It is a simple fact that society cannot go cold turkey on hydrocarbons, as much as the more extreme ends of the green lobby would like to believe. While we agree with the sentiment behind ‘Stop Oil’, any attempt to do this must happen in an orderly fashion that takes society with it. Such a journey will take time. The oil & gas industry has in place the infrastructure, technology, cash flow and ability to fund new investment, which makes the industry essential for change to happen.

Big oil sets ambitious climate targets

In recent years big oil has aggressively pivoted to align corporate strategy to a net zero world, setting increasingly ambitious emissions targets; yet as recently as 2019, none of the three largest European oil majors had set a 2030 emissions target. We should note, however, that these targets are not set in stone. Rather, they are likely to shift as the realities of achieving an ‘orderly’ transition sets in. This was most recently the case in February when BP moderated its climate targets to meet immediate energy requirements in response to limited supply from Russia. It would not surprise us to see other oil majors scale up and down the intensity of their climate targets as required. Disclosure and consistency (different base years for example) will also remain a challenge for comparing ambitions. Regardless, the direction for oil companies is clear.

Oil & gas companies environmental targets tend to come in two forms:

- absolute carbon emissions targets (in MtCO2e) using Scope 1, 2 &/or 3; and

- carbon intensity targets of products (in gCO2e/MJ) which considers the company’s absolute carbon emissions emitted per MJ of energy provided from its defined products.

Scope 1 emissions are generated directly through a company’s own operations. For oil firms, the main ways to reduce these emissions involve reducing flaring (capturing excess gas rather than burning it or simply managing the oil field more efficiently) and exiting from carbon-intensive projects. Scope 2 emissions include those indirectly produced from power consumption. In this case, many oil companies are using electricity provided from low carbon sources, fuel switching, recycling heat and increasing energy efficiency.

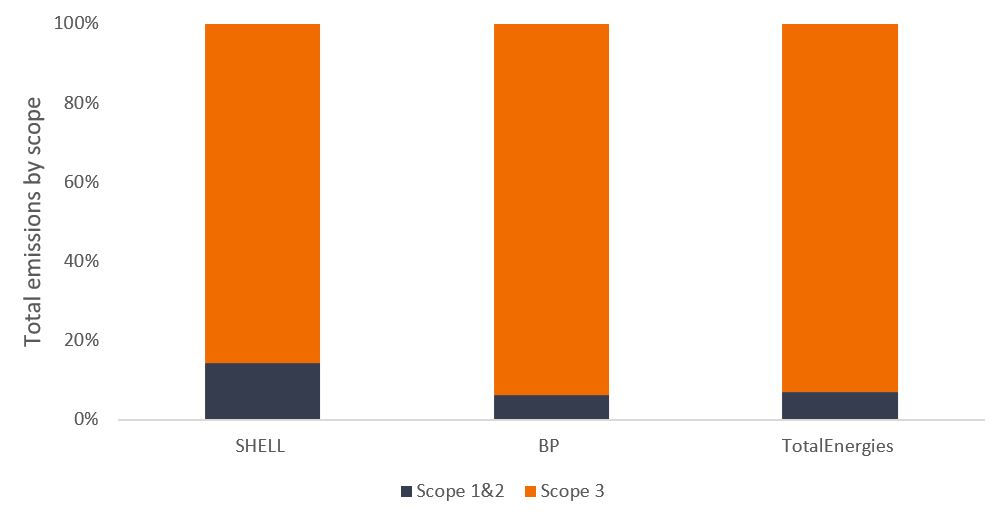

Focusing on emissions reduction from the companies’ own operations is usually considered the easiest win and it is therefore these first two scopes that we have seen the most aggressive targets. By 2030, Shell and BP have targeted a 50% reduction in scope 1 and 2 emissions, and TotalEnergies a 40% reduction.1 However, while these emission reductions should be material by 2030, they are somewhat limited and comprise a relatively small portion of overall emissions– chart 1.

Scope 3 emissions are those associated with the consumption of products sold. These represent the vast majority of ‘well to wheel’ emissions and are those where a longer transition is required. By their nature, scope 3 reduction targets are more difficult to control and therefore make up a much smaller portion of overall reduction targets.

Chart 1: Scope 3 emissions versus scope 1 & 2 for big oil

Source: MSCI, Janus Henderson, as at 30 December 2022. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

As is the case for many sectors, the method to calculate scope 3 emissions is not consistent across the oil & gas industry. Regardless of the exact methodology, we know that scope 3 represents a significant portion of emissions and is therefore key to long term decarbonisation.

The driver of scope 3 emission reductions lies in the company’s sales and production mix. The main ways for oil companies to reduce scope 3 emissions include:

- shifting production from oil to gas (liquified natural gas releases approximately 20-25% less emissions than traditional fossil fuels)

- expanding downstream integration in gas (with production refining, retail marketing and power supplied from gas)

- increasing sales of biofuels and carbon capture

- natural sinks to reduce net emissions

- replacing fossil fuel sales with renewables

Renewables roll out

The scale and commitment of energy companies to increase solar and wind in their production mix often gets overlooked due to its low base versus traditional fuels. However, in absolute terms the shifts are far more dramatic.

