As recently as February, US high yield bonds were yielding on average 7.1%.1 Fast forward to mid-April and US high yield is offering an average yield of 8.5%.1 ‘Liberation Day’ (where the White House announced broad-based tariffs) and subsequent tariff announcements have contributed to a jump in yields of approximately 1.5 percentage points. Consider that you only have to go back to early 2022 and US high yield was yielding 4.4%, almost half what is on offer today.1

Yield is important. It is the compensation investors demand for the risk of lending to a borrower. There is no denying that the policy uncertainty of recent weeks means tail risks (recession, elevated inflation) have risen. Some comfort might be taken from the Trump administration introducing a 90-day pause on tariffs (excluding China) above the baseline tariff of 10% and exclusions for certain goods. This suggests the White House is not blinkered to what happens in financial markets. It does not remove, however, the ongoing concerns that inflation is likely to be higher and growth lower in the US because of higher tariffs.

Given that the tariff picture is still fluid and much of the available economic data is stale, we will leave judgements on the economic outlook for another day. Our purpose in this article is to look dispassionately at the yield on high yield bonds and consider whether an investor might be well served by investing in high yield bonds at current yield levels.

The importance of income

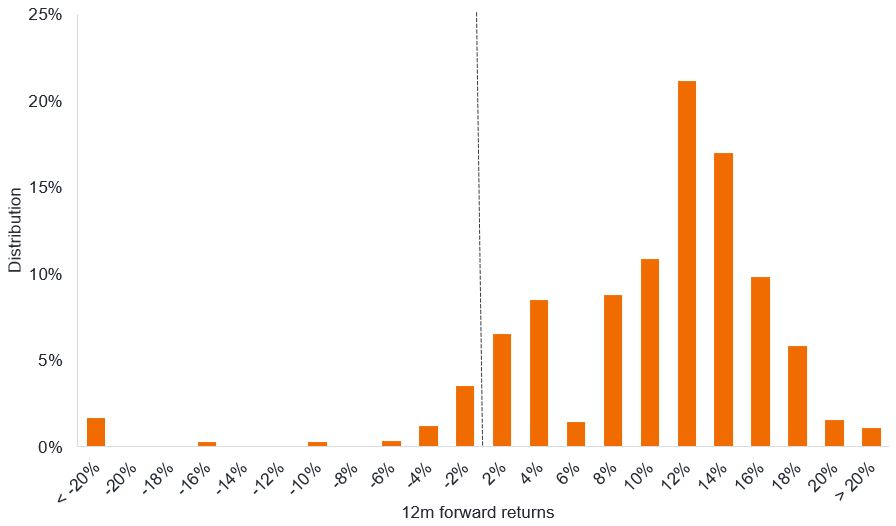

Figure 1 shows the distribution of 12-month forward returns from any day when the starting point of the yield on the US high yield index was between 8% and 9% (i.e. at around current levels). The chart is based on daily data going all the way back to 1994. Investors buying when the yield was between 8% and 9% would only have experienced negative returns 12 months later had they bought in October 1997, August 1998 or between June to November 2007.

Figure 1: Distribution of 12-month forward returns when US HY bonds yield 8% to 9%

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, total returns in US dollars. 12-month forward returns are grouped into return cohorts. Each return cohort covers a two percentage point range (e.g. 2% = 0 to 2%, 4% = 2% to 4%), 25 October 1994 to 11 April 2025. The yield used was the index yield to worst (see definitions). Past performance does not predict future returns.

You will notice that returns are clustered in the positive side of the chart, demarcated by the dotted line. This is not surprising because the average 12-month return when an investor bought the index when it was yielding between 8% and 9% was 8.9% (source as per chart above).

The point here is that it is difficult to achieve a negative outcome from high yield with a high starting yield for several reasons:

One, because a high starting yield means more of the total return is coming from income (a more fixed and predictable element), so you are less reliant on movements in capital (a more volatile element).

