Knowledge. Shared Blog

June 2020

The Shape of Credit

-

Jason England

Jason England

Portfolio Manager -

Daniel Siluk

Daniel Siluk

Portfolio Manager -

Nick Maroutsos

Nick Maroutsos

Co-Head of Global Bonds | Portfolio Manager

In this Q&A, Portfolio Managers Jason England, Nick Maroutsos and Dan Siluk discuss the factors shaping credit markets, from central bank support to potential resilience from financials.

Key Takeaways

- Corporate earnings and cash flows are under strain, but while defaults are likely to increase, they should continue to be largely contained to sub-investment-grade issuers.

- Massive and proactive central bank support measures have injected confidence into markets, but this does not preclude sporadic bouts of future volatility and warrants a selective approach.

- We believe more resilient opportunities are likely to be found in higher-quality, shorter-dated investment-grade issues and continue to favor financial sector bonds and corporates with defensive attributes.

What’s driving credit markets?

Driven by continued uncertainty around the COVID‑19 pandemic, global financial markets have been highly volatile and, while recently calmer, they remain in a state of flux. Prospects for a vaccine coming to market sooner than expected and lockdowns ending versus increasing contagion rates, rising deaths and risks of a second wave of infection seem to be the main drivers of market direction.

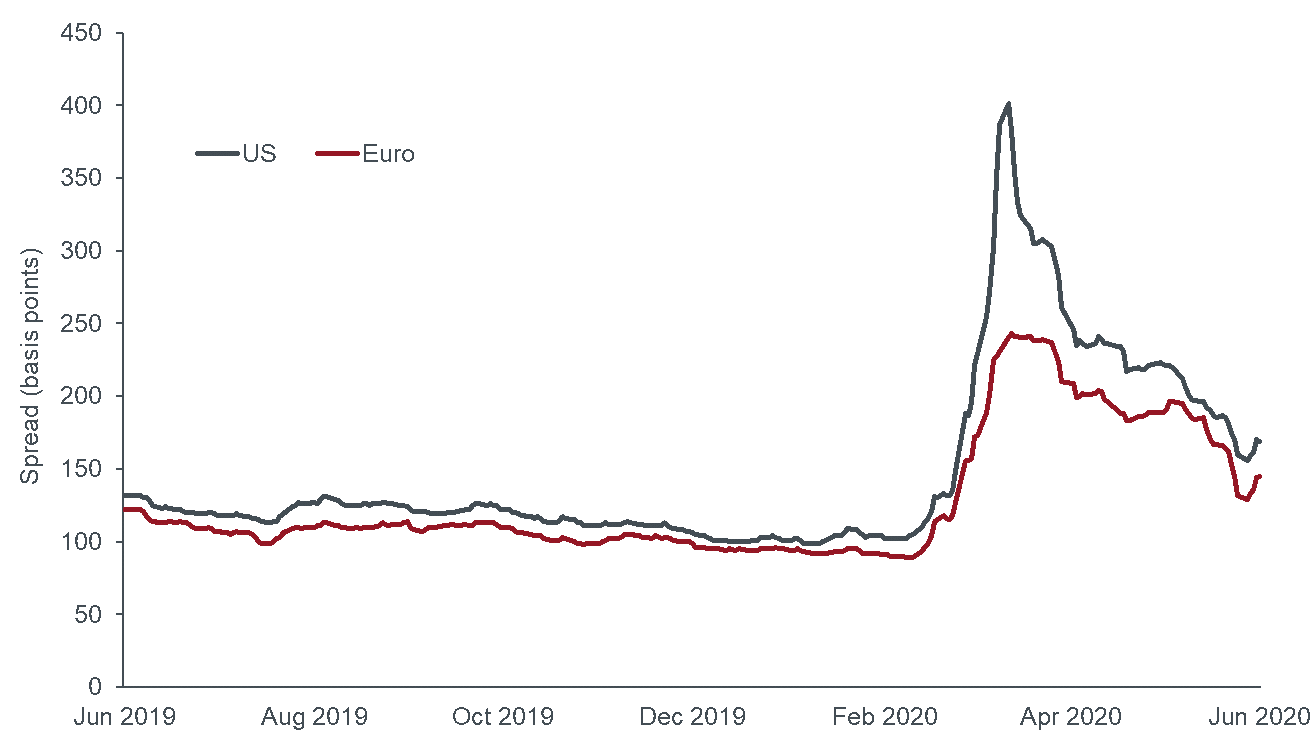

Although credit markets have received support from central banks that have introduced new programs to either buy corporate bonds directly or allow some corporate bonds to be repo‑eligible collateral,1 there has nevertheless been considerable stress. As a result, investment-grade credit spreads are generally wider today than they were at the end of February, when the crisis began (see chart below).

