Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

With the yields on short-dated investments very low or negative in Europe, managers of the Janus Henderson Absolute Return Income strategy explain how moving along the risk spectrum into an actively-managed, low volatility fixed income strategy could be a potential solution for investors seeking to make their defensive assets work harder over the medium term.

Key takeaways

The temptation when faced with uncertainty is to do nothing. It is not a bad strategy per se. In fact, in the world of football, when faced with penalties, goalkeepers who stayed in the middle of the goal would potentially save more penalties than those who dive to one side or the other.1 Yet goalkeepers feel less bad (and fans are potentially more forgiving) when they appear to be doing something even when it may not be optimal.

For savers and investors, the equivalent of doing nothing is holding cash. Again, it is not a bad strategy. In fact, the first rule of investing is to hold sufficient cash to fall back on in time of need. Yet is it optimal?

Nick Maroutsos, one of the portfolio managers on the Janus Henderson Absolute Return Income strategy, sees an important role for cash but believes that holding too much in today’s environment can be sub-optimal. “For most investors, whether you are in the US, the UK, or the eurozone, it is hard to get a real return on your cash. Inflation is effectively eroding the value of your savings.”

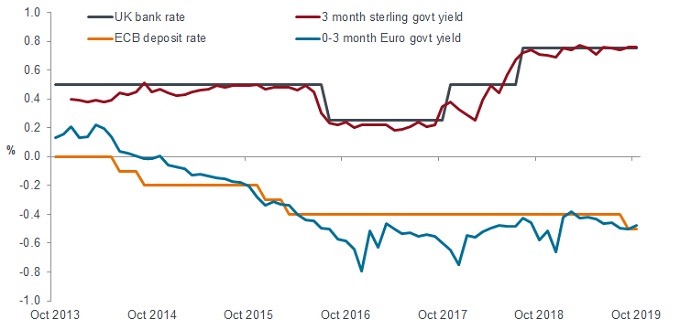

For bigger and wealthier investors in Europe, the outlook for cash returns is bleak as central bankers impose ever lower interest rates. Institutions will typically receive rates close to central bank policy rates, less an agreed sum, so for UK investors that means around 0.75% while for eurozone investors the figure is negative and close to -0.5% at 26 November 20192. In Switzerland, negative interest rates are even being applied to very large household deposits and not just to institutional clients. In such instances, doing nothing means seeing your cash shrink, not just in real terms but in nominal terms too.

Source: Refinitiv, interest rates of Bank of England Bank Rate and ECB deposit facility rate; Bloomberg, yields to worst of ICE BofAML 3 month Sterling Government Bill Index and Bloomberg Barclays Euro Treasury Bill 0-3 month Index. Yields may vary and are not guaranteed.

Investors have plenty of reasons for seeking to allocate capital conservatively. The US-China trade war has dampened an already anaemic global economic growth outlook, while geopolitical risks such as Middle East tensions and Brexit are on investors’ minds. Nick recognises the challenge: “You can’t blame investors for wanting to protect their capital. Equity markets are near all-time highs, so the threat of a correction is a real possibility. But where do they turn to when supposedly safe government bonds have low or negative yields and cash rates are so low?”

Nick believes there is a middle ground where investors can make their defensive assets work harder. In his view, applying an absolute return approach to a fixed income portfolio can help: “By expanding their universe, we believe investors can uncover opportunities that offer potentially higher returns than short-term cash-like instruments, without assuming excessive risk”

At the heart of the Janus Henderson Absolute Return Income strategy is a team driven by an absolute return mindset. “A focus on preserving capital is pervasive to our decision-making so we constantly evaluate how much we are comfortable to invest and at what risk,” explains Nick. “Once this is determined, the unconstrained nature of the strategy allows us to seek the best-adjusted returns from around the world, fine-tuning the portfolio – typically using derivatives – to help mitigate risks and enhance returns.”

The portfolio comprises a core of actively managed fixed income securities (which they call the yield foundation) and a carefully selected group of trading ideas (deemed structural alpha).

While the strategy is able to invest anywhere in fixed income, the managers have self-imposed limitations. They aim to keep annual volatility below 1.5% and duration is typically kept between -2 and +2 years to prevent the portfolio from carrying too much interest rate risk. Sub-investment grade debt and emerging market debt is never above 15% of the portfolio and, in practice, rarely goes above 5%.

“Ultimately, we want to deliver consistent returns to investors with low volatility. You won’t find us chasing yield by going down to the risky end of the credit spectrum. It is all about building incremental gains,” says Nick.

What makes the team stand out is their willingness to be truly global. With managers based in California and Australia, together with broader input from Denver and London, the team are not afraid to be geographically different with their holdings. Currently, this means having very little exposure to Europe, and a bigger presence in the US and developed Asia-Pacific markets.

“In our view, investors are just not getting paid to hold whole swathes of the European bond market,” says Dan Siluk, co-manager on the strategy.

To support his argument, he points out that yields and credit spreads on European banks are being compressed by quantitative easing. “Why own a bond issued by a European bank in euros or sterling when we can potentially get a better spread pick-up by holding one of its bonds issued in Australian dollars and taking advantage of the interest rate differential between the two countries? We can hedge the currency risk so that we’re not taking any extra default risk as it is the same underlying company that is paying the coupon on the bond.”

Although they can take very small bets on currency, nearly all the bonds held are hedged back to base currency. Derivatives, when used, are typically for dampening risk, such as using interest rate futures to manage duration and credit default swaps to manage credit risk.

The co-managers have seen their fair share of credit and economic cycles. In fact, assessment of the macroeconomic and technical outlook is a key part of their investment process; they are guided by a sub-12 month outlook given that near-term risks are a bigger influence on volatility, and carefully monitor liquidity and correlations.

For now, the team’s focus is on finding jurisdictions with positive real yields or where they can exploit the yield curve. Jason England, co-manager, remarks: “Even where sovereign yield curves might be inverted, the corporate credit curve in a country can often be positively sloped, so we can get some roll-down3 by investing in the front end of the credit curve.”

Capital preservation is not guaranteed. Holdings will vary over time.

1Source: Journal of Economic Psychology, Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: The case of penalty kicks. Michael Bar-Eli, Ofer H Azar, Ilana Ritov, Yael keidar-Levin, Galit Schein, 2006.

2Source: Bank of England, European Central Bank

3If you buy a longer-term bond and the yield curve has a normal upward slope, the market price of a bond increases as the bond rolls down the yield curve. For example, imagine buying a 2-year bond, paying a 3% coupon with a 3% yield – the bond is priced at face value of 100. After a year, you effectively own a 1-year bond. If rates have not changed, the market yield on a 1-year bond should be lower because it is a shorter-term bond. Your bond still pays 3% but the market yield for a 1-year bond is say 2%. An investor would be prepared to pay 101 for your bond. The bond has gained value as it rolled down the yield curve.