Two, a high starting yield means there is probably more likelihood of yields being lower in a year’s time than higher. Think of it a bit like the game show “Card Sharks” or “Play Your Cards Right” where contestants had to guess whether the next card to be revealed from a pack would be higher or lower than the previous card. The higher up the suit the preceding card, the greater the probability the next card would be lower. When yields fall, bond prices rise. Currently, the yield on US high yield sits at the 59th percentile, which means yields have been lower 59% of the time, and higher 41% of the time.2 Again, this is for data going back to 1994, so we are capturing yields beyond the low yield period of the last decade.

Three, recall that the yield on a high yield bond comprises the yield of a government bond of similar maturity PLUS the spread (the additional yield that a high yield bond offers to reflect the credit risk). Treasury yields currently make up around half the yield on the average US high yield bond, so this provides some ballast. If the US economy does deteriorate, raising credit risk for corporates, this might be offset somewhat by US Treasury yields declining. In such an environment, what would probably happen is that spreads on high yield bonds would widen, so the yield on high yield bonds might remain fairly steady.

Another point is that asset allocators are familiar with the arguments above. It drives flows into the asset class when yields reach higher levels, which supports spreads.

Absorbing risks

But what about defaults – the risk that a bondholder fails to meet debt repayments? The US high yield trailing 12-month default rate was just 1.3% at 31 March 2025.3 This is very low but reflects the fact that the high yield bond market has risen in quality over the past couple of decades. Moreover, the COVID shock meant many companies have already gone through a process of strengthening their finances. That said, a sharp weakening in the economy or prolonged high yields (making refinancing more expensive) could see credit metrics deteriorate.

Part of the yield on a high yield bond is made up of the credit spread. This is the portion of the yield above the yield on the US Treasury. The credit spread needs to more than compensate for defaults otherwise there would be little point in taking on the risk of holding high yield corporate bonds. Going back in history, investors in high yield have typically enjoyed what is known as ‘excess spread’ (this is spread above and beyond what was necessary to compensate for default risk).

We can calculate the historical excess spread over time using actual credit spreads, default rates and recovery rates. The recovery rate is the percentage of the par value of the bond that investors expect to recover if the bond defaults (typically this ranges between 20-60%). We adjust the default rate to reflect the fact that some losses are recovered. The formula is:

Credit spread – (subsequent 12m default rate x (100% – Recovery rate)) = Excess spread

For example, plugging in the credit spread of 458 basis points for 31 March 2023, the trailing 12-month default rate a year later on 31 March 2024 was 2.2% (or 220 basis points) with a recovery rate of 40%, we get the following excess spread:

458 – (220 x (100% – 40%)) = 458 – (220 x 0.6) = 458 – 132 = 326 basis points

So an investor who invested in US high yield bonds on 31 March 2023 was rewarded with 326 basis points of excess spread (it was actually closer to 327 basis points but we avoided using too many decimal places in the above example). In mid-April 2025 the credit spread on the US high yield market was 426 basis points4, so theoretically it could absorb a default rate of 4.2% with no recovery and investors would be no worse off than investing in US Treasuries (all else being equal).