Credit Spreads on Investment-Grade Corporate Bonds

[caption id=”attachment_301561″ align=”alignnone” width=”1316″] Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index, government option-adjusted spreads, 12 June 2019 to 12 June 2020. Option-adjusted spread measures the spread between a fixed income security rate and the risk-free rate of return, which is adjusted to take into account an embedded option. The ICE BofA US Corporate Index represents U.S. dollar-denominated investment-grade corporate debt publicly issued in the U.S. market. The ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index represents euro-denominated investment-grade corporate debt publicly issued in the European market.[/caption]

Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index, government option-adjusted spreads, 12 June 2019 to 12 June 2020. Option-adjusted spread measures the spread between a fixed income security rate and the risk-free rate of return, which is adjusted to take into account an embedded option. The ICE BofA US Corporate Index represents U.S. dollar-denominated investment-grade corporate debt publicly issued in the U.S. market. The ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index represents euro-denominated investment-grade corporate debt publicly issued in the European market.[/caption]

In order to assess whether this repricing presents an opportunity or a risk, it is critical to understand if these changes are mainly driven by technical or fundamental factors. Unsurprisingly, technicals have so far been the driving factor for credit spreads widening. Initially, investor demand for cash led to indiscriminate selling of risk assets, including credit. More recently, markets have given way to optimism, fueled by political will and central bank support initiatives. But while underlying corporate fundamentals have taken a back seat, historical experience suggests that in the medium to long term, fundamentals will regain their position as the most important variable driving credit spreads.

Have credit fundamentals changed over the last few months?

Most sectors and businesses are suffering from a reduction in revenue and profitability. But of more importance for credit fundamentals is the accompanying impact on free cash flow. Companies will try to reduce cash burn as much as possible by reducing, or extending out, capital expenditure and reining in variable costs.

As positive cash flow becomes harder to generate and leverage increases, it is important to focus on a company’s liquidity position — a key indicator as to whether it will be able to survive the downturn. How much cash does it have on hand? Does it have access to credit lines or a revolving credit facility? Are corporate bond markets open for new deals?

In answering these questions, it is important to make sure that these credit facilities are committed; if they are not, then it is all too easy for a bank to renege on these “commitments” in times of stress. Companies in stress will often draw down on these lines and choose to hold the cash on the balance sheet. That way, management can guarantee access to liquidity and buy itself time for demand to recover.

Credit market issuers have become somewhat polarized. Higher-quality investment-grade companies have a better chance of weathering the storm given their access to cash, bank credit lines and capital markets (equity and/or credit). For the latter, the U.S. primary debt market has seen a record amount of issuance over the last few months, dominated by strong investment-grade companies. Smaller, more indebted and lower-rated companies will likely struggle, as they have fewer levers to pull.

Given this last credit cycle was one of the longest on record with almost unlimited access to liquidity, some companies will now struggle to refinance and stay solvent. So not only is there likely to be more credit rating downgrades but also an increase in defaults. However, defaults, consistent with history, could remain concentrated in already lower-rated high-yield companies.

What are the rating agencies saying about downgrades?

Moody’s recently published a report that analyzed movements in ratings since 1920, a period that includes other economic shocks such as the Great Depression of 1929. The report emphasizes that while softer-than-expected revenue and free cash flow will impact credit quality, rating agencies do attempt to rate through the credit cycle and capture lasting changes in credit quality. For those companies that had a historical rating change (either an upgrade or downgrade), Moody’s examined more than 100 years of data on U.S. companies and noted it only reversed a rating change about 3% of the time within one year and only 20% after five years.2 The report also states:

Net downgrades rise in credit downturns, but only by a small amount. This is unsurprising as deteriorating financial and economic conditions are a key indication that aggregate default risks are rising. However, the degree of downgrades is relatively limited, particularly for higher-rated issuers that should be more robust in the face of normal cyclical developments. During the past three credit downturns, on average, ratings have only declined by around half a notch.

Nevertheless, we do expect that the COVID-19 crisis may result in a higher-than-average number of BBB bonds (the lowest tier of investment grade) transitioning to high yield given the size of the BBB market. In fact, in recent months, BBB has made up around 50% of the U.S. investment-grade market, up from around 35% prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).3 In our experience, bonds that go from investment grade to high yield can fall around 10% in price, so single-name issuer selection remains crucial.

What are the rating agencies saying about defaults?

