Subscribe

Sign up for timely perspectives delivered to your inbox.

The money illusion theory states that people tend to think about their wealth in nominal terms instead of real terms, leading them to erroneously believe the value of their dollars is constant. Wealth Strategist Ben Rizzuto explains how to help clients avoid this common cognitive bias.

A recent article by Jeff Sommer in the New York Times reminded me of one of my favorite economic theories/cognitive biases.1 The theory is called money illusion, and it was developed by John Maynard Keyes in the early twentieth century and further popularized by Irving Fisher in his book “The Money Illusion,” published in 1928. While the theory may be obscure to many, money illusion is something investors experience every day – especially during periods of high inflation.

We’ve all heard plenty about inflation on the news, but many investors don’t fully understand why prices have increased. And the truth is, they may not even care; they just know that when they go to the gas station or the supermarket, they’re spending more than they were in the past.

While there are all sorts of underlying economic factors that affect a country’s inflation levels, the result is that people are losing money. And what happens when investors experience loss? They react emotionally. Not only that, but they feel the sting of those losses far more than the pleasure of gains. This leads investors to make long-term financial decisions based on short-term emotions.

Consider the person who, when the price of filling up her car with gas hits triple digits, goes from thinking about buying a Tesla to buying a Tesla.

If that’s an (admittedly somewhat dramatic) irrational reaction, how would a rational investor react to inflation? They would invest in assets that are likely to grow at a rate higher than that of inflation, such as equities, commodities, or real estate. On the other hand, the irrational investor does just the opposite: They take their chips off the table. They divest their “risky” assets and put more of those assets in cash. And this, dear reader, is where money illusion comes into play.

In his book, Fisher described money illusion’s effect on a German shopkeeper during a time in the late 1920s when Germany’s currency, the mark at that time, was undergoing massive devaluation due to hyperinflation.

The shopkeeper believed that because she was selling shirts above the cost she acquired them for, she was making a profit. However, according to Fisher, the shopkeeper lost money on a net basis because inflationary pressures had eroded her purchasing power. Fisher concluded that people think about their wealth in nominal terms, not in real terms, which provides a false sense of security of an individual’s wealth. Put more simply, people erroneously believe the value of their marks – or euros or dollars – is constant.

This idea was further explored more recently by Fabio Braggion from Tilburg University. In his research, Braggion analyzed German buy and sell activity in stocks and bonds during that period of 1920s hyperinflation. What he found was that a 1% increase in inflation led to a 3% decrease in stock balances.2 Based on this research, we see that, due to money illusion, investors can and do act irrationally during periods of inflation.

Even though your clients are certainly not Germans living in the 1920s, we continue to see investors around the world making irrational decisions as inflation increases. In fact, inflation or the fear of inflation can drive investors to do arguably one of the worst things for their portfolios – hold on to cash.

