Volatility

The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. It is used as a measure of the riskiness of an investment

[1] Source: Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor, 1985

[2] Source: Journal of Corporate Finance – Volume 48, 2018

[3] Source: Fidelity Investments. Asset mix performance figures are based on the weighted average of annual return figures for certain benchmarks for each asset class represented. Historical returns and volatility of the stock, bond and short-term asset classes are based on the historical performance data of various indexes from 1926 through the most recent year-end data available from Morningstar. Domestic stocks are represented by the S&P 500 1926 – 1986, the Dow Jones U.S. Total Market 1987 – most recent year end; foreign stocks are represented by the S&P 500 1926 – 1969, MSCI EAFE 1970 – 2000, MSCI ACWI Ex USA 2001 – most recent year end; bonds are represented by US intermediate-term bonds 1926 – 1975, Barclays US Aggregate Bond 1976 – most recent year end; short term represented by 30-day US Treasury bills 1926 – most recent year end.