Before talking about defaults, it is worth stressing that most data examine just the high-yield universe, as there are too few investment-grade defaults to allow meaningful analysis. For example, S&P’s

average global one-year default rate for the lowest investment-grade-rated corporate bond over the last 38 years is just 0.2%, with a high of 1.4% in 1983. The long-term annual global high-yield default rate is 3.7%.4

The current COVID-19 crisis is expected to drive a rise in high-yield default rates. Specifically, S&P is forecasting that the trailing 12-month default rate for U.S. high yield will jump to 10% by the end of December 2020, up from 3.1% in December 2019. This assumes a global recession this year and is partly driven by volume: The percentage of select high-yield issuers (those with a B or lower rating) stood at an all-time high of just over 30% in March 2020.5

As with previous crises, we expect heightened default risk to remain more or less fully contained within the sub-investment-grade universe and, specifically, sectors such as energy, leisure, gaming and retail.

Is the current crisis the same as the GFC?

This COVID-19-driven economic downturn is different from the GFC, as the financial sector is not the source. The severity of the crisis will depend on the individual sector, varying from those heavily impacted (travel, leisure, energy, luxury products) to those less so (food, consumer staples, infrastructure, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, technology).

Unlike during the GFC, when pure corporate credits were generally preferred over financial credit, the current crisis sees the reverse as true. Since the GFC, through various new regulations, banks have been forced to substantially increase their loss-absorbing capital bases and should be better set to survive. Banks will obviously be impacted by credit losses in their corporate, property and personal loan books, but well-managed banks are expected to have sufficient capital to take those hits.

One fortunate advantage of having stronger banks this time around is that they are more willing to extend credit to sound corporates, even those in more volatile sectors.

What are the technical factors that are driving the market?

Central banks have been proactive in attempting to support global economies and financial markets, with several initiatives supportive of credit markets. These include the European Central Bank’s €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which will be conducted through the end of 2020 and includes all the asset categories eligible under the existing asset purchase program, and the decision by the Federal Reserve (Fed) to buy corporate bonds, including select high-yield bonds. In April, the Fed detailed various measures that give it the firepower to inject up to $2.3 trillion of support into credit markets and the wider economy.6 Elsewhere, the Bank of England has extended its corporate bond purchase scheme, and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has allowed some corporate bonds to be repo eligible. The RBA is also helping to administer the Australian government’s Structured Finance Support Fund, which is aiding issuers and the securitized market by buying primary and secondary asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities.

Given this extraordinary support from central banks and show of additional firepower if needed, technical factors are currently overwhelming pure credit fundamentals. Credit investors have gained comfort that there is a potential “buyer of last resort” and credit spreads have since narrowed from their peak crisis wides.

What are the main takeaways and where do we see opportunities?

The global financial outlook is still uncertain. As such, we remain attentive to the possibility of volatility and with it, credit spread widening. The pace of credit rating downgrades will likely increase and defaults rise, but this should continue to be largely contained to sub-investment-grade issuers.

That being said, the coordinated efforts by global central banks to inject confidence and stability back into the system by supporting credit should not be undervalued. Almost universally, central banks telegraph that they will continue to do whatever it takes. The wider spread on corporate bonds also may offer investors the opportunity to benefit from potentially higher returns. As such, at this juncture, we believe investors should consider adding some credit risk while remaining alert to ongoing uncertainty and sporadic bouts of future volatility.

We firmly believe that more resilient opportunities in credit are most likely to be found in higher-quality, shorter-dated investment-grade issues and continue to favor financial sector bonds and corporate sectors with defensive attributes. We also see opportunities in more liquid jurisdictions such as the U.S., which continues to have a high degree of central bank support.

Global Fixed Income Perspective

Quarterly insight from our fixed income teams to help clients navigate therisks and opportunities ahead..

Read Now

1A security that is eligible for repurchase.

2“Ratings move with the credit cycle but do not amplify it,” Moody’s, Sector In-Depth. 12 May 2020.

3Bloomberg. ICE BofA BBB US Corporate Index as a % of ICE BofA US Corporate Index, 31 May 2020.

4“S&P 2018 Annual Global Corporate Default and Rating Transition Study,” 9 April 2019. Covering 1981-2018 inclusive.

5“Default Transition and Recovery,” S&P Global Ratings. 20 March 2020.

6“Federal Reserve takes additional actions to provide up to $2.3 trillion in loans to support the economy,” Federal Reserve press release. 9 April 2020; “COVID-19: Policy responses by G20 economies,” Deutsche Bank. 21 May 2020.

Knowledge. Shared

Blog

Back to all Blog Posts

Subscribe for relevant insights delivered straight to your inbox

I want to subscribe