May 2020

A negative fed funds rate: not yet willing – or needing – to go “there”

Nick Maroutsos

Nick Maroutsos

Head of Global Bonds | Portfolio Manager

Key takeaways

- We believe that the Federal Reserve would seek to exhaust other policy options before resorting to negative interest rates.

- Lower yields in the wake of interest rate cuts and Fed purchases have negatively impacted the risk/return profiles for bonds.

- Shorter-dated, investment-grade corporate credits are, in our view, one of the few pockets of the bond market likely able to provide steady income, capital preservation and low volatility.

Please see glossary of terms beneath article

As U.S. monetary policy ventures deeper into uncharted territory, the expectation that the Federal Reserve (Fed) will ultimately resort to negative interest rates has grown. For a brief period in early May, prices on fed funds futures signaled that the benchmark overnight rate could turn negative by early 2021. Fueling these predictions were collapsing employment, consumption and manufacturing data as the COVID-19 pandemic shut down large swaths of the U.S. economy.

We believe that negative rates in the U.S. are not imminent. Shaping our view are comments by none other than Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, who stated that the central bank has plenty of other tools to deploy before resorting to negative rates. He – among others – is also aware that in Japan and the eurozone, two regions that have already gone down the negative rate path, the measure has not been a panacea, failing to ignite growth or inflation. Furthermore, real interest rates – those upon which investment decisions are made – have been negative since early in the year. Given that economic activity tends to lag rate cuts, the Fed may want to assess future data before committing to even more unprecedented policy.

NEGATIVE RATES NO MAGIC BULLET FOR JAPAN OR EUROZONE

Even after adopting a negative interest rate policy, neither Japan nor the eurozone has been able to spur inflation or economic growth.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 15 May 2020

An unexpectedly large toolkit

As evidenced by his actions over the past few months, Mr. Powell appears to be a man of his word. The Fed has increased its balance sheet by 66% this year, purchasing Treasuries, mortgage securities, investment-grade and even select high-yield corporate debt. We have little doubt that he has additional levers to pull to support the economy.

In addition to increasing the amount of its purchases, the Fed can continue to expand the breadth of its programs with the aim of aiding the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic as well as those with limited – or no – access to credit markets. Another card up its sleeve may be yield curve control (YCC), a program that seeks to keep certain segments of the yield curve within a defined band. Should the Fed go down this route, we believe YCC would target the front end of the curve, with the aim of maintaining favorable conditions for the large number of corporate borrowers that tend to issue debt in the three -to five-year range.

Fiscal support playing its part – for now

For much of the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) era, Fed officials have consistently advised that monetary policy cannot go it alone and that governments must do their share by ratcheting up fiscal stimulus. In the wake of the massive programs signed into law as portions of the U.S. economy shut down, it’s hard to argue that elected officials have not met the challenge. But we believe that more is likely to be done. Lacking the immediacy of the past few months, additional fiscal measures may take more time to be enacted, but absent certainty on the duration of the pandemic and how consumer and business behavior may permanently change, we believe the government will be forced to take further steps to support fragile businesses and industries.

The travails of a bond investor in a low-yielding world

The newest round of quantitative easing and low interest rates create formidable challenges for fixed income investors. With the Fed’s open-ended commitment to purchase Treasuries and other assets, a bond investor’s core tenet of capital preservation appears intact. The objective of income streams commensurate with the level of risk incurred, however, may prove more elusive, continuing a trend that has lasted for most of the post-GFC era. For example, in the decade through December 2007, a 122 basis point (bps) increase in interest rates would have been required to wipe out the annual yield on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. With yields having tumbled and duration remaining elevated, it would now take only a 24 bps rise in rates to eliminate the year’s expected yield.

For investment-grade corporate debt, the bar for eliminating a year’s returns is a 33 bps rate increase.1 While intermediate corporates register a slightly better hurdle of 49 bps2, corporate debt in the one- to three-year range has a larger cushion of 82 bps3.

All roads lead to the front end

With this in mind, we believe the incremental return one may earn by venturing farther out along the yield curve is not worth the additional risk. Granted, we don’t foresee a sell-off in longer-dated securities given low growth, scant inflation and the Fed’s commitment to low rates, but the comparable returns on shorter-dated bonds, along with their lower volatility and greater liquidity, create a compelling argument that the front end of the curve is, at present, the natural home for investors seeking the traditional characteristics expected of bonds.

