Globalization: Sorry, Donald, It’s Here to Stay

Fixed Income Leadership

-

Jim Cielinski, CFA

Jim Cielinski, CFA

Global Head of Fixed Income

Global Head of Fixed Income Jim Cielinski discusses how attempts to push back on globalization could increase volatility and create a rocky path for investors.

Key Takeaways

- While trade wars and the ascent of populism suggest that we have moved past “peak globalization,” the underlying trends that have propelled it remain pervasive.

- Many of the ways in which globalization has played out – lower rates, lower inflation and wealth inequality – are here to stay.

- The clash between the trends that have defined the global economy in recent decades and the inequality that globalization creates will likely bring increased volatility in coming years and potentially upend the investment environment.

Globalization, one of the most important economic trends of the last century, has been taking more than a few shots recently. For those prematurely announcing its demise, the evidence may seem clear. The ascent of populism, Donald Trump’s election, Brexit and resurfacing trade wars are surely signs that we have moved past “peak globalization.” That conclusion is mistaken. The underlying trends that have propelled globalization remain pervasive. But we have seen the end of the period where these trends are universally viewed as positive, and we have seen the end of the period where all participants will sit by and watch passively. This friction is critical to understanding today’s new investment regime.

Globalization is a supertanker. It can change direction and perhaps even reverse course, but it takes a long time to do either. Trump and Brexit are akin to the lookout on the ship’s bridge shouting “rocks ahead.” We will not know for a while whether we have steered clear. In the meantime, hang on. Many of the trends that have driven the uprising against globalization are about to become even more entrenched.

A Win-Win, In Theory

Globalization is built on a foundation of the free flow of goods, capital and labor. This creates a win-win scenario. Growth, in aggregate, increases with greater global integration. Inflation, normally a worry in periods of faster growth, remains suppressed as production shifts from high-cost regions to low-cost regions. As low-cost producers produce more, their standard of living also grows, providing a self-reinforcing uplift to global consumption. More producers equates to more choices for consumers. Consumers benefit through a greater ability to substitute goods, further restraining price pressures and improving efficiency. In addition, the interdependencies fostered through global trade enhance international cooperation and communication. It’s all bliss, at least in theory.

What can go awry with such an ingenious plan? Plenty, it turns out. Importantly, the benefits of globalization accrue in aggregate, but they occur very unevenly. Winners and losers are evident across economies and within economies. History shows that the largest and strongest economies are often among the biggest winners. But so are the impoverished societies that are encouraged to produce and innovate: More than 1.2 billion people have moved out of extreme poverty since 1990. Owners of capital, however, easily outpace laborers. Low-skilled pools of labor in higher-priced production areas are the unambiguous losers. The rich – both countries and individuals – tend to get richer. This inequality engenders populist feelings in those left behind, who feel they are held back from globalization. They are correct, at least as it relates to their corner of an increasingly globalized world.

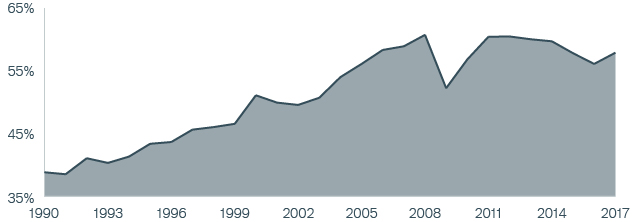

Global Trade Volume as a Percent of GDP

Globalization is built on the free flow of goods, capital and labor, and growth, in aggregate, increases with greater global integration. Over the last three decades, trade has grown along with global GDP.

Source: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files, data to 12/31/17. Trade is the sum of exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of gross domestic product.

Tariffs May Accentuate Globalization Trends, Not Curb Them

Evidence arrives daily to remind us that globalization is unstoppable. At the macro level, the twin deficits¹ in the U.S. are boosting the volumes of global capital movement and interdependency. At a more micro level, we see that expanded tariffs are nearly always short-circuited by global trends. For example, Apple and Foxconn have already announced that in the event of U.S. tariffs on Chinese-assembled iPhones, they have the capability to meet U.S. demand from other countries. The result will be further expansion of manufacturing capacity into economic segments already suffering from overcapacity. Production for U.S.-bound goods will be shifted to even lower-cost producers. In summary, tariffs on Chinese goods may accentuate the globalization trends we have witnessed in recent years rather than curb them. This same story will play out across the goods-producing sectors.

