Unconscious uncoupling: The drift of UK inflation

Jenna Barnard, Co-Head of Global Bonds, explores inflation and bond yields and what is causing the UK to be an outlier.

6 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Inflation among developed markets had tended to be synchronous since the initial COVID shock but something odd has emerged in the UK during 2023, which has caused UK inflation to be stubbornly higher and similarly gilt yields.

- Explanations for the inflation conundrum range from benign/temporary reasons through to potentially more persistent inflation.

- For international investors, there are potentially easier markets in which to invest, where the inflation outlook offers an earlier return to normality and the potential for rate cuts.

The experience of inflation among developed markets tended to be synchronous since the initial COVID shock but something odd has emerged in the UK during 2023.

Nearly all developed markets experienced a period of low inflation following the 2007-9 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). This came to a rude halt as a combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus to counter the economic effects of COVID lockdowns melded with the supply shocks caused by the war in Ukraine in 2022. Inflation rates of 9-11% – levels not seen since the 1980s – made headlines. While inflation peaked and has come down rapidly in recent months across both emerging and developed markets, in the UK it has proved much more stubborn. Specifically, core inflation has continued to rise in recent months causing a profound crisis of confidence in UK monetary policy.

A regime shift

In the decades before the GFC, UK gilts had typically yielded more than US government bonds and German government bonds. Post the Brexit vote, gilt yields tended to be lower, sitting midway between US government bond yields and German government bond yields. In 2023, they have decisively broken out of this regime and returned to being the highest yielding of the three countries.

Various factors might explain this. Among them are the UK’s large fiscal deficit and its composition (the UK government needs to issue a lot of gilts and has a relatively high number of index-linked gilts that have to pay out more when inflation is higher). Faded appetite from buyers for gilts after recent political upheavals has also not helped. But most important in 2023 is the inflation outlook. The conundrum is why should core inflation have continued to rise at alarming rates in the UK?

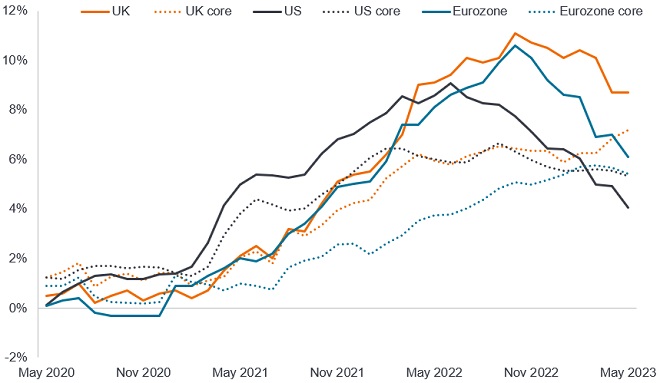

Fig 1: Inflation rates across the UK, the US and the Eurozone

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Consumer Price Index, year-on-year % change, headline inflation in bold lines, core in dotted lines, 31 May 2020 to 31 May 2023. Core inflation excludes energy and food in the US and additionally alcohol and tobacco in the UK and the Eurozone.

Core inflation (which excludes the volatile items of food and energy) typically lags headline inflation. In the US, it is likely to come down further as we know what wholesale used car prices and market rents are doing and these feed into official inflation statistics with a lag. In the UK bizarrely, it is not just services but core goods prices have started reaccelerating and core inflation is still ticking up as a result.

There are a number of ways to try and explain the UK inflation conundrum ranging from benign/ temporary explanations to one of a much more problematic persistent inflation problem.

Be patient

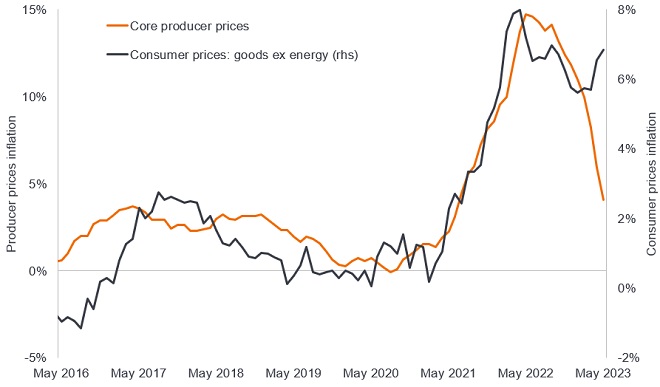

The first is it may be down to time lags and measurement quirks so no need to panic. If we look at producer price indices, these are coming down swiftly and are likely to follow through into consumer prices (although recent profit margin expansion and pass through of exchange rate costs disrupted the downward trajectory). The energy price cap drops are likely to feed into drops in the July data when it is released in August. Monthly core inflation prints are subject to huge overshoots/undershoots in either direction and it will take time to assess the true trend.

