Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Elissa Johnson, Portfolio Manager and secured loans specialist within the Secured Credit Team, discusses the probability of corporate defaults in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis and whether the risks are priced in.

European secured loan markets fell sharply in March as the extent of the Covid‑19 crisis became apparent, before rallying strongly in April, as the substantial monetary and corporate focused fiscal stimulus led investors to rethink the economic impact of the crisis.

The key questions for investors are: how much risk is now in the price and is now a good time to invest?

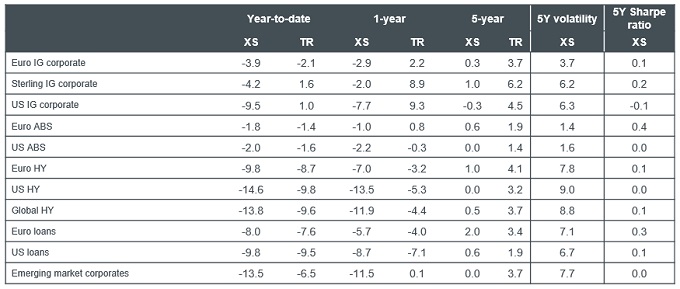

Table 1 shows the returns, year‑to‑date through mid‑May, for credit markets on both sides of the Atlantic. Unsurprisingly, credit has underperformed government bonds since the crisis began. However, investors are wondering if there are opportunities to be had in European loans and other credit asset classes, as they now offer higher yields than in the recent past; for example, the 5‑year discount margin for European loans was 5.9% on 14 May 2020.

Table 1: returns across credit markets — Covid‑19 impact has been severe

Source: Credit Suisse US and European leveraged loan indices; ICE BofA US and European investment grade and high yield indices and emerging market liquid corporate index, Barclays (ABS), as at 30 April 2020.

Note: Fixed rate assets excess return versus swaps; Floating rate assets total return less Libor. TR = total returns, XS = excess returns, IG = investment grade, HY = high yield, ABS = asset-backed securities.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

There is a broad consensus that the world economy will experience a very deep recession in the second quarter of 2020 but the scale and speed of the rebound remains a debate. The first quarter delivered a global gross domestic product (GDP) growth of ‑1.6%, with a steeper drop in Europe of ‑2.7% owing to the imposition of lockdowns in March, which restricted economic activity.

We note that current consensus forecasts for global GDP growth this year are at ‑8.6%1 in Q2, ‑5.6%1 in Q3 and ‑3.0%2 for the full year. European growth is forecast to be even lower, with the consensus forecast at ‑6.4%2, due to the substantial lockdowns seen in Europe and the continuing restrictions on economic activity as we move through Q2.

This suggests that corporate revenue and earnings will be much lower than otherwise expected; however, in our view, the substantial stimulus provided by the authorities means many companies have avoided immediate issues, as their cost base and liquidity outlook have been supported significantly.

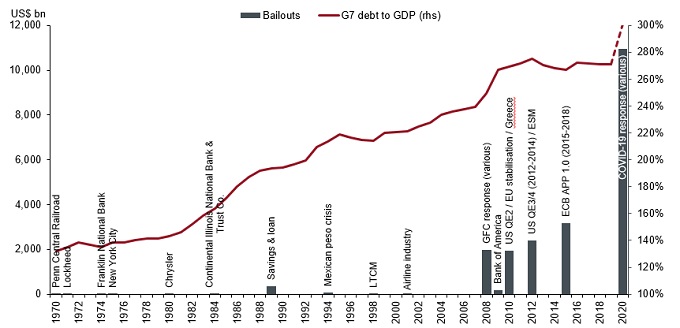

Chart 1 shows the level of stimulus which has been provided over time; the latest stimulus dwarfs those even in the recent past. The data captures measures announced up to 27 April 2020 and hence the continuing increase in stimulus seen since then (for example, UK’s extension of its furlough scheme through to October) is not included.

