The Big Exit: Emerging market sovereigns carve a way out of default

A string of successful sovereign restructurings over the past year show that emerging markets debt is approaching a turning point. Portfolio Manager Sorin Pirău from the Emerging Markets Debt Hard Currency Team discusses what this means for investors.

11 minute read

Key takeaways:

• Four frontier markets have recently negotiated their exit from default and have offered investors relatively favourable recovery rates in a positive sign for the emerging markets debt hard currency (EMD HC) asset class.

• New innovative instruments, such as bonds where payouts are contingent on the outcome of various macroeconomic variables, can speed up restructurings and limit investors’ impairment.

• Active investors with a long track record of navigating distressed debt episodes can leverage on their experience and take advantage of mispriced opportunities that emerge throughout the restructuring process.

After a relatively benign period following the global financial crisis (GFC) that only saw a handful of idiosyncratic defaults or restructurings, we saw several emerging market sovereigns falling into debt distress following pandemic-related shocks and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Through a mix of domestic policies, bilateral aid, and multilateral rescues facilitated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), some have made a remarkable comeback, and managed to generate significant returns for bondholders. Pakistan, El Salvador, Egypt and Tunisia are a few examples of countries that managed to avoid default and deliver impressive returns – with hard currency bonds from the likes of Pakistan and El Salvador returning over 170% since the fourth quarter of 20221.

Even for less fortunate countries that were unable to meet obligations on their Eurobond debt, the outcome has not been as grim as first expected. In contrast with corporate credit, when a country goes bankrupt it will not vanish, but instead will continue to operate its core functions and fulfil its obligations to citizens. Hence the sovereign is strongly incentivised to re-establish relations with its creditors to ensure access to private funding, recover from crisis, and ultimately provide for its population. This is a key differentiator for emerging markets debt hard currency (EMD HC) relative to other fixed income asset classes. Thus, not only are default rates lower than in US high yield, recovery rates (the amount creditors recover after a debt default) tend to be higher as well.

JHI

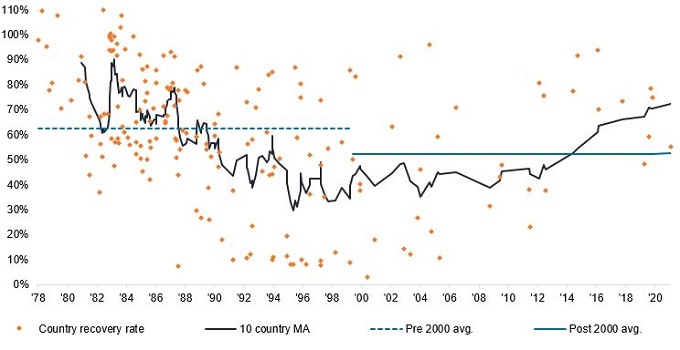

Some of the successful EM sovereign debt restructuring that concluded recently had recovery rates higher than historical averages. According to an analysis done by Morgan Stanley, since 2000 sovereign debt restructurings had on average recovery rates above 50%, with the average of the last 10 completed restructurings reaching as high as 72% (Figure 1). In US high yield, recovery rates are around 46%2.

Figure 1: EM sovereign recovery rates (bond and loans)

Source: Cruces, Juan and Christoph Trebesch (2013): Sovereign Defaults: The Price of Haircuts, American Economic Journal. Updated by Morgan Stanley Research for recent restructurings, as at 8 July 2024.

At the start of 2024, there were eight ongoing sovereign restructuring efforts, cumulatively accounting for just over 3% of the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (JPM EMBI GD) at that time3. The three largest were Ghana, Sri Lanka and Ukraine, each making up roughly 0.7-0.9% of the benchmark, while the others were relatively small.

Figure 2: Sovereign restructuring timelines

Source: Bloomberg, EMTA, Reuters, Barclays Research, as of June-July 2024.

Suriname

The first sovereign borrower to exit default this decade was Suriname, which reached a restructuring agreement with its Eurobond holders in November 2023. This included both a 10-year plain vanilla bond (pays a fixed interest) and an innovative state-contingent debt instrument (SCDI) allowing bondholders to benefit from the upside potential in the country’s oil and gas sector by guaranteeing holders a defined portion of potential oil royalties. Ultimately, investors holding the defaulted bonds received a package valued at more than 100% of the claim as of the end of 2023, marking a remarkable deal for bondholders.

Zambia

The next successful restructuring occurred in June 2024, when Zambia issued two new bonds in exchange for its defaulted maturities: a plain vanilla 2033 maturity and another SCDI maturing in 2053, with financial terms dependent on certain macro thresholds. If these are reached, then the SCDI will deliver accelerated repayments through higher coupons, front-loaded amortisations and a shorter maturity profile.