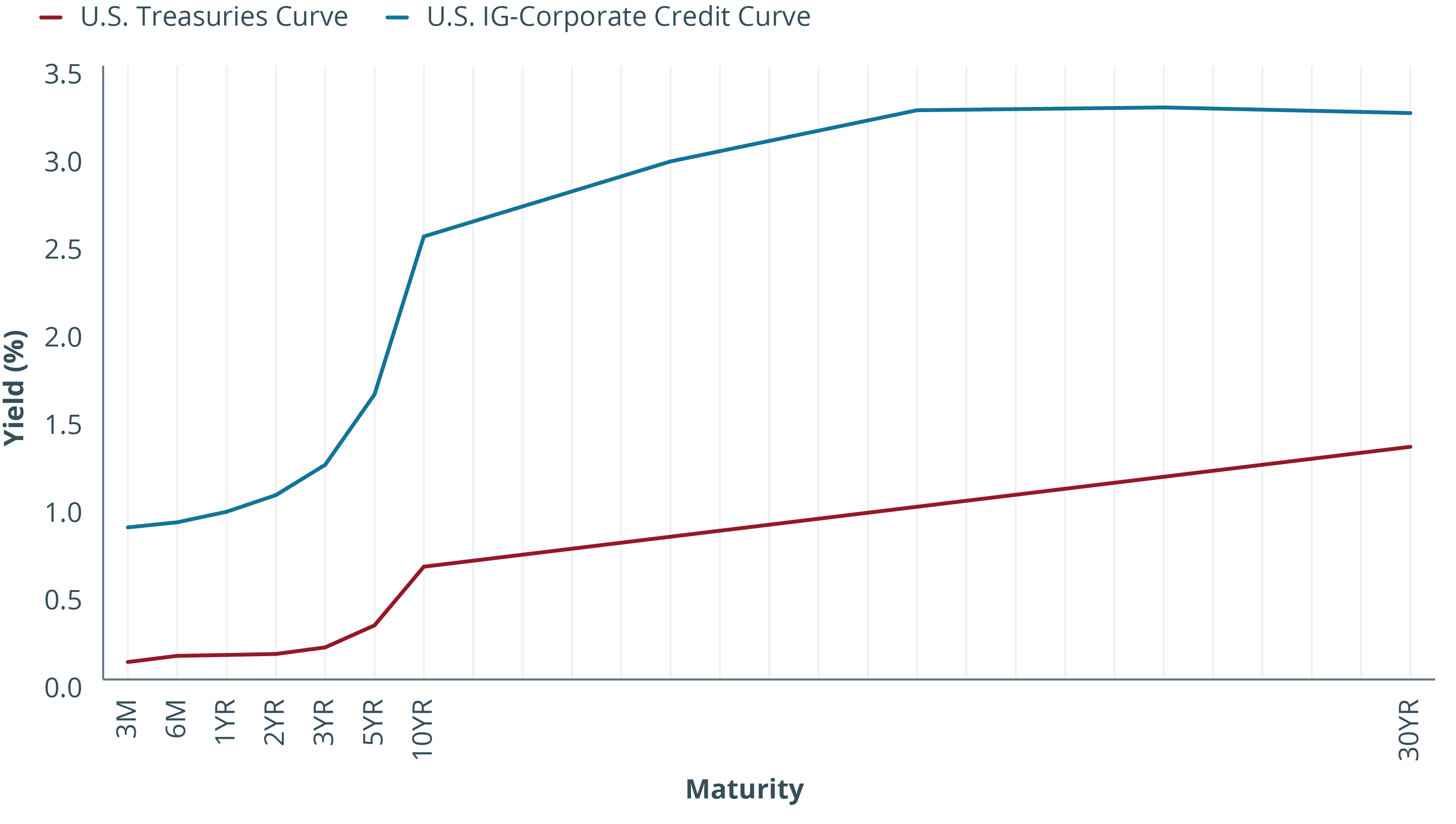

U.S. TREASURIES AND INVESTMENT-GRADE CORPORATE CURVES

Shorter-dated debt contains nearly all the yield of longer-dated securities, and corporates have the added benefit of higher yields over Treasuries even as the Fed supports the investment-grade credit market.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 15 May 2020.

While investors don’t give up much in potential returns by concentrating on the front end of the curve, yields here – especially for Treasuries – are exceptionally low. One can navigate that, however, by focusing on investment-grade corporates, which are now directly supported by Fed purchases. We don’t go as far as others by saying “the investment-grade corporate curve is the new Treasuries curve” but with its more pronounced term premium – along with its imbedded risk premium – shorter-dated corporates, in our view, offer some of the most attractive risk/return profiles in today’s still-uncertain markets.

1 Based on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index measures the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market.

2 Based on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Intermediate Corporate Bond Index. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Intermediate Corporate Bond Index measures the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market whose maturity ranges between 1 to 9.9999 years.

3 Based on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate 1-3 Year Index. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate 1-3 Year Index measures the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate, taxable corporate bond market with 1-3 year maturities.

Glossary

Investment-grade corporate bond A bond typically issued by companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments. The higher quality of these bonds is reflected in their higher credit ratings when compared with bonds thought to have a higher risk of default, such as high-yield bonds.

High-yield corporate bond A bond that has a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond. Sometimes known as a sub-investment grade bond. These bonds carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher coupon to compensate for the additional risk.

Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based measure of the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

FIXED INCOME PERSPECTIVES

More Fixed Income Perspectives

Previous Article

The long-term opportunity in structured securities

The Structured Securities team discusses its positive long-term outlook for U.S. structured securities in higher-quality, seasoned and shorter-dated exposures.

Previous Article

Are near-term debt levels a distraction?

Credit portfolio managers John Lloyd and Tim Winstone argue that markets are fixated with the near-term expansion in debt levels when a deeper look at credit fundamentals shows a more nuanced picture.

Next Article

Taking higher-quality risk in core plus bond portfolios

Greg Wilensky, Head of U.S. Fixed Income, discusses the importance of identifying and diversifying risk factors in bond portfolios.