| The JH Explorer series follows our investment teams across the globe and shares their on-the-ground research at a country and company level. |

Recently we visited Kai Tak in Hong Kong, an area probably more famous as the site of Hong Kong’s original airport famed for its ‘Checkerboard Hill turn’, to line up with runway (a 47-degree maneuver at low altitude to avoid dense urban areas and mountainous terrain), than the mixed-use development it has become today. Kai Tak itself was originally the vision of two men, Ho Kai and Au Tak, who built it from reclaimed land in the 1920s with the plan to deliver a residential development for wealthy immigrants. Unfortunately, when that plan failed, the land was acquired by the government, which then turned it into an airfield.

Kai Tak today

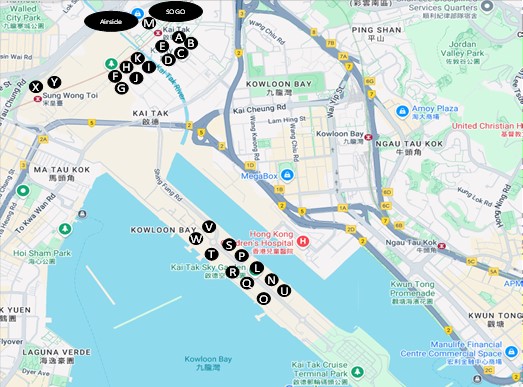

A century later, Kai Tak has finally become what it was originally intended for – a mixed-use development scheme with, at its centrepiece, a new 50,000-seat stadium, known as Kai Tak Sports Park (which will open soon and host a Coldplay concert). Another key component has been the residential developments, which have been built close to the Kai Tak MTR (Mass Transit Railway) station over the last few years, and more recently, the new developments that have been built on the runway itself – these have been more difficult to sell.

Hong Kong residential is struggling

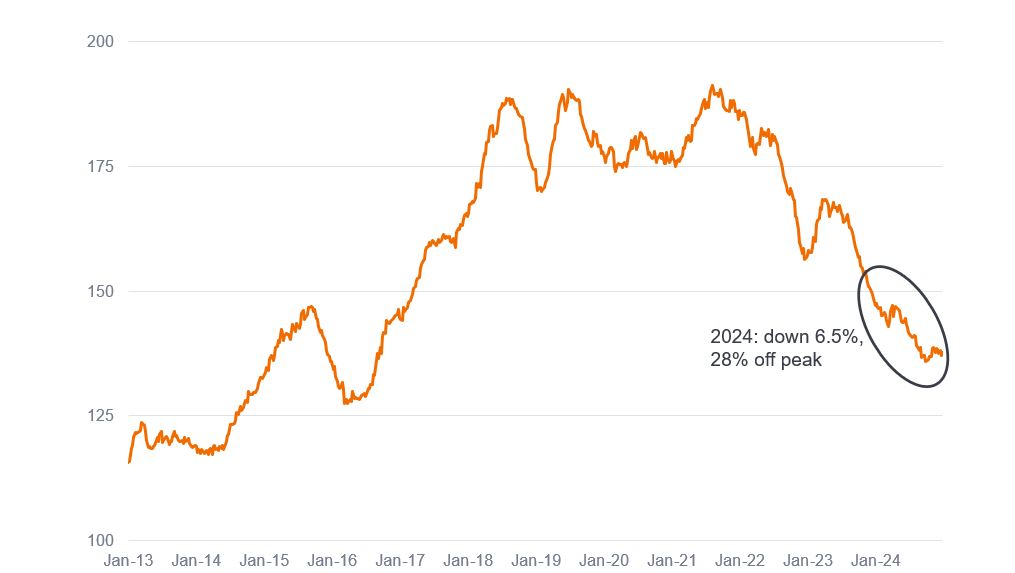

Kai Tak’s situation is not surprising given the state of the Hong Kong residential market, which has been in free fall for the last four years, with values down some 28% since the peak in August 2021.

Figure 1: Residential sector weakness continues

Source: Centaline, BoFA Global Research. Weekly data from 6 January 2013 – 24 December 2024.

The residential malaise can be attributed to several negative factors, such as poor affordability (Hong Kong ranked as the least affordable city in 2023),1 rising interest rates (through the US$/HK$ currency peg), and a changing political environment.

Kai Tak is almost the perfect depiction of Hong Kong’s ‘boom and bust’ residential market over the past decade. The first land sale here in 2013 at HK$5,157 per square foot (psf) climbed steadily to the peak of almost HK$20,000 psf in 2019 in a flurry of land grab deals. It has now gone full circle with a plot on the runway sold in 2023 back at around HK$5,400 psf.

‘The Knightsbridge’ – a seafront view for a mere US$5m

One of the projects we visited on the more ‘glamourous’ west-facing side of the runway with views over Kowloon Bay towards Victoria Harbour was The Knightsbridge. We noted more sales staff than tenants. Buyers are struggling with the high interest rate environment and still high average prices of more than HK$30,000 psf, translating into circa US$5 million for a 1,380 sqft apartment. Still, the view was spectacular!

A luxury ‘The Knightsbridge’ apartment unit

Soft demand is clearly an issue, but that is not the only thing keeping buyers away. Supply levels remain elevated. Hong Kong’s overall unsold residential inventory is running at record highs of more than 50,000 units, with Kai Tak accounting for a quarter of this. 26,000 units have been built in Kai Tak over the last number of years, with almost 60% sitting on the runway, of which only about 2,000 have been sold.

Q – location of The Knightsbridge development, “a luxury urban landmark, a world-class mansion on the waterfront”.

Paradise lost?

But what does this mean for the developers who built these units? Almost all of the major Hong Kong property developers and a few Chinese developers have exposure in the Kai Tak project. With supply this high and demand this low, margins (even at these elevated price levels) are thin, if at all positive.

For some companies with better balance sheets, they may be able to ride this downturn out, however, others may not be so lucky, with cracks already beginning to appear. We have seen a couple of distressed developers offload their undeveloped plots at a significant loss. Many others have also taken steep write-downs on their exposure in the area. Several developers with cash flow issues have chosen to cut prices even if it means a loss, just to move inventory. The potential fallout from any stress, given the large level of unsold inventory, will no doubt have a knock-on impact, potentially even on stronger blue-chip companies.

While Mr Kai and Mr Tak’s goal to build a garden state from reclaimed land here may finally have been realised a hundred years later, whether their vision for it has also been realised, remains unclear.

1 Demographia International Housing Affordability Report.

Balance sheet: a financial statement summarising a company’s assets, liabilities and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time. Balance sheet strength is an indicator of a company’s financial health and stability.

Blue chip companies: widely known, well-established, and financially stable companies, typically with a long record of reliable and stable growth.

Cash flow issues: occurs when the total amount of money flowing into the business is less than money going out. Often caused by poor cash management, it may impact a company in terms of repaying debt and other expenses, and ultimately could lead to business closure.

Currency peg: a monetary control policy where a government or central bank sets a fixed exchange rate between their domestic currency and a foreign currency.