Trade wars are at the leading edge of the globalization debate. Many worry about the inflationary implications of a trade war that severely disrupts global supply chains. Here again, the evidence suggests otherwise. There is a fundamental difference between a change in the price level and a change in inflationary pressures. Inflation should be thought of as the annual rate of change in prices. A change in price level is different. If all companies paid a new 20% tariff on imported goods and immediately passed it on to consumers, it is indeed true that prices would rise. But if incomes remained static, consumers could afford less. Price levels will reset, but the ensuing path of inflation will actually be lower. Perversely, attempts to push back on globalization, only serve to reinforce the structural deflationary trends we are accustomed to.

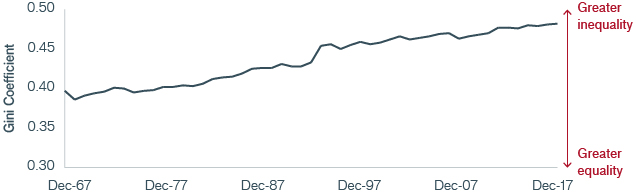

U.S. Income Inequality on the Rise

Globalization tends to help the rich, both countries and individuals, continue building wealth, and that inequality often engenders populist feelings in those left behind.

Source: Bloomberg, data to 12/31/17. The Gini coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A value of 0 represents perfect equality, a value of 1 (or 100%) represents perfect inequality.

A New Climate for Investors

Investors must adjust to this new climate. Many of the ways in which globalization has played out – lower rates, lower inflation, wealth inequality – are here to stay. The reaction function is now very different. The implications are critical to understand:

- Geopolitical risks will remain elevated

- The underlying trends of globalization won’t change, producing more rounds of populist backlash

- Developed economies will continue to lose market share as goods producers and will become more service-oriented

- Central banks will be very conscious of not over-tightening and committing a policy mistake

- Volatility in markets may well exceed the volatility of underlying fundamentals

Geopolitical risks represent genuine uncertainty. They are less predictable and analyzable than other risks, confounding markets. They tend to surprise us, demand immediate attention and usually lead to overreaction. Investors are advised to focus on those risks that are truly long-lasting and exploit the others, as they are typically short-lived. The key risk in this category is China. Investors must assess whether Trump’s end game is an attempt to level the playing field through tariffs or an attempt to derail China’s long-term challenge to rival the U.S. as an economic superpower. The latter will likely end badly for most risk assets.

More populist backlash is around the corner. The trends that led to populism remain ubiquitous, and thus populism isn’t going anywhere. This may take several forms. The right-leaning response relies on tax cuts and deregulation. The left-leaning response will rely more on spending and fiscal stimulus (hello, Modern Monetary Theory). Both are policy regime shifts that will materially alter market behavior.

Developed economies will become even more service-oriented. This may lead to a lower degree of cyclicality in developed economies. Assuming a lack of systemic leverage, this might be just the recipe for slower, but still positive, growth with diminished risks – the “Goldilocks” outcome.

Central banks are afraid. Inflation is low and growth is slowing. They have few tools in the toolbox. The U.S. Federal Reserve was the only large central bank to achieve monetary policy liftoff, and they did not get far before affirming that the real equilibrium level of real rates is lower than most thought. Central bank convergence is back on and, absent a recession, will be supportive for risk assets.

Market volatility is likely to be higher. This does not mean volatility will be persistently high, but it will be higher than what many are used to. And it will likely be more sporadic. Combine this with questions and concerns about market liquidity, and investors will need to be careful about not getting spooked as markets periodically trade in wide ranges.

Globalization is Alive, but Not Well

Globalization is very much alive. None of the trends that have defined the global economy and market behavior in recent decades are truly showing signs of reversal. But globalization is certainly not alive and well. It is taking the brunt of the blame for wealth inequality, the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector in many countries and immigration issues, among others. This is the clash that will help determine the investment backdrop in the next decade. Policymakers will meddle, and voters will speak loudly, electing officials who reflect their views on how to address the problems. Many of the actions will fail. Some will succeed. But nearly all of them will increase volatility and potentially upend the investment environment. Steer clear of the rocks.

1Twin deficits refers to the fact that the U.S. maintains both a fiscal deficit and a current account deficit.

Global Fixed Income Compass

Explore MoreMore from Our Investment Professionals

Downturn Implications and a Reconvergence of Rates

Jenna Barnard, Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income, explores the options for meaningful policy easing by developed market central banks in the face of the current downturn in global activity.

Convergence Returns to the Fore

Jim Cielinski, Global Head of Fixed Income, provides his perspective on some of the key macroeconomic factors that are driving fixed income markets.