Chart 1: historical bailouts versus G7 debt to GDP

Source: Deutsche Bank, Default Study, 2020: Default seems to be the hardest word, 27 April 2020

Note: bailouts (2020 USD prices) versus G7 public and private debt to GDP

Most importantly in this crisis, fiscal stimulus has been directly provided to corporates in a number of European countries. Governments, including those of the UK, France and Spain have provided significant support for labour costs, which for most businesses comprise a majority of their fixed costs (labour costs including wages, social security contributions, rent, tax, interest and maintenance capex). Some governments have also provided significant liquidity support directly to corporations, either via tax deferral schemes or government‑backed loans. In the UK, there are various small business grants available too. In some jurisdictions, such as Italy and Poland, rent is not payable by businesses if they are unable to open.

All this fiscal support has enabled companies to offset their fixed costs while earning significantly reduced revenue. This immediate and significant level of government support has meaningfully reduced the liquidity threat to many businesses and hence considerably reduced — albeit not eliminated — the spike in defaults that we believe we may otherwise have seen given the lockdowns in many European economies.

This credit cycle is unique in the European loan market. It is the first cycle where the majority of loans have not benefited from maintenance covenants. The impact of maintenance covenants in an environment where EBITDA falls sharply is that events of default under the loan documentation are potentially triggered.

Historically the impact of a covenant breach would be to gather lenders, the borrower and the owner, typically a private equity firm, around the negotiating table, and in many cases lenders would grant a temporary covenant waiver in return for additional return (eg, a higher margin on their loan) and potentially also a reduction in risk through an additional equity injection.

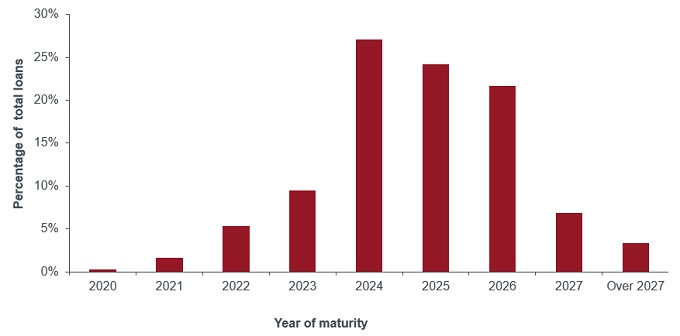

This time around however, with no imminent maturity wall in the European loan market (see chart 2), default is most likely to occur via either:

Chart 2: European loans — maturity profile

Source: Credit Suisse, as at 30 April 20

Liquidity risk has been reduced in economies where there are substantial restrictions on normal working practices by the support of government schemes. We have also seen instances where owners have provided additional liquidity support, although that has generally been pari passu with existing lenders or super senior debt — such as that reported for leisure business, Hotelbeds3.

We would note that given the looser documentation terms that we have seen over the past two years in leveraged credit markets generally, the ability of borrowers to incur additional debt in both the high yield and leveraged loan markets is significantly higher than it would have been under documentation standards in the last downturn.

Adjustments to EBITDA, including management add‑backs (we are expecting to see Covid‑19 related costs and potentially even the impact of the lower absorption of overheads as adjustments), and certain carve outs to exclude certain negative items, could allow the EBITDA used for calculating debt incurred to be a lot higher than it might at first appear given the company’s operating profits.

In addition, many loan agreements permit baskets of debt to be raised without adding to net debt. Hence, we think some borrowers have significant flexibility to incur debt under their existing loan documentation without needing lender approval, all of which should enhance liquidity.

Permitted debt will generally also include the company’s existing revolving credit facility (RCF) facility. We have seen many companies, indeed, perhaps even the majority, draw or fully draw on their RCF facilities to enhance their liquidity position. While these facilities do typically contain springing leverage covenants — ie, leverage tests when a certain percentage of the RCF (usually 35‑40%) is drawn at the quarter end — our engagement with private equity owners suggests that banks are likely to waive these covenants if needed, or that they have sufficient liquidity to partially repay the RCF for the quarterly testing date.

