October 2019

The perceived lunacy of negative yields

Strategic Fixed Income

John Pattullo

John Pattullo

Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income | Portfolio Manager

John Pattullo, Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income, explores the phenomenon of negative-yielding bonds: how they came about, why anyone might buy them and whether they are here to stay.

Key Takeaways

- Huge growth of negative-yielding debt has triggered a predictably simplistic narrative about bond bubbles.

- Negative interest rates are a logical symptom of a deep structural malaise in those countries that are experiencing them and a flawed policy response – an overreliance on monetary policy and, political impediments to fiscal spending. Richard Koo provides the framework for this economic stagnation through his “balance sheet recession” framework. It will be slow to change.

- Negative-yielding government bonds are attractive for investors in countries with positive interest rates (ie, America) after the currency hedging benefit is taken into account. They often yield more than the government bonds in their domestic economies.

- It is therefore attractive for foreigners to buy these bonds for their return profile. Domestic investors are forced buyers for reasons of negative bank deposit rates and regulations.

Creeping march of a bizarre asset class

It has been said that the bond markets have entered a financial twilight zone with no obvious way out. In August, Germany issued its first 30-year zero coupon bond (it had already issued a negative-yielding 10-year bond with zero coupon in July), which means that you are certain to get back less than you paid if you hold the bond to maturity. Elsewhere in Europe, as a late consequence of the negative interest rates, some banks in Switzerland and Denmark have begun taxing wealthy depositors to hold their money. One Danish bank has also become the first to offer a 10-year mortgage rate, where they seemingly pay the borrower 0.5% for taking out a loan!¹ (Where were they when I took out my mortgage?)

The proliferation of negative-yielding debt

Source: Bloomberg, data from 5 September 2018 to 5 September 2019

Note: Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Negative-Yielding Debt Market Value USD. Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based measure of the global investment grade fixed-rate debt markets.

At the end of August, $17 trillion of bonds around the globe – that is about a third of the tradeable bonds in the world – were trading with a negative yield, of which around $1 trillion were corporate bonds. By geography, the majority of this debt sits in Europe and Japan.

The huge growth of negative-yielding debt has triggered a predictably simplistic narrative about bond bubbles: “The bottom is in for bond yields … inflation is coming down the pipe”, CNBC Talking Heads tell us.

We could not disagree more.

How did we get to sub-zero yields?

The story began in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. Hoping to spur borrowing (that could lead to economic growth) and bring back inflation (which generally goes hand in hand with a strong economy), quantitative easing (QE) and monetary policies by global central banks sent interest rates cascading down and eventually into negative territory in some countries.

However, while they managed to inflate asset prices, higher inflation remained a challenge. The inability of QE to stoke normal inflation has meant that central banks have gone beyond the zero bound. In Europe, given the restriction of using fiscal policy, the central bank broke through the lower zero bound as it strived to equate savings and investments (the theory goes that if you lower rates enough, you will reach an equilibrium level where demand will pick up). Unfortunately, looking at the Japanese² experience, lowering rates only makes people save more and not borrow more. My colleague, Jenna Barnard, has talked about the lobster pot of QE – rates fall (in) but cannot climb back (up)! See economist Richard Koo’s article on how vanishing borrowers reveal the flaw of aggressive easing³.

In recent months fears for a dramatic global economic slowdown – primarily caused by the US Federal Reserve (Fed)’s overtightening policy but compounded by a slowing Chinese economy, the US‑China trade war, US tariffs on autos, and Brexit – have propelled investors towards safe‑haven assets, driving sovereign bond yields to extreme lows and even into negative territory.

Why buy a bond that pays you less in the end?

Buying a negative-yielding bond is not as illogical as it seems. So where is the logic?

- Expectations that yields will become even more negative — yields are still too high to equate savers and borrowers. With dovish signals from central banks, one can expect yields to become even more negative as interest rates are lowered further, so the bonds will rise in price. Additionally in Europe, with the European Central Bank’s revived asset purchase programme, there would be a ready buyer to take them off your hand.

- Favourable yield pickup to dollar based investors — negative-yielding government bonds are attractive for investors in countries with positive interest rates after the currency hedging benefit is taken into account, which makes them yield more than the government bonds in their domestic economies. It is therefore logical for foreigners to buy these bonds for their ‘return’ profile. Domestic investors, on the other hand, are forced buyers because of negative bank deposit rates and regulations⁴.

- Play the ‘steep’ negative yield curve — it is all relative to base rates; try not to think absolutely but relatively. If base rates are negative (meaning you will have to pay to keep a deposit at the bank), suddenly a corporate bond yielding one percent becomes an attractive option. A steep yield curve (ie, short-term rates lower than longer term rates), regardless of being negative, makes it possible to pick up yield.

- Potential for generating ‘positive’ real yields — depending on how far inflation will fall versus where it is currently, you can still generate a positive real yield. We retweeted an interesting note on this on 21 August on why buy a German 10-year bond at -0.6%.

