Not so fast: The Fed exercises a circumspect approach

Global Head of Fixed Income Jim Cielinski and Portfolio Manager Daniel Siluk argue that a resilient U.S. economy and decelerating inflation allow the Federal Reserve (Fed) to return the policy rate to a neutral stance without placing either component of its dual mandate at risk.

7 minute read

Key takeaways:

- In reducing expectations for the timing and number of rate cuts, the Fed reminded the market that it remains focused on ensuring inflation returns to its 2.0% target.

- With economic growth proving resilient and inflation decelerating, the Fed has the luxury to slowly return its policy rate to a neutral stance that balances the risks of its dual mandate.

- The broad-based fixed income rally has created opportunities for investors to differentiate between segments that accurately reflect their prospects and those where mispricing may exist.

In the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) January meeting, Chairman Jerome Powell was charged with the task of explaining how to reconcile the U.S. central bank’s December pivot with a still-resilient domestic economy. With the Fed’s decision to keep rates steady never in doubt, the key takeaway from the meeting was bound to be how this messaging would differ from its December statement. And the central bank did indeed affirm that it would need to gain “greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2.0.%” before it could embark on rate reductions. We view this insertion as a reality check for markets that had not only welcomed the Fed’s December pivot but doubled down by predicting up to six 25 basis-point (bps) reductions in 2024.

In forecasting 150 bps of cuts for this year, we don’t think the market fully appreciated the starting point. At 5.5%, the upper bound of the Fed’s target is – at least by recent historical standards – exceptionally restrictive. Such levels were justified given the post-pandemic surge in inflation. Within this context, we did not interpret the Fed’s December statement as overtly dovish, driven by economic data flashing red (they are not). Instead, we viewed the possibility of three cuts in 2024 as an incremental move toward a neutral stance – a tactic afforded by a resilient economy and inflation continuing its downward path.

Balancing the mandate

Absent a crisis, the Fed is an institution that prefers to gauge economic conditions and implement policy methodically. We believe this is precisely what’s in store for 2024. Perhaps the biggest surprise of this cycle is the realization that a 5.5% overnight rate is not as restrictive as many had feared. Economic data bear this out and provide evidence that the U.S. economy is less rate-sensitive than in the past. With job growth buoyant, the Fed maintains optionality in the cadence of its path toward the neutral rate.

Changes in rate sensitivity is not the only factor the Fed must consider when deliberating policy. Just as headline consumer price inflation reaching 9.0% was an extraordinary development brought on by the pandemic and the policy response, so too is the labor market continuing to benefit from idled workers getting lured back to the workplace and goods inflation having receded as supply chains returned to normal. As those disinflationary factors run their course, the baton must be passed to services inflation, which has proven far stickier. In fact, Chairman Powell stated that a chief concern is not inflation reaccelerating, but rather stabilizing at a rate above its 2.0% target.