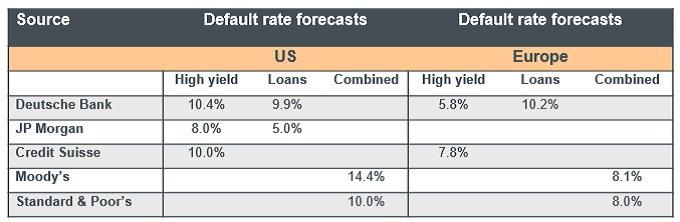

Table 2 displays some of the current forecasts for default in the loans and high yield markets.

Table 2: selected default forecasts

Source: Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, Deutsche Bank, Moody’s and Standards & Poor’s. For dates please see note 4.

In our view, the spike in default rates may prove not to be as high as many expect in the next ten months (or 12 months since Covid‑19 hit Europe). The fiscal support programmes; availability of (government‑backed and other) loans and support from owners (eg, Hotelbeds), combined with flexibility in the documentation, will, we think, enable many companies to survive through the lockdown period and the initial slow economic growth that is likely to follow.

However, with many companies taking on additional debt in the form of emergency loans such as travel company, Tui’s €1.8bn loan from KfW5, transportation and shipping company, CMA CGM’s €1.05bn state‑backed loan5 and theme park operator, Parques Reunidos’ €200m additional Term Loan B (TLB) from existing lenders5, the question then arises as to what credit risks lenders face over the medium term.

For now, substantial uncertainty remains over the shape of any recovery, and equally importantly, the shape of future demand. Lockdown has the potential to alter or accelerate demand trends; online shopping and working from home affecting demand for office space, facility services and wholesale support services such as catering are the most obvious candidates in potential changes to demand.

In our view, investors need to consider the outlook for the next few years as much as the immediate outlook for liquidity. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008‑09 led to the phrase “zombie” companies, where low interest rates enabled businesses to service debt burdens without ever being able to reduce them through free cash flow. This led to defaults being spread over many years with maturity and the inability to refinance being the triggers.

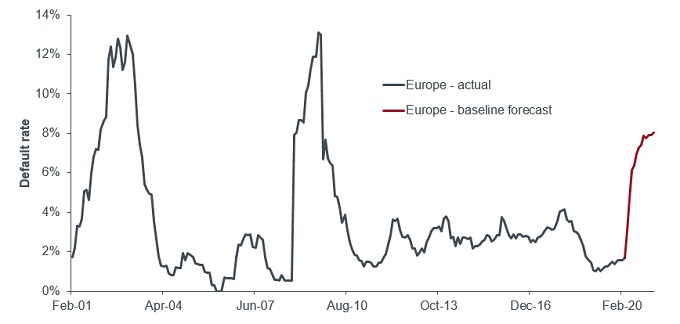

Chart 3: Moody’s default rates and forecast

Source: Moody’s speculative grade corporate default rates, as at 31 March 2020.

With so many companies taking on additional debt (some at eye‑watering amounts) without sharing the burden through equity raises, we fear that a number of companies may be left with unsustainable capital structures, leading to higher leverage for longer. This higher credit risk will translate into lower prices given the fixed margin on the borrower’s loan. Longer term, unless the business can grow into its enlarged balance sheet, defaults may rise when they need to refinance.

A key question is how much default risk is already priced into the loan market. The average price of the European loan market stood at 89.6 on 14th May6. Buying the market at a cash price of say 90 means an investor would need to experience a 20% default rate (assuming a 50% recovery) to take a hit to capital. In contrast, the percentage of the market trading at ‘stressed’ levels (cash price <80) totalled just 6%6.

In our view, default peaks will likely be smoothed given the substantial monetary and fiscal support being provided by multiple countries. The existence of loans, grants and cost support schemes seem likely to ensure defaults from liquidity shortages are significantly lower than would otherwise have been. On top of which, it looks like a high level of defaults are already priced into the market.

That said, with additional debt being taken on by many borrowers, and a number of companies facing a year of low or no earnings, credit metrics for many issuers will look ugly. We believe excess returns may be found in European loans; however, with increasing debt burdens and hence increasing credit risk combined with an uncertain demand picture, selectivity remains key.

Note:

References made to individual securities should not constitute or form part of any offer or solicitation to issue, sell, subscribe or purchase the security.

Footnotes: