Knowledge. Shared Blog

June 2019

Do You Remember the Global Financial Crisis?

-

John Pattullo

John Pattullo

Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income | Portfolio Manager

After quantitative easing (QE) failed to generate sustainable growth or inflation, the dial has turned to fiscal policy. John Pattullo, Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income, argues that a successful formula must combine fiscal and monetary policies, as well as structural reform.

Key Takeaways

- Most countries have more debt now versus 11 years ago (at the start of the Global Financial Crisis).

- We believe that monetary policies used to combat the crisis were inadequate and should have been combined with fiscal policies and structural reform.

- Fiscal policy can be effective if credibly financed and used at the right time in the cycle, but it must be invested and not consumed.

What Crisis?

“Do you remember the Global Financial Crisis?” Ahh, you mean the one we are still in…

It is rather amusing that we sometimes get asked the above question. We think some investors need to be reminded that we are very much still in the crisis.

The crisis happened for a number of reasons, but it was primarily the result of the enormous amounts of debt raised by households, corporations and governments. Hence, a lot of the economic “growth” prior to the crisis was financed by increasing debt in an unsustainable way. Remember the “Great Moderation?”1 Hmm…

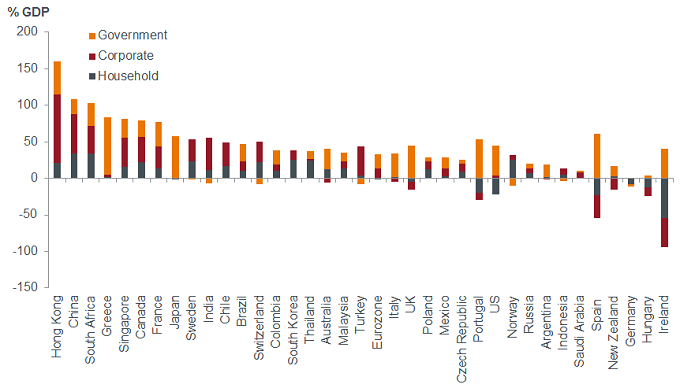

Eleven years on, as the chart below demonstrates, the vast majority of countries have more debt than before the crisis began – although a few have managed to partially reduce their debt. So, how on earth can the crisis be over?

Debt Loads Higher than Pre-Crisis

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, BIS. Change in aggregate debt, 2008 versus 2018, annual, as of 12/31/18. GDP stands for Gross Domestic Product. Note: Aggregates for household, corporate and government.

There are no easy solutions to reducing too much debt. A number of options are available, such as growth and inflation (which are hard to come by), austerity, default and/or financial repression2 (more on this later). But the not-so-distant past may hold lessons that can help.

Japanification Alert!

It was back in 2011 that we started talking about economist Richard Koo’s balance sheet recession thesis.3 It is extraordinary how reading one book (The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics: Lessons from Japan’s Great Recession, 2009) can completely change your view on economics and the bond markets.

In 2009, Mr. Koo prophetically forecast that Europe would turn Japanese. We have talked about this for years, but it is only recently that our inboxes have been flooded with “Japanification” articles on Europe. This backdrop explains why, throughout most of this period, we have favored much longer duration than many in our peer group, given our rejection of mainstream conventional economics.

Rather bizarrely, we are pleased to get some pushback on our views, which suggests there is still money to be made in bonds. Some investors remain short of duration or have tried their luck diversifying into alternatives away from quality, long-duration bonds. Many others, though, agree with our disinflationary outlook.

We feel that long-term secular drivers, such as demographics, technology, excessive debt and low productivity, will dominate and lead to lower global bond yields. We doubt that we can sustainably break out into higher inflation and growth, but that doesn’t mean that politicians, with a democratic mandate, could try something completely different (more on this later).

“Wot No Growth, Wot No Inflation?”

Below is the title slide from our 2013 New Year conference presentation (“wot” is an informal British version of “what”). In the presentation, we highlighted how small the money multiplier could be compared to the fiscal multiplier in a severely depressed economy. Our message was that fiscal policy tools should be employed to restore growth, but there was no political will at the time for such measures.

Our 2013 Presentation Cover — Still Relevant Today?

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, January 2013

The Global Financial Crisis was no ordinary recession; this was a “balance sheet” recession whereby individuals and corporations changed their behavior toward borrowing and spending after the trauma of experiencing negative equity. In such circumstances, lowering interest rates does no good and policies focusing heavily on the monetary side may not be effective, as we have seen.

Monetary policy broadly became independent in the 1990s in many countries, with the aim of taking politics out of the business cycle. Keynesian fiscal expansion was pretty much dismissed by conventional economists during this period as being ineffective. As the dogmatic Maastricht Treaty removed the possibility of fiscal expansion in Europe, the “one-clubbed golfer” of independent interest rates seemed to be the only policy tool.

While it is true that quantitative easing (QE) has massively expanded the monetary base, as Mr. Koo demonstrates, it completely decoupled from the growth in bank lending and money supply. As a result, we have created asset price inflation in Wall Street with no trickle-down effect to Main Street. The palliative needed was something along the lines of the “Koo Theory.”

Koo Theory

In Koo Theory, the government needs to borrow all the private-sector surplus and redistribute it via fiscal policy to stop the economy from shrinking into oblivion. This is very much in line with the secular stagnation4/excessive savings hypothesis of American economist Larry Summers. Unfortunately, European policymakers do not subscribe to the Koo thesis. And if the surplus is not redistributed, you get a deficit of demand and deflation — anyone mention Europe?