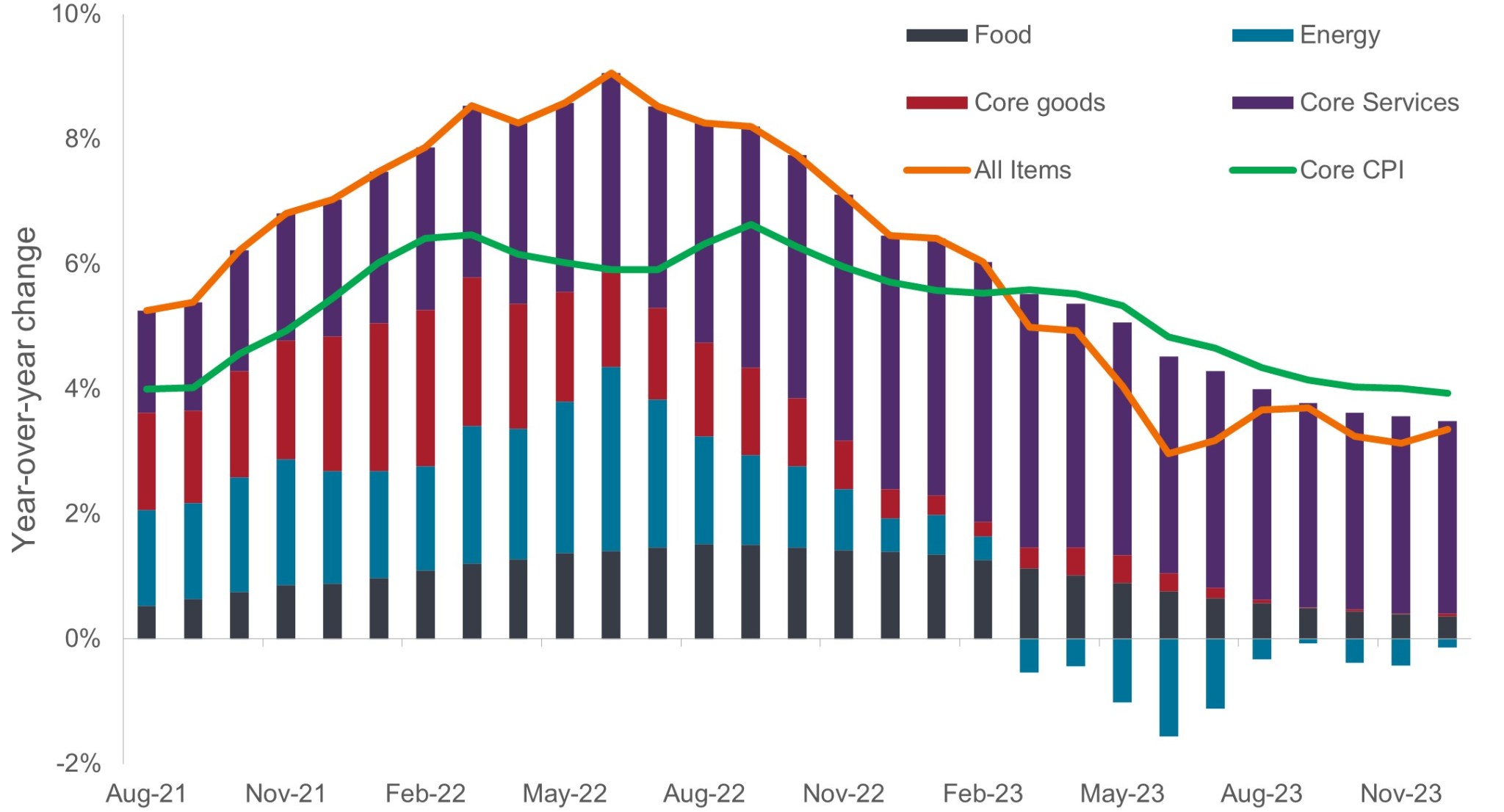

Components of consumer price index

With inflation coming down thanks to lower goods and energy prices, the Fed will want to see services’ contribution to inflation fall further before getting more comfortable with cutting rates.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 31 January 2024.

Forward guidance: Too much of a good thing?

Forward guidance has been a hallmark of the Fed since the Global Financial Crisis. Yet, the objective of transparency can lead to markets quickly pricing in the potential path of policy, forgetting that ongoing economic and market developments get a say as well. Sovereign bonds rallied on the back of the Fed’s December statement, and U.S. equities reached record levels in January. These are two key inputs in financial conditions, meaning that before a single rate cut was executed, conditions eased. Furthermore, low volatility across asset classes has reduced the cost of hedging riskier assets, further contributing to a bull market. With the Fed rightly focused on ensuring inflation doesn’t settle above 2.0%, we believe it will be methodical in lowering the policy rate, accounting for all factors that could ease financial conditions so it does not undo its hard-fought gains against inflation.

What’s priced in?

As we stated in our 2024 Market GPS, bonds are in a better place with respect to providing ballast to a diversified portfolio. Along with preserving capital and registering lower volatility, a bond allocation now also has the potential to generate levels of income not seen in over a decade and provide the capital appreciation that can offset losses in riskier asset classes should those markets sell off.

The resetting of rates since October – and accelerated by the Fed’s December pivot – means that bond investors must be cognizant of which segments of the market more fully reflect current risks and where others may represent opportunity. With the federal funds rate inevitably coming down, the front-end yields on the U.S. Treasuries curve that are more anchored to policy rates already reflect this likely path. Still, on a risk-adjusted basis, shorter-dated maturities remain attractive, in our view. Such positioning also acknowledges the Fed’s concern of inflation settling above 2.0% over the long term, something that could likely weigh on longer-duration Treasuries.