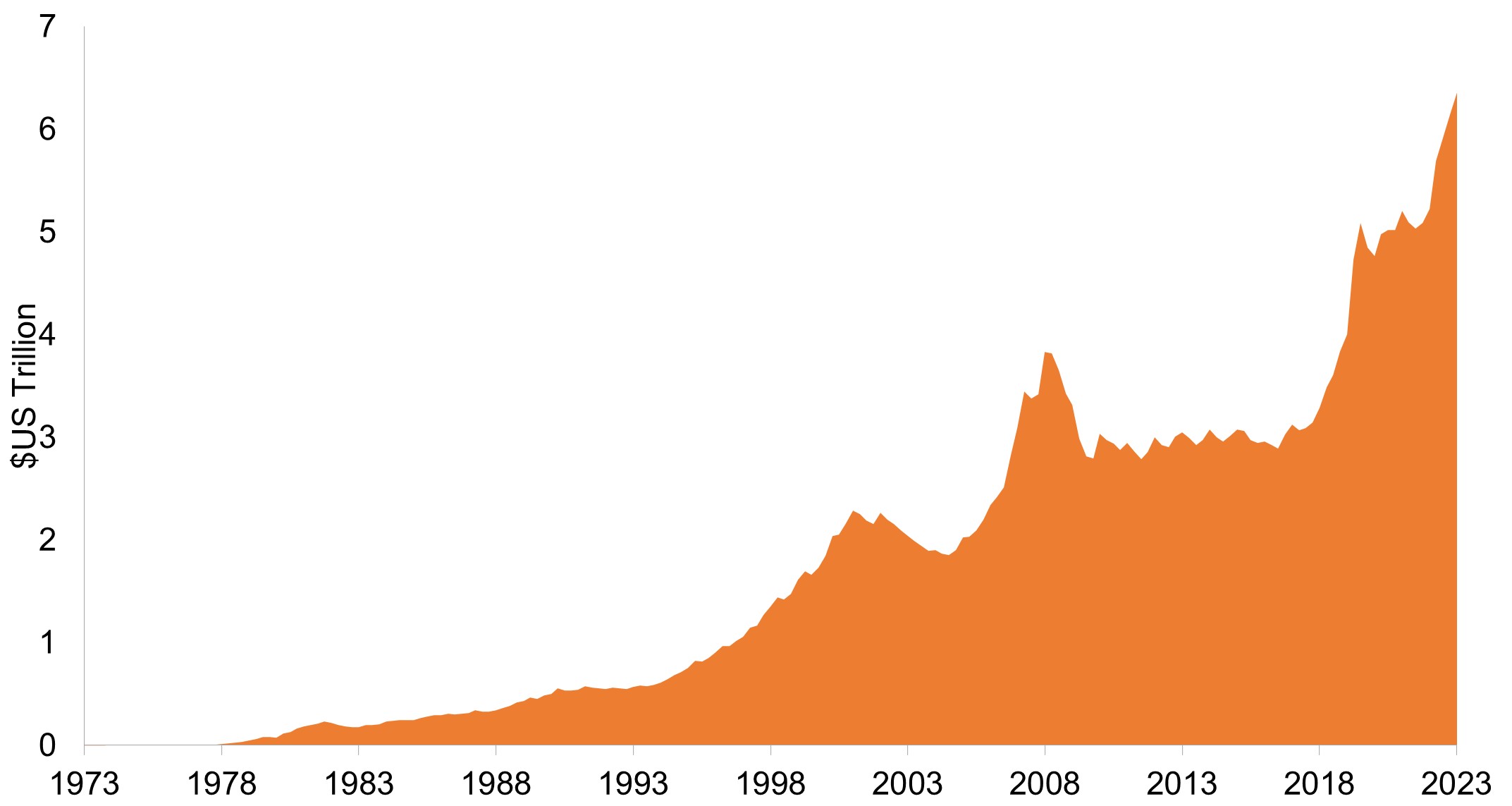

The chart below illustrates the growth of money market holdings for U.S. investors since 1973. Notably, it shows how their growth has surged since 2020.

Source: Federal Reserve, as of 31 December 2023. Note: 60/40 portfolio based on 60% S&P 500 Index and 40% Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index through 31 March 2024; money market returns based on average returns of a pool of U.S. money market returns through 31 March 2024.

Of course, interest rates have also increased since 2020, which has led to annual money market yields of approximately 5%. Investors obviously enjoy the yield and safety provided by these investments, but are they missing out?

Annual inflation was 3.5% in March 2024, so in real terms that 5% yield on money markets is closer to 1.5%. This is additive and much better than the negative real yields investors were getting in 2022. However, just as those German shopkeepers in the 1920s, today’s investors are falling victim to the money illusion as they continue to move assets into money market funds. Along with that, as Sommer noted in his article, the dollars that accumulate in our accounts can steadily lose their purchasing power due to inflation. For example, he noted that a March 2021 dollar was worth only $0.85 today.3

All of this highlights how important it is to educate investors on inflation, nominal and real rates of growth, and how these factors may give them a false sense of security. Furthermore, while investors may enjoy the “nominal” safety of 5% money market yields, it may not serve their long-term goals. For example, during a hypothetical one-year period, a 60/40 portfolio – 60% equities and 40% bonds – would have returned 18.6% (15.1% in real terms). This comparison of course needs to be done within the context of proper asset allocation and risk tolerance assessments, but it may help start the discussion and lay bare the risk of leaving assets in lower-yielding money market funds as financial markets grind higher.

To help clients avoid falling into the money illusion trap, consider talking them through an example that offers a different perspective. For example, ask your client to think of themselves as a business, just like that German shopkeeper Irving Fisher studied back in 1928. To run a profitable business over the long run your sale prices must exceed your production costs, as shown below:

Year 1

-Sale price per shirt = $15

-Production cost per shirt = $10

-Net profit per shirt = $5

Year 2

-Sale price per shirt = $15

-Production cost per shirt = $12

-Net profit per shirt = $3

Your clients can apply this same basic thinking to their personal finances. Instead of shirts, their product is their savings, and the input cost is inflation.

It’s important to note that, in some cases, you may not notice modest inflation from one year to the next. However, the cumulative effect of inflation (along with taxes, etc.) over decades is where it can more noticeably impact wealth accumulation.

Rather than using a generic example, you may want to take a more personal approach by assessing your client’s current asset balance, withdrawal rates, current inflation, and potential future market returns. (Because let’s face it, your clients may have a hard time putting themselves in the shoes of a 1920s German shopkeeper.)

Hopefully these examples help put the concept of money illusion in perspective. But we must remember that sometimes an individual’s emotions can’t be educated away. An investor’s conservative tendencies and irrational response to inflation can lead to a situation where they run out of money much sooner than they may hope.

When this occurs, it’s important to let clients know that they aren’t alone. Explain to them that many people are just as frustrated and concerned with inflation as they are. In fact, 67% of investors in a recent Janus Henderson survey said they were worried about persistent inflation.4 And those concerns lead many people to be conservative, risk averse, and prone to holding their assets in cash. If clients understand that their emotions are shared by others, the hope is that they will say, “OK, if that’s the case, what should I do next?”

Inflation and interest rates may prove to be higher for longer, but taking some time to share the story of a German shopkeeper in 1928 and introducing clients to the concept of money illusion may help them better understand the value of their dollars, how people react during periods of high inflation, and how they can use those lessons to better achieve their financial goals.

1 With Inflation This High, Nobody Knows What a Dollar Is Worth.” New York Times, April 26, 2024.

2 Braggion, Fabbio, von Meyerinck, Felix, Schaub, Nic. “Inflation and Individual Investors’ Behavior: Evidence from the German Hyperinflation.” The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 36, Issue 12. December 2023.

3 “With Inflation This High, Nobody Knows What a Dollar Is Worth.” New York Times, April 26, 2024.

4 Janus Henderson Investor Survey, as of September 2023.