While bondholders agreed to a 22% nominal haircut – calculated on the entire value of the claim including PDI or past due interest – on the defaulted bonds, the terms of the restructuring were generally favourably perceived, with bonds prices rising to around 76-77 cents on the dollar right before the exchange. The exit yield4 for the plain vanilla bond came just below 10%, rewarding the country for staying on course on its IMF-supported reform programme. A few days after the restructuring settled, the IMF Board approved the third Extended Credit Facility (ECF)5 review and augmented the programme by close to US$400m in response to the ongoing drought in the country.

This was the first successful restructuring achieved under the Common Framework (CF), which consists of a core set of principles – established by the G20 – that were meant to provide a structured and co-ordinated approach for debt treatment, but in the end turned out to be less efficient and far slower than its backers expected, in our view. The hope is that many valuable lessons were learnt by all parties, which should up speed the process for the other two sovereigns negotiating under the CF, namely Ghana and Ethiopia.

In Zambia’s case, bondholders also negotiated the introduction of several non-financial terms, which we see becoming standard practice in other debt restructurings. These were as follows:

- Most Favoured Creditor clause prohibiting other creditors from getting better treatment in net present value (NPV) terms.

- Loss Reinstatement clause allowing creditors to add back to their claim the granted debt relief if Zambia were to default again during the IMF programme.

These clauses in effect allowed bondholders to hedge against future uncertainty and allowed them to proceed with claim reductions without having to wait for these uncertainties to be resolved.

Ghana

These non-financial terms were also included in Ghana’s “Agreement in Principle” (AIP), reached in June 2024 with two bondholder groups, which if accepted will see the country emerge from its 18 month-long default. This restructuring was far less contentious than Zambia’s (which took almost four years to resolve), and it is likely to see bondholders obtain recovery values around the mid-50s, depending on the exit yield. The deal included a 37% haircut for both principal and past due interest and it outlined the conversion of the current Eurobond curve into different types of bonds, some of which are explicitly designed for investors seeking to avoid nominal haircuts on their outstanding claims. Unlike Zambia and Suriname, SCDIs were omitted from the restructuring package, indicating their role as specialised tools rather than universal solutions.

The current deal has already been endorsed by the OCC (Official Creditors Committee, a forum representing the country’s bilateral lenders), which agreed that it fulfils the Comparability of Treatment principle6 – clearing a key hurdle of the Common Framework – and paving the way for the country to launch its debt exchange. A consent solicitation process7 will follow and settlement of the new bonds is expected in early September. Following the agreement, the IMF Board completed the second review of the ECF and disbursed over US$360m to Ghana. In addition to the two non-financial clauses mentioned above, the AIP mandates the government to disclose specific public debt information biannually, a move that significantly enhances transparency.

Sri Lanka

In July 2024, Sri Lanka also announced an AIP with its bondholders, the last major step in the country’s broader debt restructuring process. This followed the finalisation of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the OCC and government approval of the debt agreements made with its bilateral creditors. The deal needs to be approved by the OCC and the IMF, but we expect these steps to be mere formalities.

The terms of the deal were also quite favourable to investors, delivering a package of bonds, in our view, worth around 65 cents on the dollar, depending on exit yield assumptions. Bondholders agreed to take a 28% nominal haircut on over US$12 billion worth of Eurobonds and received instead a package consisting of one conventional plain vanilla bond and four “macro-linked bonds” (MLBs), a type of SCDI. MLBs are a recent innovation, expanding the range of tailor-made debt instruments developed as part of various sovereign debt restructurings.

In the case of Sri Lanka, the coupons and principal of MLBs will be adjusted up or down according to the country’s GDP performance8. Market participants judge this to be an asymmetric upside to recovery values given conservative IMF economic forecasts. Another innovation is the potential introduction of a “Governance-Linked bond”. While details are not yet available, we expect its payouts to be linked to certain reforms to which Sri Lanka committed itself under the IMF programme, like hitting certain tax revenue targets.

The remaining restructurings

Currently there are four other countries that are in various stages of debt restructurings. Lebanon and Venezuela are the ones where prospects appear the most obscured.

Lebanon continues to experience political deadlock, and given the unrest in neighbouring Israel, we believe it is unlikely to embark on a debt restructuring process anytime soon. Its bonds thus trade at some of the most distressed valuations in our investment universe.

While the situation in Venezuela is not much brighter, valuations rose recently after the country’s re-inclusion in EM bond benchmarks following last year’s removal of sanctions on sovereign and quasi-sovereign bonds trading on the secondary market. As this completed in June 2024, the country now makes up around 0.6% of the JPM EMBI GD benchmark9.

In contrast, we expect some progress this year from Ukraine and Ethiopia. In Ukraine’s case, the window of opportunity to reach an agreement is narrowing before the deadline on 1 August, when the debt repayment standstill agreed with private creditors two years ago will expire. The IMF recently published an updated Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA)10 that allowed only “symbolic” (small) cash flows to bondholders during the programme period. The parties involved expressed a strong commitment to find a solution, but thus far their proposals are quite far apart.