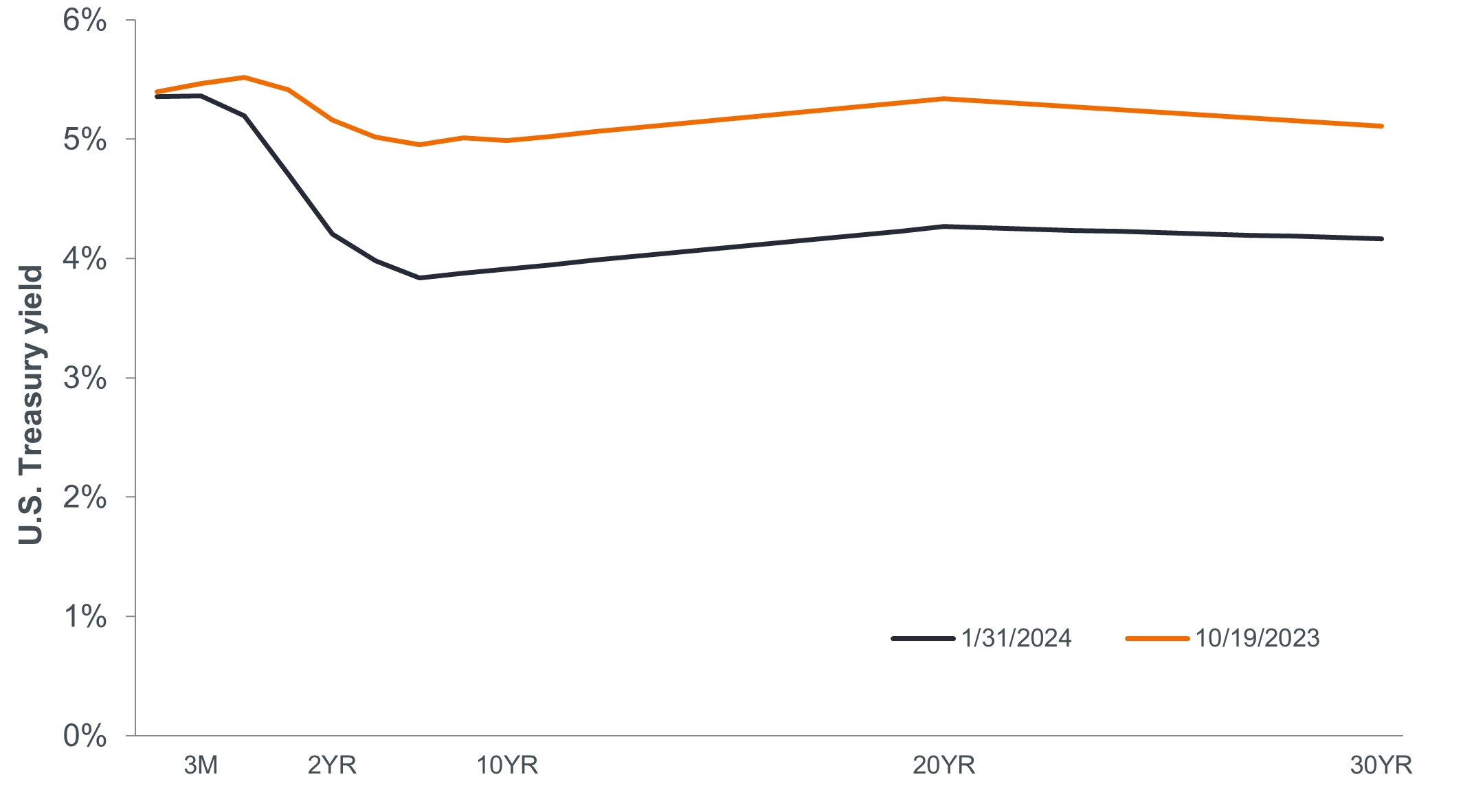

U.S. Treasuries yield curve

The market aggressively price in imminent rate cuts along the front end of the Treasuries curve, while longer-dated maturities have proven slightly more volatile as questions linger about economic growth and the future path of inflation.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 31 January 2024.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 31 January 2024.

Importantly, the breadth of the bond rally belies that global policy – and thus economies – are moving in lock step; they are not. In fact, some regions, among them the eurozone and New Zealand, may need to see policy rates come down further than what’s priced in to stave off a material recession, while others (e.g., Australia) may have to hold steady for longer given elevated inflation.

Actively managing bond exposure also matters with respect to types of securities. Securitized credits seem to have priced in greater potential for a softer-than-expected economy; lower-quality corporate credits, not so much. Even if only a soft landing materializes, quality is important. We maintain the view that the investment-grade issuers that were able to take advantage of low rates to extend maturities offer better value now than high-yield issuers with cyclical exposure whose credit ratings did not enable them to lock in low rates.

Just like the Fed, proceed with caution

The Fed is not going to be bullied by the markets. The conditions for easing are present, and we believe that both policy rates and longer-term rates will indeed decline in 2024.

The key for investors is to avoid getting fixated on whether the first move is in March or May. What is important is that the direction of policy has reversed. Inflection points tend to be good for both bonds and equities, and markets have already moved to price in this friendly policy backdrop. However, asset prices seldom move in a straight line, and the odds of a soft landing have risen. Policymakers are your friend, but a little patience is in order.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Securitized products, such as mortgage- and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed-income securities.

U.S. Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the U.S. Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and U.S. Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market.

A yield curve plots the yields (interest rate) of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. Typically bonds with longer maturities have higher yields.