Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Aneet Chachra, portfolio manager within the Alternatives team, asks whether fund flows affect equity prices.

On 2 January, Apple announced its Q4 results would be weaker than expected. Apple shares were halted at 4:30pm New York time (well after the official 4pm market close), the press release came out, and shares resumed trading at 4:50pm. Large asset managers rarely trade after-hours. But a few investors quickly evaluated this new information and the price of Apple stock immediately reset about 8% lower. Four million shares traded that night, only around 0.1% of Apple’s outstanding shares. But this was enough to determine the “correct” new market price and Apple shares the next day traded roughly in line with the after-hours price.

The logical conclusion is that a small number of active traders can interpret news, and everyone else can transact at a “fair” price. Theoretically, fund flows shouldn’t matter as every buyer is matched with a seller, and vice-versa. For every fund selling shares to increase cash, there is another fund or market participant reducing cash by buying the same shares. However, there is an observable relationship between net fund flows (in both directions) and concurrent market moves. Empirically, fund flows do matter.

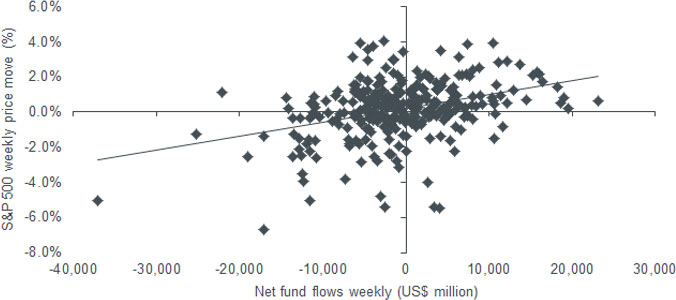

When money comes into an exchange traded fund (ETF) resulting in unit creation, the manager (or intermediary) needs to “put cash to work”, and when redemptions happen, needs to “raise cash”. Mutual funds and other institutions often have more discretion, but the same general forces still apply. All are likely transacting with counterparties that need to be induced via price to buy or sell. Figure 1 below compares weekly net fund flows into US equities (ETFs and mutual funds) to weekly price changes in the S&P 500 index. There is a positive correlation that is especially visible at the extremes. Inflows typically correspond to upward price moves over the same week, and vice-versa.

Figure 1: Weekly S&P 500 price move (%) vs net fund flows (US$ million)

Source: ICI, Bloomberg, weekly data from January 2013 to December 2018

Past performance is not a guide to future performance

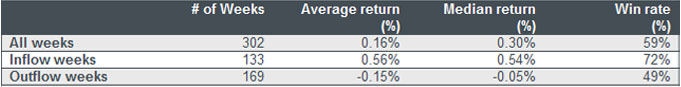

Bucketing illustrates this effect more clearly. All of the price gains (and more) over the last six years have come from weeks with net inflows – the S&P 500 rose in 72% of these weeks. Meanwhile, net outflow weeks were negative. Notably, average and median weekly returns were similar, so the difference was not greatly driven by outliers.

Source: ICI, Bloomberg, weekly data from January 2013 to December 2018

Past performance is not a guide to future performance

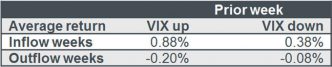

The relationship between flows and returns is also affected by the market environment. After expected volatility rises, the flow/return effect tends to be stronger in both directions. This makes intuitive sense – when volatility is falling, flows in either direction are more easily absorbed with a smaller and less predictable impact. But when fear dominates, flow imbalances create more price pressure.

We can proxy this by looking at the change in the VIX (volatility index) over the week before, and then looking at the impact of flow on return during the subsequent week. So there are now four categories – average inflow/outflow week returns conditional on whether VIX was up/down the prior week.

Source: ICI, Bloomberg, CBOE VIX (Volatility Index), weekly data from January 2013 to December 2018

Past performance is not a guide to future performance

Following higher volatility, inflow weeks have the best returns, but outflow weeks have the worst returns. When volatility has fallen, flow still matters but the difference is somewhat smaller.

Although a handful of nimble players might be able to incorporate news into price rapidly, subsequent pricing is not static. The direction of net fund flows appears to impact price and this effect is heightened when volatility is rising. It’s likely these fund flows are mediated via price-sensitive buyers and sellers who absorb any imbalance by supplying cash (at a discount) or shares (at a premium).

Going with the herd has a cost. Funds and strategies that take the other side of price pressure can capture a corresponding additional return.