Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Roll the clock forward to present and at a recent US conference the same message was once again repeated. While I agree that bond markets have been frozen at the seventh inning, I would expand it by saying that we have been there for some time. It is a phenomenon that is also true for developed market interest rates, economic growth and inflation.

The debt clock, showing the four stages of a credit cycle – downturn, credit repair, recovery and expansion (late cycle) – seems to be stuck at the ‘expansion/late cycle’ phase. Although the clock in the US is slowly beginning to move, Europe’s clock is broken. Overall, we seem to be in the midst of a very slow moving cycle (arguably even going backwards at times), which may turn out to be the longest in recent history.

And it is not just the credit cycle that seems to have become stuck; the same is true of interest rates, economic growth, inflation and default cycles. In a well-behaved world, business cycles follow the pattern of growth, boom, recession and recovery. In the boom phase, excess demand leads to rising inflation, which in turn translates into higher interest rates to dampen the demand.

The recent period of recovery has naturally led to reflation¹ theories. However, while there is evidence of an uptick in headline inflation, core inflation (excluding volatile items such as food and energy) remains subdued. There is also evidence that a mild slowdown in economic activity in China and the US will likely emerge around summer.

The uptick in inflation and economic activity has occurred in response to a number of factors including a loosening of monetary policy² in China about a year earlier, sparking a rally in commodities which helped produce better economic data in the developed world since the middle of last summer.

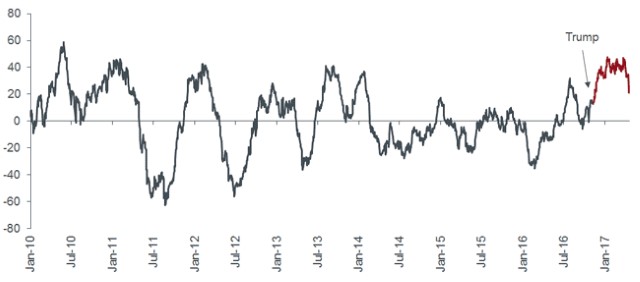

Thus, markets began to move from last June and trading strategies switched to those favouring equities over bonds. Later, the view that growth and inflation are likely to rise based on a Trump presidency, bumped sentiment higher. The ‘Trump effect’ was just fortunate timing – no doubt the President will take the credit for it.

However, this does not indicate a regime change in our view. It is essential not to confuse the China-induced cyclical upturn with the longer term structural issues that still persist in the global economy. We have long talked about a number of structural forces that are keeping growth and (core) inflation low. Among those are adverse demographic trends (not enough producers/consumers and too many old savers), lack of productivity, disruptive technology, digitalisation, a global savings glut and behavioural changes.

Now, the latest data suggest that the cyclical uplift underway pre-Trump’s election is stalling. The chart below shows economic surprises have turned down as expected.

G10 Citi Surprise Index

[caption id=”attachment_252802″ align=”alignnone” width=”640″]

Source: Bloomberg, as at 20 April 2017

Note: The Group of Ten (G10) is made up of eleven industrial countries (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States), which consult and co-operate on economic, monetary and financial matters.[/caption]

The longer term structural forces continue to challenge monetary policy in the developed world, which has been kept loose in recent years to encourage economic growth. But how much longer can it be maintained?

There is a global phenomenon that is likely to have profound effects on monetary policy and central banks’ ability to adjust economic growth (through interest rates) in the future. It has a little economic symbol – r*. r* is the natural or equilibrium rate of interest when real gross domestic product (GDP) is growing at its trend rate and inflation is stable.

Studies have shown³ that over the last quarter of a century there has been a significant decline in r* across North America, the UK and Europe, reaching historically low levels in the recent past. The underlying cause is the structural factors mentioned earlier, which appear poised to stay.

Thus, it looks like r* will remain at low levels in the future (by extension implying lower growth and lower inflation). This is particularly important; as while central banks can set interest rates to influence the economy, r* is a function of the economy and beyond their sphere of influence.

What does this mean in practice? As an example, even if the US Federal Reserve (Fed) was to hike rates a few times, it would not heavily influence economic activity/data. In fact, the very latest hike in the US referred to as a ‘dovish hike’ led to lower government bond yields (higher prices) as long maturity bonds rallied, doubting the reflation theory. This is another example showing that while equity markets follow soft economic data such as surveys and sentiment indicators, the bond markets concentrate on the hard economic facts.

And while the Fed seems poised to increase rates, can it really decouple its monetary policy stance from the rest of the world? Judging by the experience of other central banks that have tried in the past but were forced by economic circumstances to reverse policy soon after (Sweden in 2010, European Central Bank in 2011), there is reasonable doubt.

Another important benchmark for central banks in gauging the state of the business cycle, the outlook for future inflation and the appropriate stance of monetary policy is the NAIRU4. This is the unemployment rate consistent with a steady level of inflation in the near future. In simple terms, inflation will tend to rise if the unemployment rate falls below NAIRU (due to rising wage pressures) and vice versa.

Interestingly, the Bank of England has recently lowered its view on where NAIRU is, since wage inflation is not as strong as expected for the current level of unemployment. With limited evidence of wage inflation in the US, could they follow suit?

Given historically low yields in fixed income markets, many have sought alternative investments such as over-leveraged6structured products7, peer-to-peer lending8, infrastructure9and private placements10in a bid to find extra returns. In addition, with the stock market’s current upbeat assessment of growth and inflation, almost universally, many are short11duration (interest rate sensitivity) and underweight gilts.

In our view, one should remain wary of the illiquid alternatives; they have inherently more risk and are not necessarily suitable for all clients. Carry, or the coupon income, may sound rather dull but it is the most sensible route to seeking long-term returns in an uncertain world. Thus, we stay true to our mantra of sensible income from large-cap, non-cyclical businesses that have a reason to exist in the economy.

Our current asset allocation thoughts are that investment grade corporate bonds are becoming more interesting and while we still like high yield bonds, we find the appeal of secured loans12to be fading. In the near future, there is of course potential for risk off episodes, but this is unlikely to come from within the credit markets; most likely external factors such as European politics will upset risk sentiment.

The bond markets’ seventh inning stretch could last a long time in the low growth, low inflation world that we live in. Let carry be your friend.