Sector Spotlight: Food and Beverage

Corporate Credit

-

Brad Smith

Brad Smith

Credit Analyst -

John Lloyd

John Lloyd

Co-Head of Global Credit Research | Portfolio Manager

Co-Head of Global Credit Research John Lloyd and Credit Analyst Brad Smith explain how shifting consumer habits are shaking up the food and beverage industry, creating the need for a selective approach when owning these traditionally defensive names.

Key Takeaways

- A generational shift in consumer habits is shaking up the food and beverage industry.

- With the industry’s challenges and some company missteps top of mind, many investors may overlook those entities willing to absorb near-term pain – in terms of higher leverage and increased investment – in order to better position themselves within the future marketplace.

- In the event of a downturn, the steady cash flow of these consumer staples should not be impacted; however, judicious company selection remains critical.

The stable cash flows offered by historically defensive food and beverage companies can prove enticing for fixed income investors, particularly in an extended credit cycle where the timing of a potential economic downturn is in question. But past is not necessarily prologue. Disruption brought on by technology and a new generation of consumers has upended food and beverage’s relatively conservative paradigm, and with it forced companies to adjust. Companies that have been slow to adapt are at risk, especially those that have overemphasized managing their balance sheet at the expense of reengineering their business models to adjust to the rapidly evolving marketplace. In the text that follows, we delve into industry trends, how various companies are tackling the industry’s evolution and the implications for fixed income investors.

Battered by Headwinds

The food and beverage industry has been battered by headwinds in recent years. Packaged food, the hallmark of large, legacy brands, has fallen out of favor. Today’s consumer tends to prefer natural and organic ingredients and fresh or ready-to-eat food options to the processed food of yesteryear. Another shift that has seemingly caught industry stalwarts flat-footed is private labels. These insurgents can offer comparable quality at a significant price discount and are thus taking market share from legacy brands. Retailers are applying further pressure as they adapt to shifting consumer preferences by reallocating shelf space to private labels, startup brands and fresh food options.

In addition, the staunch brand loyalty of previous generations is largely lost on millennials, who rely on – and are chiefly influenced by – digital communication channels that weren’t even available a decade ago. The pervasive use of the Internet, and with it, the emergence of new advertising mediums, has broken down the industry’s largest barrier to entry. Today, a startup needs only an Instagram account and a set of influencers, and a brand is born; gone is the need for store-to-store sales and billion dollar advertising campaigns. The Internet has also introduced new distribution channels, as shoppers increasingly opt for the convenience of door-step delivery.

Cutting Cost for Profit

Concurrent with the industry evolution has been a wide-spread adoption of zero-based budgeting (ZBB) – a planning approach in which the budget starts at zero each year and every expense must be justified annually. Whereas many players have focused on reinvesting cost savings into brand renovation and innovation to help combat industry disruption and keep margins stable, others such as Kraft-Heinz perhaps got a bit overzealous in their cost-cutting measures. The world’s fifth-largest food and beverage company and a large issuer of U.S. investment-grade credit has been the vanguard of focusing on profitability at the expense of nearly all else. Such misplaced priorities, in our view, are behind the company’s notable 4Q earnings miss and the recent $15.4 billion write-down in value of its best-known brands.

Brazilian private equity firm 3G Capital has long been a champion of ZBB and quickly implemented the practice at Kraft-Heinz, following its acquisitions of Heinz in 2013 and that of Kraft two years later. Through cost-cutting measures, Kraft-Heinz increased operating margins from 14.4% in 2015 to 23.2% in 2016, and continued to put focus there. But there can be too much of a good thing. By our estimates, its first 4% of margin improvement created long-lasting efficiencies. However, with operating margins roughly 10% higher than the industry average, the company appears to have been overearning post-merger.

The Fallout

In one respect, management was achieving its objective – and handsomely. But the other side of that coin was a failure to reinvest gains back into its brands, an incredibly important step given the significant shift in industry trends. With many of the company’s “go-to” brands no longer holding the same power over consumers that they once enjoyed, Kraft-Heinz was forced to reduce the goodwill value of its Kraft and Oscar Mayer trademarks this year.

Operating margins at Kraft-Heinz have generally fallen since the original post-merger boost, whereas the industry margin has been more or less flat, even amid mounting headwinds. We believe that the company’s troubles stem from its overpromising on cost savings while failing to take into account the need to reinvigorate its once great brands.

Overearning at Kraft-Heinz Co.

Failing to reinvest in its brands has led to falling operating margins at KHC post-merger, whereas the industry margin has been more or less flat.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 9/28/18.

Staying Relevant

Kraft-Heinz is more the exception than the rule, in our view, as many of the once-sleepy giants of the food and beverage industry have come alive to maintain relevance in today’s marketplace, even if it results in short-term pain. Some companies are investing in price (dropping prices to compete with private labels) in order to drum up volume and eventually top-line growth. We are also seeing signs of innovation. Kellogg, for instance, is investing in its supply chain and single-serve packaging formats, given the popularity of on-the-go food offerings. The company admits that the initiative may be a weight on operating margins in the near term, but should ultimately lead to both organic and operating income growth over time.