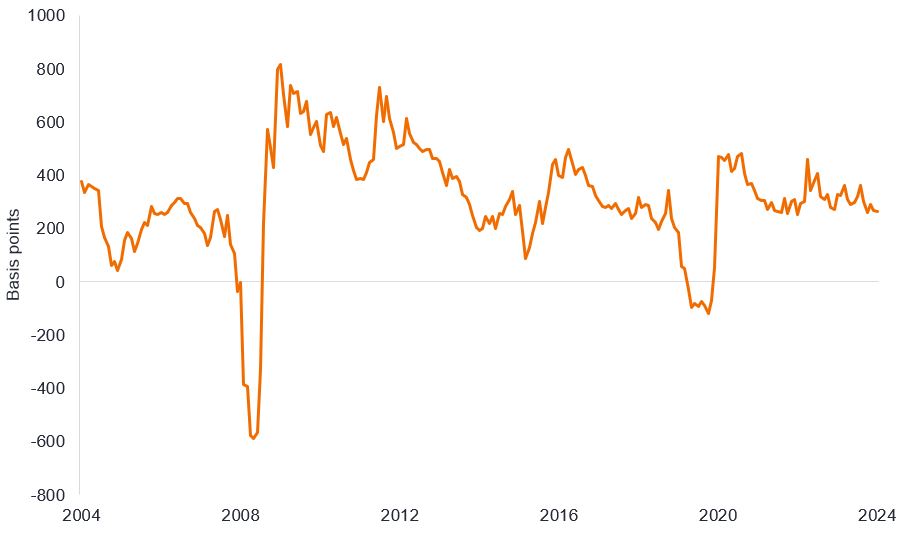

Over the last 20 years there were only two periods where US high yield spreads failed to cover defaults (the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID pandemic). The market quickly recovered however, and over time investors have been more than compensated for actual defaults as shown by the excess spreads in Figure 2.

Figure 2: US high yield excess spreads

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, Bank of America, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, Govt OAS, US high yield trailing 12-month default rate (par weighted), US high yield recovery rate, monthly datapoints, 31 March 2004 to 31 March 2024, using data up to 31 March 2025. Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%. Past performance does not predict future returns.

We will be the first to remind readers that they should not rely on past performance as a guide to future returns. We are also mindful that markets can overshoot in times of stress. It is perfectly possible that yields could rise further from here if investors become more concerned about corporate conditions. We do not yet know the outcome of the tariff negotiations or how consumers and businesses will react to the tariffs. That is why we are keeping a keen eye on the economic data coming out as well as what companies are saying in terms of forward guidance during the earnings reporting season.

What we can surmise from history, however, is that the outcomes for high yield bond investors are typically better when starting yields are high. We recognise that having the courage and patience to sit out volatility can be difficult, but those investors prepared to accept risk are often rewarded.

1Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, yield to worst, (27 February 2025, 11 April 2025, 1 January 2022). Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

2Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, yield to worst, yield at 11 April 2025, percentile rank for period 25 October 1994 to 11 April 2025. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

3Source: Bank of America, 12-month trailing default rate for US high yield, par weighted, at 31 March 2025.

4Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, credit spread (Govt OAS) at 11 April 2025. Spreads may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

The ICE BofA US High Yield Index tracks US dollar denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Credit metrics: A set of financial ratios such as debt levels versus assets or interest payments as a proportion of earnings that help lenders determine a borrower’s ability to repay debt.

Credit rating: An independent assessment of the creditworthiness of a borrower by a recognised agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s or Fitch. Standardised scores such as ‘AAA’ (a high credit rating) or ‘B’ (a low credit rating) are used, although other agencies may present their ratings in different formats. BB is a high yield rating.

Credit spread: The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

High yield bond: Also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy.

Investment grade bond: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments, reflected in the higher rating given to them by credit ratings agencies.

Issuance: The act of making bonds available to investors by the borrowing (issuing) company, typically through a sale of bonds to the public or financial institutions.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Recovery rate: The amount expressed as a percentage, recovered from a loan when the borrower is unable to settle the full outstanding amount.

Refinancing: The process of revising and replacing the terms of an existing borrowing agreement, including replacing debt with new borrowing before or at the time of the debt maturity.

Tail risk: Tail risk events are those that have a small probability of occurring, but which could have a significant effect on performance were they to arise.

Tariff: A duty or tax imposed on goods entering a country.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Yield to worst: The lowest yield a bond with a special feature (such as a call option) can achieve provided the issuer does not default. When used to describe a portfolio, this statistic represents the weighted average across all the underlying bonds held.

Volatility: A measure of risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

Specific risks

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- In addition to income, this share class may distribute realised and unrealised capital gains and original capital invested. Fees, charges and expenses are also deducted from capital. Both factors may result in capital erosion and reduced potential for capital growth. Investors should also note that distributions of this nature may be treated (and taxable) as income depending on local tax legislation.