Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

Tom Ross, corporate credit portfolio manager, looks at the idiosyncrasies of the European high yield bond market, one of the last bastions of income in a yield-starved world.

‘It is better to have a permanent income than be fascinating’, claimed the celebrated novelist and playwright Oscar Wilde. As bond investors who are often unjustly characterised for being dull and conservative by our equity cousins, we might take umbrage with the latter part of this quote but would wholeheartedly support the premise of a reliable income.

For investors in Europe, trying to achieve an attractive income has become increasingly challenging. Expectations that the European Central Bank (ECB) would follow the US Federal Reserve and raise interest rates have been dashed. In part, by the US Federal Reserve itself, whose dovish pivot away from further tightening has taken the pressure off other central banks. For the most part, however, central banks are responding to the general economic slowdown, hesitant to tighten further for fear of choking off economic growth.

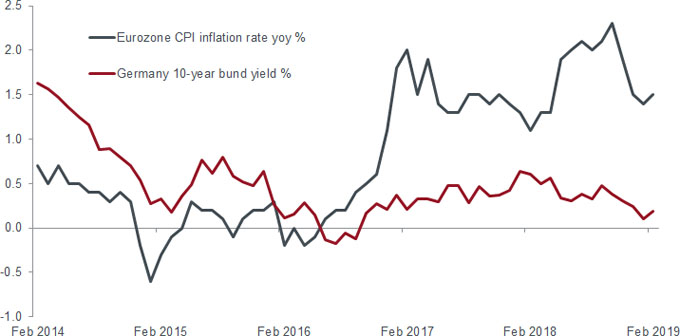

For now, the expectation is that the key monetary policy interest rate in the eurozone will remain at zero, the level it has occupied since March 2016. In fact, at its policy meeting in March 2019, the ECB stated that interest rates would remain at current levels to the end of the year. In the absence of higher inflation or an economic growth spurt this is likely to anchor government bond yields at low levels. For investors looking for income this leaves scant pickings at the safest end of the credit spectrum: the yield on a short-dated 3-month German bund was in negative territory in early March, with even the 10-year German bund offering less than 0.1%1. With inflation in the Eurozone running at 1.5% in the year to February 2019, investors in bunds are essentially accepting a reduction in their real-term spending power in return for the backing of the German government.

[caption id=”attachment_158010″ align=”alignnone” width=”680″] Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, 28 February 2014 to 28 February 2019, Eurozone CPI, Datastream benchmark 10-year German government bond redemption yield. 1Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, at 7 March 2019, Datastream benchmark 10-year German government bond redemption yield. Yields may vary and are not guaranteed.[/caption]

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, 28 February 2014 to 28 February 2019, Eurozone CPI, Datastream benchmark 10-year German government bond redemption yield. 1Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, at 7 March 2019, Datastream benchmark 10-year German government bond redemption yield. Yields may vary and are not guaranteed.[/caption]

Moving further along the credit spectrum to investment grade corporate bonds – debt issued by a company with a AAA+ to BBB- credit rating – offers more in the way of income. The ICE BofAML Euro Corporate Index yields 1.0%2. Yet it is sub-investment grade bonds – high yield – where the yield truly becomes fascinating, with the ICE BofAML European Currency High Yield Index yielding 4.1%2.

2Source: Bloomberg, at 7 March 2019. Yields may vary and are not guaranteed

Within this yield figure is a premium for risk – the very real risk that a company could default and fail to meet its obligations either in terms of payment of coupon (regular interest payments) or repayment of par to investors. High yield defaults in Europe have been low – just 0.9% on a 12-month trailing basis to February 2019 according to Moody’s the credit rating agency. The default rate is expected to climb but remain below the historical 15-year average of 2.7% in the coming 12 months as refinancing remains accessible and the rates companies have to pay remain low.

Borrowing companies should be able to find willing investors in their debt so long as the economic outlook does not deteriorate too much. Given the idiosyncratic risk among high yield borrowers it is therefore worth looking closely at corporate fundamentals. High yield as a classification covers a wide spectrum of debt-issuing companies in various states of creditworthiness. There is a big difference between a high yield bond rated lower down the ratings spectrum at B- and one with the highest quality high yield rating of BB+. For example, credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s compiled data on high yield European bonds between 1981 and 2017, which showed that over a five-year time horizon a cumulative 23.99% of the B- rated bonds defaulted, compared with just 0.56% of BB+ rated bonds. There is clearly a trade-off between capturing a higher yield and assuming more default risk.

More important perhaps than the credit rating is the direction of travel. A company rated BB- but with improving fundamentals is potentially more attractive than a company rated BB+ but with a deteriorating outlook. This is especially true in an age where disruption can rapidly undermine the business model and cash flow of a company. Recent defaults are symptomatic of this changing world: for example, Astaldi, an Italian construction company, was a victim of economic weakness in Italy that made its debt servicing costs too onerous while political turmoil in Turkey hampered its efforts to raise cash from asset sales; or Johnston Press, a UK regional newspaper publisher, which has seen the trend to online media consumption and a shift to digital advertising hollow out its revenues.

In the other direction are companies that are benefiting from improving circumstances or self-help measures. Such companies are likely to see their bond prices rise or remain stable as investors have greater confidence in income payments being met. In the UK, Tesco, the supermarket group, has worked to reduce its net debt and compete with discount supermarkets. It has already gained one investment grade rating from rating agency Fitch and may be on the cusp of receiving full investment grade status if one of the other two rating agencies follows suit. Companies that fully moved to investment grade status in 2018 included Stora Enso, the Finnish pulp and paper group, and ArcelorMittal, the global steel company headquartered in Luxembourg.

It might be assumed that the macroeconomic backdrop dictates when companies are downgraded from investment grade to high yield (fallen angels) and when they are upgraded from high yield to investment grade (rising stars), yet the reality is more nuanced. Often there is a time lag between the economy deteriorating and companies getting into difficulty – there were few fallen angels in 2008-09 – yet plenty in 2015/16 when the rapid oil price decline caused a broad sector de-rating. We did say high yield was fascinating.

Bund: German government bond

Yield: The income that a bond pays as a percentage of its bond price. A bond paying €3 per annum with a price of €100 would have a yield of 3%.

ICE BofAML: Intercontinental Exchange (ICE Data Services) acquired Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s fixed income index business and renamed these indices ICE BofAML.

Credit ratings: A score assigned to a borrower, based on their creditworthiness. It may apply to a government or company, or to one of their individual debts or financial obligations. An entity issuing investment-grade bonds would typically have a higher credit rating than one issuing high-yield bonds. The rating is usually given by credit rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor’s or Fitch, which use standardised scores such as ‘AAA’ (a high credit rating) or ‘B-’ (a low credit rating). Moody’s, another well known credit rating agency, uses a slightly different format with Aaa (a high credit rating) and B3 (a low credit rating) as per the table below. The ratings spectrum starts at the top with AAA (highest quality) and progresses down the alphabet to C and D, which indicate a borrower that is vulnerable to defaulting or has defaulted.