Why, then, was monetary policy not combined with fiscal policy? Surely, they should be complementary and not treated as substitutes. Italy, for example, would have welcomed (and still welcomes) a massive fiscal expansion (even though the Maastricht Treaty prevents it). As Mr. Koo points out, you also need structural reform before undertaking fiscal expansion, otherwise the effort will fail. Indeed, he said that 80% of the necessary change is structural reform, followed by fiscal expansion. (Note that this third arrow of structural reform was never delivered in Japan.)

Somewhat ironically, the inequality brought about by QE has led to the populist backlash in developed economies as well as calls for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)5/fiscal expansion – but let’s not confuse the two for now.

What’s all this MMT Chatter, Anyway?

MMT is really just a politicization of fiscal spending with unlimited constraint. No one constrained the British and the American fiscal expansion in World War II: tanks and warships were needed, so they were made. The idea was that governments spend as much as needed to achieve the desired outcome and worry about financing the deficit at a later stage.

So, after the abject failure of QE to generate any sustainable growth or inflation, the political dial has turned to fiscal policy. Now, governments are always keen to inflate away their debt by running inflation higher than the nominal yield on the debt that they issue. This policy – called financial repression – is one way to deleverage an economy (i.e., reduce debt). Interestingly, the reduction in debt generally happens via growth in the economy (i.e., higher Gross Domestic Product), which reduces the debt as a percentage of GDP, but rarely results in a reduction in the absolute level of debt.

Since only very low inflation could be generated, interest rates had to go even lower to try to reflate economies and enable negative real interest rates (to repress you and I!). Rest assured, further financial repression is both required and necessary to reduce global debt levels, but the current rate of progress is too slow.

Times Are Different Now?

The economic downturn that we are in is unlikely to recover to previously normal levels. Given poor demographics and productivity, the future trend rate of growth in both the U.S. and UK is around 1.5% to 1.75%. We are in a different regime after the “heart attack” of 2008 – one of low growth, low inflation and increasing financial repression. As mentioned earlier, Mr. Koo has called for a wartime response on the fiscal side, as this is wartime economics, but currently no one has the political mandate to justify such a response – although things are changing fast.

So This Brings Us Back to MMT

The theory that a government cannot default on its debts if those debts were issued in its own currency is not new. There is also a vast amount of economic literature on whether fiscal deficits matter. Still, this is certainty getting a big (political) push nowadays.

It is hard to argue that significant expansion in infrastructure, housing, technology, transport and education would not boost the economy, and it would surely have a much bigger multiplier effect than QE. The tricky bit is how it is financed and the potential repression (redistribution) of wealth that goes with it. Could such a stimulus offset long-term secular drivers? Possibly, but we are not convinced.

In Mr. Koo’s words, “MMT proponents are correct in arguing we need enough fiscal stimuli to absorb the private-sector savings surplus. However, this does not necessarily mean we need the central bank to directly finance the stimulus.”6 This is a key point in the MMT debate, which many people confuse: The stimulus should be funded from a private sector savings surplus, not by the central bank.

So What Will Work?

We have sympathy for fiscal, monetary and structural reform working together but say no to MMT if badly financed. It is the combination of these factors that is key.

Fiscal policy can be effective if credibly financed and used at the right time in the cycle. Further, it must be invested and not consumed. Debate continues about the financing angle with regard to MMT, much of which is political and highly ideological (the heterodox school of economics), to which this is no definitive answer. Politics may also throw a wrench in the works as to the effectiveness (or credible financing) of a fiscal expansion.

Approach and Positioning

We are mindful of MMT risk and think investors should be very selective by company and country with their investments. In our opinion, U.S. bond yields are inexpensive and, as real yields are positive, there is still capital to be made in U.S. bond markets as that economy slowly turns Japanese. The UK and parts of Europe already have negative real yields (we are being repressed slowly). Consequently, in the current environment, we think U.S. corporate and government bonds, as well as Australian sovereign bonds, are well positioned. Short-term cyclical swings, such as the two-year Trump reflation trade, can confuse the narrative. But overall, we continue to believe that most developed world bond yields are heading lower.

1 A period of economic stability characterized by low inflation, positive economic growth and the belief that the boom and bust cycles had been overcome. In the UK it generally refers to the period between 1993 and 2007.

2 In simple terms, using regulations and policies to force down interest rates below the rate of inflation; also known as a ‘stealth tax’ that rewards debtors but punishes savers.

3 Said to occur when high levels of private sector debt cause individuals and/or companies to focus on saving by paying down debt rather than spending or investing, which in turn results in slow economic growth or even decline. The term is attributed to the economist, Richard Koo.4 A prolonged period of low or no economic growth within an economy (excessive savings act as a drag on demand, reducing economic growth and inflation).

5 An unorthodox approach to economic management, which in simple terms argues that countries that issue their own currencies can “never run out of money” the way people or businesses can. In other words, governments that have control of the monetary policy are not constrained by tax revenues for their spending. Developed in the 1990s, it has recently become a major topic of debate among U.S. Democrats and economists.

6 Nomura, Richard Koo, Research Paper Titled: “MMT and the EU’s growing sense of crisis”, April 23, 2019. Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market

Knowledge. Shared

Blog

Back to all Blog Posts

Subscribe for relevant insights delivered straight to your inbox

I want to subscribe