In Ethiopia’s case, before it can proceed with creditor negotiations under the Common Framework, the country must satisfy the initial conditions for an IMF programme approval, particularly the liberalisation of its currency market. In the meantime, its sole Eurobond, which is in default, continues to trade above 70 cents on the dollar11, reflecting the market’s expectations of relatively lenient restructuring terms.

An improving risk picture

The four successful sovereign debt restructurings seen over the past year have proven a useful learning opportunity for all parties involved, including creditors, debtors, and officials. Since no two defaults are alike, attempting to use a rigid ‘one size fits all’ template across different restructuring negotiations is often counterproductive. Nevertheless, certain insights can contribute positively to future debt talks. Key among these is the potential for SCDIs to bridge existing gaps between stakeholders when it comes to future macroeconomic assumptions incorporated in the IMF-related Debt Sustainability Analysis. In addition, creditors are becoming more aligned when it comes to defining the debt restructuring perimeter and in assessing adherence to the Comparability of Treatment principle. This should streamline future restructuring efforts, thereby yielding benefits for all parties involved, including investors.

To sum up, it is our view that EMD HC is ready to turn a new leaf, distancing itself from the recent episodes of default that, despite capturing public interest, were not as consequential as suggested, thanks to the diversification of the asset class and the limited size of individual frontier markets within the benchmark. Additionally, with few exceptions, the repercussions of these defaults were significantly milder than feared, demonstrating the robust resilience of the asset class. Finally, being able to invest in distressed sovereign debt also provides rewarding opportunities for active investors that can identify mispriced opportunities amid market turmoil or forced sales of defaulted debt.

Sources

1 Source: Bloomberg, as of 9th July 2024.

2 Source: UBS, 30 June 2024.

3 Source: Macrobond, 1 January 2024.

4 The yield at which the market prices the new bonds once they start trading in the market.

5 ECF provides medium-term financial assistance to low-income countries.

6 The ‘Comparability of Treatment’ assessment requires countries to treat the restructured debt the same as the other debt due to its other external creditors in the scope of the restructuring.

7 A consent solicitation is a process by which a security issuer proposes changes to the material terms of the security agreement.

8 proxied by its average dollar nominal GDP over 2025-2027 subject to a real GDP growth constraint.

9 Source: Macrobond, 28 June 2024.

10 A Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) assesses a country’s capacity to finance its policy objectives and service the ensuing debt without unduly large adjustments, which could otherwise compromise its stability.

11 Source: Bloomberg, as of 9 July 2024.

State contingent debt instrument (SCDI): According to the IMF, these instruments can help better manage public debt in a world of macroeconomic uncertainty. SCDIs link a sovereign’s debt service payments to its capacity to pay, where the latter is linked to real world variables or events. They are applied in cases where disagreements arise between the debtor, creditors, and the IMF regarding essential assumptions in the Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA).

Official Creditors Committee: This group of officials of the country’s bilateral lenders under the G20 Common Framework perform what is called the ‘Comparability of Treatment’ assessment, which requires countries to treat the restructured debt the same as the other debt due to its other external creditors in the scope of the restructuring.

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU): A memorandum of understanding is a type of agreement between two or more parties.

Past due interest (PDI): Interest payments that have not been paid by the due date. Past due interest accumulates from the payment due date until the payment is actually made and is considered part of a bondholder’s total claim in a restructuring process.

Principal: Within fixed income investing, this refers to the original amount loaned to the issuer of a bond. The principal must be returned to the lender at maturity. It is separate from the coupon, which is the regular interest payment.

Coupon: A regular interest payment that is paid on a bond, described as a percentage of the face value of an investment. For example, if a bond has a face value of £100 and a 5% annual coupon, the bond will pay £5 a year in interest.

Amortising: With amortisation, a bond’s principal is divided up and paid off incrementally.

Net present value: the value of all future cash over the life of an investment discounted to the present.

Nominal/real GDP: Gross domestic product (GDP) is the value of all finished goods and services produced by a country, within a specific time period (usually quarterly or annually). Nominal GDP is GDP given in current prices, without adjustment for inflation. Real GDP is adjusted for inflation.

Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA): A DSA classifies countries based on their assessed debt-carrying capacity, estimates threshold levels for selected debt burden indicators, evaluates baseline projections and stress test scenarios relative to these thresholds, and then combines indicative rules and staff judgment to assign risk ratings of debt distress.

High yield bond: A bond with a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond, also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

The J.P. Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index: This index tracks liquid, US Dollar emerging market fixed- and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities. The index was launched in July 1999 with daily historical index levels dating back to December 1993. Historical to-maturity and to-worst statistics are available from December 1997 and December 2001, respectively.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised. Past performance does not predict future returns.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.