- Asset/liability matching — if you need to match assets and liabilities in, say, 30 years’ time, at least you know the German government will repay you (university fees anyone?). Return of capital supersedes return on capital in these strange times.

Where is all this heading?

Our base case, for the last eight years, has been that the world is turning Japanese, struggling to find growth and/or inflation.

The reasons can be found in theories such as Richard Koo’s balance sheet recession, where individuals and corporates change their behaviour after a trauma of experiencing negative equity, preferring to save and pay down debt rather than borrow and consume. Larry Summers’ secular stagnation theory is another, where excessive savings act as a drag on demand, reducing growth.

There are other dynamics at work confounding growth and inflation, including factors such as the effects of globalisation, the transparency that the internet brings to pricing competitiveness, internet giant companies such as Amazon destroying the pricing power of others, demographic forces and new trends in employment such as zero hour contract work – all helping to push down prices and mute inflation.

In addition, we feel that since only low inflation could be generated, base rates have had to come below inflation to reflate the economies and reduce debt. This is financial repression by governments and one way to deleverage an economy (see our article in June: Do you remember the Global Financial Crisis?).

Further, the more recent dovish pivot by central banks has not only lowered interest rates further, but also resulted in lowering ‘real’ interest rate expectations. We still have woefully low business investment relative to the demand glut for savings. Thus the ‘neutral’⁵ real rate of interest remains too high. Most research today suggests that the real neutral rate should be around zero or possibly even negative (as it is in Europe and the UK).

Our expectations are that this trend will continue; base rates will go even lower and inflation expectation fall further. This is why gold bugs are frothing at the mouth, as lower real yields are positive for the gold price (gold could be considered quite ‘yieldy’ at zero!⁶). While the oil price rise is an unfortunate tax on the consumer, we now have inverted yield curves and a strong dollar. Added to this, a US central bank that is miles behind the curve on some bizarre concept that inflation is going to break out. Monetary policy is like pushing on a string and if the Fed does not cut very aggressively, very soon, they will not be able to steepen yield curves and reflate the economies.

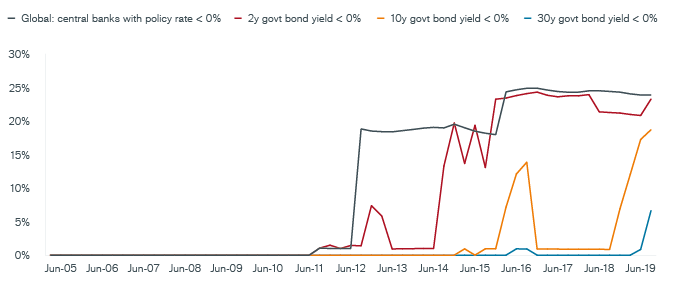

Sub-zero interest rates around the globe today

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch, The European Credit Strategist research report, 23 August 2019

Note: Quarterly data, percentage of world gross domestic product (GDP) with interest rates below zero

Negative yields are, then, here to stay

They are a consequence of negative interest rates, which themselves are a logical symptom of a deep structural malaise in countries that are experiencing them and the flawed policy response – an overreliance on monetary policy and, political impediments to fiscal spending.

Base rates will become more negative in the future as central banks try to steepen yield curves. In addition, they will continue repressing us to reduce debt levels. Financial repression and modern monetary theory (MMT) are the next paradigm shifts, so get ready.

A different ‘economic’ lens

We look at the world through a different lens. Sitting in Europe, looking at America through a Japanese lens, gives you a very different perspective on bond yields. While our esteemed competitors tell us bond valuations are off the charts, and so many have been in short duration and high yield assets, we have chosen very long duration and quality investment grade investments that have proven to be rewarding. We continue to think capital can be made, especially in Australia, the UK and America, and like quality large-cap US global titans who pay a positive real yield. The bonds of the latter will likely become even more scarce in the future as investors soak up their debt issues.

1 In practice, including the fees for the loan structure, there is still a positive cost to the borrower.

2 Japan’s near 30-year battle with deflation and anaemic growth as extraordinary but ineffective monetary policy stimulus saw bond yields hurtling lower.

3 Why aggressive monetary easing is pushing on a string. Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute. Financial Times. 10 September 2019.

4 Regulations such as asset/liability matching for pension funds and insurance companies.

5 Neutral rate: the rate at which monetary policy is neither contractionary nor expansionary; this is a rate that should exist when an economy is at full employment and has stable inflation. By setting benchmark rates above or below the neutral rate, central banks can cool or stimulate the economy.

6 There is a modest storage cost to factor in.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Global Fixed Income Compass

More from Our Investment Professionals

Investment roundtable: Views on the global economic outlook

Our senior global bond portfolio managers respond to common investor questions on the global economic outlook. Low yield is not no yield: Opportunities in structured credit

Our structured credit team highlights attractive aspects of the securitized market, including relatively short durations, high-quality credit ratings and attractive yields.