Investment in the future, however, costs money, and often that has taken the form of debt-fueled shopping sprees by legacy brand owners. A wave of consolidation has washed over the industry. Just last year, companies were willing to increase leverage and risk ratings downgrades in order to diversify business lines away from traditional center aisle goods. Both General Mills and J.M. Smucker, for example, acquired pet food companies. Conagra Brands bought Pinnacle Foods. Campbell Soup purchased Snyder’s Lance. And this trend is not entirely new. Taking note of shifting consumer preferences, General Mills purchased organic food brand Annie’s Homegrown in 2014 for $820 million. In 2017, Kellogg paid $600 million for Chicago Bar Company, the makers of all-natural RXBar protein bars.

Kraft-Heinz, with its dogged focus on margins, has for the most part been caught on the wrong side of this shift. By neglecting brands during a generational industry transition, management lost the margin-enhancing leverage it previously held over retailers – a reality evident in declining profitability. Investors are likely to be tolerant of margin compression if it is being driven by potentially high-return investment, less so when it’s due to loss of relevance and pricing power in the marketplace. Kraft-Heinz’ situation has been exacerbated by both climbing freight costs due to more stringent U.S. trucking regulations and higher labor costs given the tight U.S. job market.

Reconfiguring for Growth

Now that many of these food and beverage giants have engineered a shift toward grocers’ outer aisles, they are divesting lower-growth, lower-margin business lines in order to refocus their core portfolios and reconfigure them for growth. Smucker sold its U.S. baking assets, including the Pillsbury brand, to a private equity firm last year. Others, like Campbell Soup, are seeking to streamline by geography and unload assets domiciled outside of the U.S. General Mills announced plans to divest 5% of its portfolio, and anticipates approximately 1% organic growth as a result. Even Kraft-Heinz hinted at the possibility of asset sales, starting with its Maxwell House coffee brand.

In many respects, the recent activity of Campbell serves as a template of how management teams can shift their strategic focus, using tools such as acquisitions and divestitures, and still look after bondholder interests. Upon recognizing the more attractive growth profile of snacks relative to its core products, Campbell purchased Snyder’s Lance, the maker of Snyder’s pretzels and Kettle Brand chips, in an effort to boost revenues. While this weighed on the company’s bond valuations, Campbell is in the process of selling off a portfolio of non-core brands in order to pay down debt. Investors have subsequently been rewarded as management illustrated its commitment to maintaining the firm’s investment-grade credit rating.

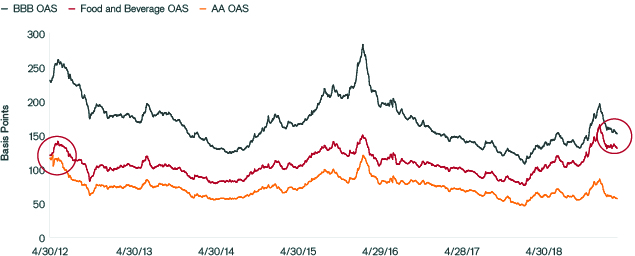

Investment-Grade Food and Beverage Spreads

The food and beverage sector has traded down from AA-like valuations to be more in line with BBB’s, reflecting the plethora of challenges the industry is facing.

Notes: Bond ratings are measured on a scale that generally ranges from AAA (highest) to D (lowest). Option-Adjusted Spread (OAS) measures the spread between a fixed-income security rate and the risk-free rate of return, which is adjusted to take into account an embedded option. 100 basis points equals 1%.

Bad Stocks ≠ Bad Bonds

Margin improvement remains an important metric for investors to watch, but it may temporarily take a backseat for management teams as industry behemoths scramble to breathe life back into legacy brands. This is a tilt that may be less attractive for equity investors, especially given that the divestiture of assets could mean equity multiples will be forever lower.

From a bond perspective, however, the industry looks more attractive than it has in some time. Since coming out of the Global Financial Crisis, the sector has traded down from AA-like valuations to be more in line with BBB’s, and has consistently underperformed its peers in the investment-grade index. The extensive revaluation suggests that the industry’s headwinds are well acknowledged, and appropriately reflected in valuations. Further, the majority of these companies have made potentially transformative acquisitions, and investment into their brands, creating a visible path to growth.

In a relatively rare occurrence for investment-grade industries, nearly the entire industry is planning to pay down debt, and non-core divestitures are providing the cash to do it. A willingness to hold dividends steady, or to cut them, in the case of Kraft-Heinz, is an additional proof point to the industry’s commitment to investment-grade ratings and prudent capital structures.

As these companies look to delever, active managers can benefit from analyzing the capital structure to determine which bonds are ripe for pay down.

Wise Investors will Shop Around

While earnings may not be off to the races, in the event of a downturn, the steady cash flow of these consumer staples should be protected. That is not to say, however, that every company looks attractive. It’s those that are investing in innovation and brand renovation that are going to be better off in the days ahead. Those that have relied on their everyday brands and cost-cutting their way to prosperity still have some work to do. Further, we expect the trend of industry consolidation to continue, making it imperative for investors to watch those names that have not yet utilized their balance sheets for signs of potential merger and acquisition activity.

Global Fixed Income Compass

Explore MoreMore from Our Investment Professionals

How Did They Miss it? Central Bankers and the Global Economic DownturnJenna Barnard, Co-Head of Strategic Fixed Income, explains how and why so many major central banks have been wrong-footed on economic growth in their countries and around the globe. Have We Returned to a Goldilocks Economy?

Jim Cielinski, Global Head of Fixed Income, provides his perspective on some of the key macroeconomic factors that are driving fixed income markets. China: The Swing Factor in Global Growth

Jennifer James, Lead Analyst within the Emerging Market Debt team, looks at the importance of China for Global growth and how policy shifts may be opening up domestic opportunities.