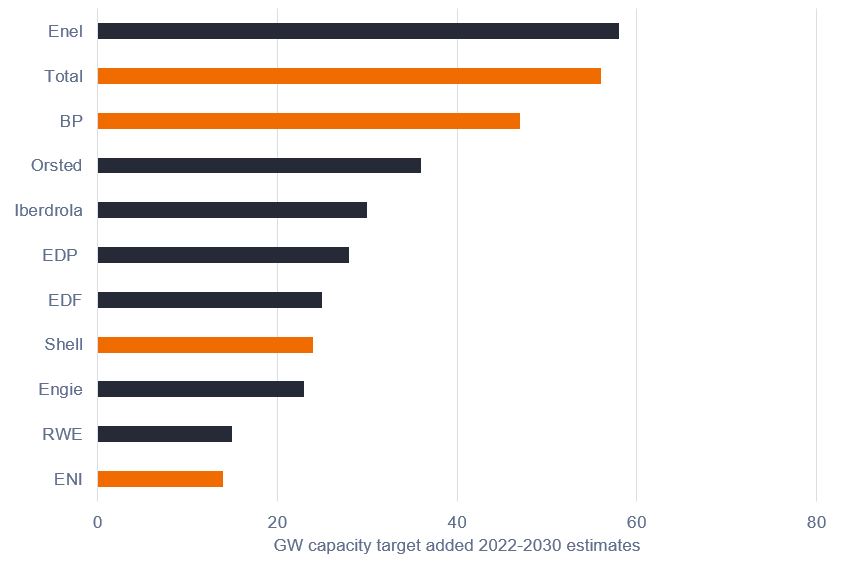

In 2022, Shell, Total Energies and BP had a combined low-carbon capital expenditure (capex) in the region of $9bn, and these numbers are set to grow, with targets of 20-50% capex by 2025/2030.2 This expenditure translates to the oil majors having some of the largest renewable energy growth plans in Europe; chart 2 shows big oil growth plans compared to the incumbent developers, utilities.

Chart 2: European players have big growth plans

Source: MSCI, Janus Henderson, Exane BNP Research, Credit Suisse Research, as at 30 December 2022. Orange bars indicate oil company; black bars indicate utilities company. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

In addition, these companies have become disciplined when it comes to exploring/extracting for new oil projects which will see the percentage of renewables increase in the mix even further. To supplement this renewable-led electrification of our energy supply we are also seeing companies with large retail networks committing to charging point roll outs – Shell targets 2.5m by 2030 aiding the demand side of the equation as well as the supply side.3

Solutions for hard-to-abate sectors

While electrification is often touted as the main solution to reduce dependence on hydrocarbons, the energy density of electricity is far less than hydrocarbons which could prove troublesome in some instances. Currently, the battery size required for a plane to reach take-off speed would hinder the ability to take off at all. Other hard-to-abate sectors alongside aviation include steel, shipping, cement and similar chemical processes. The solutions, some of which are noted below, also look likely to heavily involve the oil majors.

- Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) involves the capture of CO2 from large point sources that release emissions – such as power generation, oil wells or industrial facilities – and has been used by energy companies for many years to reduce their own emissions. CCUS can also capture CO2 directly from the atmosphere. If not utilised on-site, captured CO2 is compressed and transported to be used in a range of applications or injected into deep geological formations which trap the CO2 for permanent storage. Until recently, this process was considered a cost of doing business. Many oil majors are now looking to increase their CCUS capabilities to start selling the service externally by charging per tonne of CO2 captured for external carbon emitters. Given their history in this area, oil companies are uniquely positioned for this opportunity.

- Biofuels are created using an organic material (‘feedstock’), typically blended with traditional diesel/aviation fuel. While these fuels still release emissions on combustion, they are considered sustainable because of the carbon captured during the growth of the organic material. Although biofuels might not be the ultimate solution, they could certainly be part of the transition, especially as the primary feedstocks (sugar-starch crops and oils from rapeseed or palm oil) can put the process at odds with food security. Other feedstocks being explored include agricultural waste (cow manure) and sea algae. Both European pulp and paper company UPM and Neste have been pioneering technology in this area, but it is also a significant element of the oil majors transition strategies.

- Hydrogen could be considered the ultimate solution. Green hydrogen (produced using purely renewable energy and electrolysis) has no emissions at point of use and can be stored for long periods and transported large distances compared to electricity. The main problem is that much of the existing property, plant, equipment and devices for hydrogen production are currently running on fossil fuels and will need to be completely replaced. Again, oil companies’ experience in the operation of upstream and midstream infrastructure necessary to deliver a gas to market will be vital in this transition.

For us, how these processes can interact in tandem is where the scale of the oil majors shows their benefit. Through their trading businesses, oil firms could be a one-stop shop for a company’s energy needs – working with them to reach the best combination to meet their specific energy needs.

Conclusion

The complexity of the carbon chain in society means that the transition to lower carbon solutions cannot happen overnight. The good news is that the technology is either ready (the cost of wind and solar is competitive with traditional fuels) or fast approaching (hydrogen and biofuels). Oil majors are committing huge amounts of capital to aide this shift, thus far in a way that largely aligns all stakeholders. Ultimately, these companies are fast moving from being major oil companies to integrated energy companies with whom the energy transition is totally reliant. We prefer those names that exhibit strong capital discipline whilst showing a strong commitment to a transformational shift within their businesses.

Net zero: refers to the balance between the amount of greenhouse gas produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. Net zero is reached when the amount of greenhouse gas added is no more than the amount taken away.

1 Comparable base year targets: Shell = 2016; BP = 2019; TotalEnergies = 2015. Reduction targets sourced from individual company reports.

2 MSCI, Janus Henderson, Exane BNP Research, Credit Suisse Research, as at 30 December 2022.

3 Shell, “Shell UK aims for 90% of drivers to be within 210 minutes’ drive of a shell rapid charger by 2030”, 11 May 2022.

References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- Shares/Units can lose value rapidly, and typically involve higher risks than bonds or money market instruments. The value of your investment may fall as a result.

- Shares of small and mid-size companies can be more volatile than shares of larger companies, and at times it may be difficult to value or to sell shares at desired times and prices, increasing the risk of losses.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives with the aim of reducing risk or managing the portfolio more efficiently. However this introduces other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.