Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Nearly everyone holds some cash in their portfolio - maybe we plan to invest it later, pay large expenses, or as a counterbalance to other risky investments we hold.

Often, we don’t really know how and when we plan to spend (or invest) it, so we want this cash to be accessible regardless of market conditions. The basic choice is a one-month Treasury bill, but really any Treasury instrument would do – they can be sold easily in case we need funds sooner than maturity.

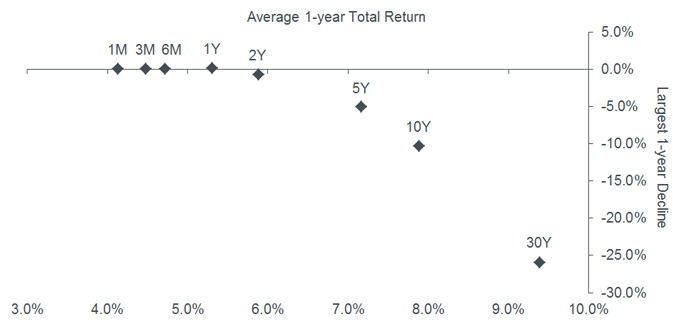

Storing cash in Treasuries avoids credit or liquidity risk, but does take duration risk – if rates rise, we might not get back what we paid. The main goal for reserves is maintaining cash value, but also getting the best possible return. The chart below compares the historical average one-year holding period return for each major Treasury maturity (1-month, 3-month, 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 5-year, 10-year and 30-year) versus its largest one-year decline.

Clearly, historical returns are well above current rates. Nevertheless, the graph shows that despite various periods of rising and falling rates over the last 37 years, holding 1 or 2-year Treasuries rather than shorter-term bills generally increased returns while taking minimal drawdown risk. Rate sensitivity for these maturities is low as hike expectations are mostly already priced in – the 2-year note today nearly fully reflects the rate profile implied by the Fed dot plot. So even if the Federal Reserve raised rates five times over the next two years, the total return from rolling 1-month bills versus buying a 2-year note now would likely be about the same. However, there is a potential asymmetry – if the Fed slowed its hiking pace due to falling markets/economic slowdown/moderating inflation, then the 2-year holder would be ahead.

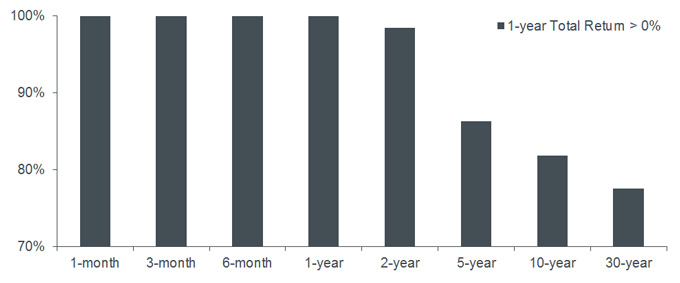

Rather than just the worst case drawdown (peak to trough decline over a period), another way to compare various Treasury maturities is the observed probability of achieving a positive total return over a 1-year holding period. Up to 2-years Treasury maturity the likelihood of a capital loss is very low, but the risk of a shortfall rises quickly as duration is extended out. Always holding a portfolio of 2-year bonds (versus rolling 1-month bills) has added, on average, 1.7% per year to returns. At today’s rates and with hikes anticipated, the potential benefit from extending is much smaller, but likely still flat or positive.

There is plentiful demand for short-term bills for legal, collateral, and other funding reasons. If an investor knows they need to spend the cash soon, then it makes sense to target a shorter maturity. But if they are holding cash reserves in 1-month bills mainly because they expect rates to rise a few times, then they are probably better off buying 1-2 year paper – the duration risk is largely offset by the extra yield.

By extending modestly, an investor can increase interest earned (e.g. for Treasuries, current 1-month rate is 1.48%, 2-year rate is 2.25%), with a very low risk of a loss in capital. They could also benefit if rates rose more slowly than currently anticipated.