Fig 2: Core consumer goods inflation curiously ticked up as producer prices moderate

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, UK Producer Price Index: output prices ex food, beverages, tobacco and petroleum; UK Consumer Price Index: non-energy goods, year-on-year % change, 31 May 2016 to 31 May 2023.

UK inflation has been brought forward

The second is the notion that inflation was sucked into the first half of this year. Firms that set prices in response to events are referred to as “state dependent” whilst those that change prices at regular fixed intervals e.g. annually are described as “time dependent”. The Bank of England’s Decision Maker Panel (DMP) Survey of firms noted that state dependent price setting firms have been raising prices more than time dependent firms. Companies may have pushed through prices while they could in the expectation inflation would be softer later in the year. Encouragingly, when asked about price rises for next year, state dependent firms (which make up about 60% of firms) predicted lower inflation than time dependent price setters.

A persistent inflation problem

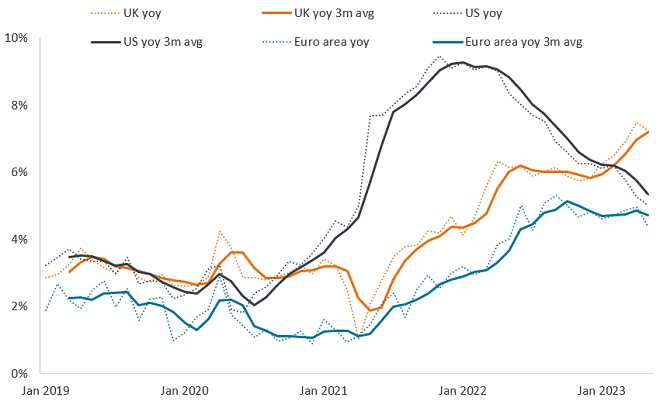

The third is that the UK has become unhinged from the US and Europe and has more persistent inflation. Reasons might be due to greater trade friction post Brexit leading to higher costs and a peculiarly tight labour market. While wages in the US and Europe are moderating, this is not yet evident in the UK.

Fig 3: Wage growth in UK is still accelerating while moderating elsewhere

Source: Indeed Wage Tracker, January 2019 to May 2023. Yoy = year-on-year % change. The euro area series is an employment-weighted average of France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, and Spain. The 3-month average compares a 3-month period with the same 3-month period a year ago to smooth out distortions in an individual month.

Such profound uncertainty sourced from a lack of true understanding about what is driving UK inflation has caused a crisis of confidence on the interest rate outlook. UK peak rate expectations surged higher in early July on little/no meaningful economic data, reaching over 6.5%.1 A sudden concern that interest rates may be having little impact on the UK economy created this airpocket in rate expectations. This argument ignores lags inherent in monetary policy but reveals the crisis of confidence surrounding UK monetary policy at present. Last October, the crisis of confidence was of course about fiscal policy.

Overseas preference

Given the uncertainty surrounding the drivers of UK core inflation for most international investors there are much easier bond markets in which to invest. This includes economies where the inflation story is showing the potential for a return to normality, albeit for core inflation this will still take some time as it typically lags. In emerging markets there are already nascent debates about the first rate cuts, while for most central banks in the developed world the debate is about the last rate hike or two in this cycle. Sitting in the UK, the global covid inflation shock can look very different to other economies e.g. China where CPI inflation has hit 0% in June 2023 or the US down to 3% (from 9.1% a year ago).2

1Source: Bloomberg, interest rate projections, correct at 6 July 2023.

2Source: Refinitiv Datastream, China CPI inflation, US CPI inflation for June 2023, as at 12 July 2023.

Gilts: Government bonds issued by the UK government to finance UK national debt. Index-linked gilts have coupon (interest payments) and final maturity value (amount repaid on the date the bond matures) that are adjusted in line with the inflation rate.

Inflation: The rate at which the prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. Headline inflation refers to inflation across all goods and services, whereas core inflation excludes components that exhibit large amounts of volatility from month to month such as fuel and food prices.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different bonds will be affected differently. In particular, bond prices generally fall when interest rates rise or are expected to rise. This is especially true for bonds with a higher sensitivity to interest rate changes. A material portion of the fund may be invested in such bonds (or bond derivatives), so rising interest rates may have a negative impact on fund returns.