Monetary policy divergence

For bond markets in 2025 the synchronous global inflation shock of 2021-22 will be receding even further into the distance whilst the divergent effects of US tariff threats will likely be at the forefront of investors’ minds.

The former (inflation and its subsequent retreat) was always going to generate a greater degree of monetary policy divergence across central banks and has indeed been reflected through individual country performance in 2024. It is worth reflecting that the experience of central banks cutting and hiking almost in unison in the years 2020-22 was a historical aberration and more differentiation is something of a return to normality.

The latter (US tariffs), if large enough in scale, has the potential to cause a profound new macro shock i.e. to catalyse disinflation and a negative growth impulse outside of the US versus an inflation shock within the US. At the time of writing, the threat of across-the-board global tariffs is not the base case in any of the outlooks from investment banks nor reflected in the pricing of bond markets. All have assumed relatively modest tariffs outside of China, i.e. that President Trump is more concerned with using tariffs as a stick to drive transactional agreements and hence result in muted tariff outcomes following negotiation. In contrast, the President’s actual statements on tariffs, going all the way back to the 1980s, reflect a deeper-held belief. That the global trading system has been detrimental to the US and needs fundamental realignment via meaningful across-the-board tariffs, with a particular focus on a strategic decoupling from China. Which approach President Trump chooses to take, for which countries, will be critical for individual bond markets in 2025.

Fiscal winds shifting

The 2020 US election coincided with the publication of Stephanie Kelton’s book “The Deficit Myth” and central bank concerns about a structural undershooting of inflation targets over the preceding decade. The 2024 election sees the exact opposite backdrop: too high consumer prices as a dominant popular concern and a hunt for cost savings to fund existing tax policies.

In the Eurozone, another year of negative fiscal impulse has been proposed in budgets submitted to the European Commission (approx. -0.4% for 2025 versus -1.0% in 2024)1. In China, there is some hope of genuine stimulus in 2025 as the recent US$1.4trillion2 swap of local government for federal government debt was a disappointment to many expecting proactive growth enhancing measures.

Meanwhile, in the US, Trump’s fiscal plans centre around an extension of existing tax policy, which is not a new fiscal impulse for growth and inflation but rather the status quo. The tightest percentage majority in the House of Representatives since the 1917-19 Congress acts as a severe constraint to additional tax cuts without offsetting cost cuts. No doubt, governments continue to labour under enormous debt loads, which can serve to crowd out the private sector (the UK is a great example of this) but the marginal newsflow is quiet on the fiscal front.

Interest rate reference points

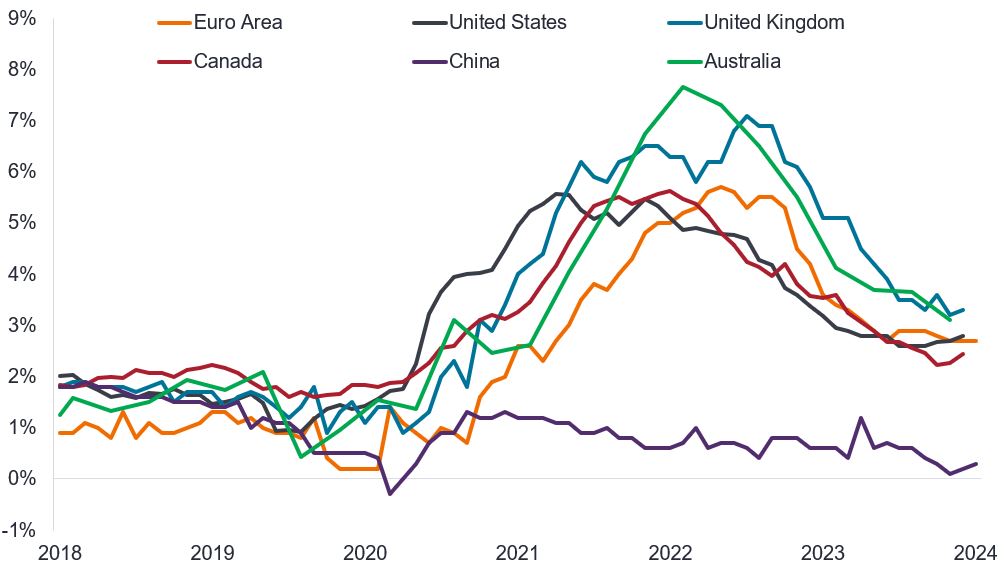

This leads us to a recap of the underlying yardsticks by which bond investors will make their judgements on likely interest rate moves and forward bond returns. These continue to be driven by two key economic statistics. The first is core inflation, with a particular focus on what central banks judge as the best measure of domestically driven inflation i.e. core services inflation. This measure will always lag the decline in headline inflation that has been seen across the world (driven by weak commodity prices and year-on-year base effects) but some countries have made far better progress than others. The chart below highlights the progress made in different countries.

Figure 1: Core inflation is in retreat (year-on-year % change)

Source: Bloomberg, core inflation year-on-year % change. Euro Area Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices, US Core Personal Consumption Expenditure Index, UK Core Consumer Prices Index, Canada Core inflation, China core inflation, Australia Core Consumer Prices Index. 30 November 2018 to 30 November 2024.

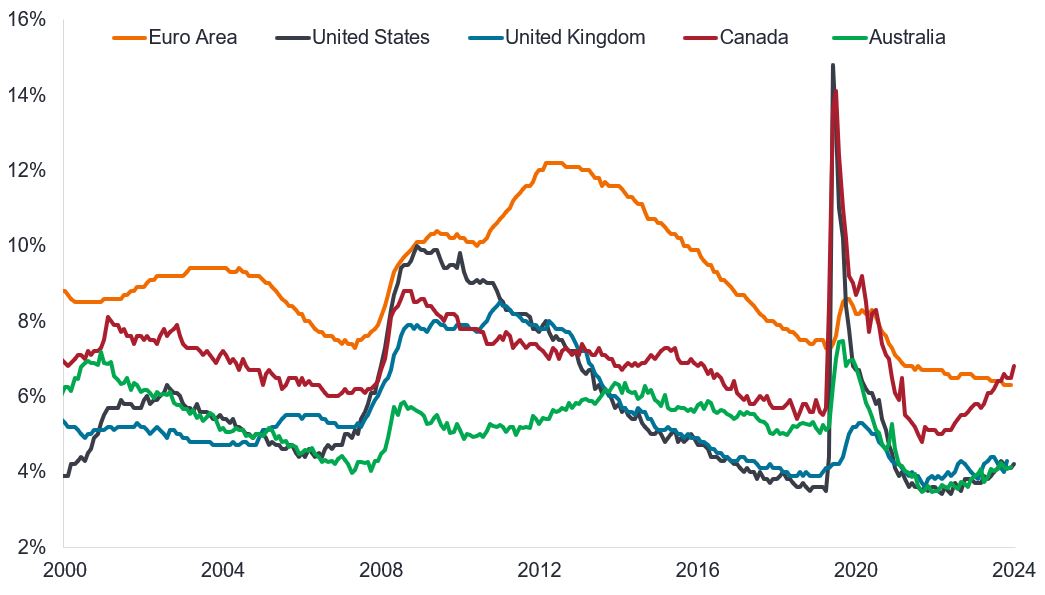

The second statistic to which bond markets are always highly attuned is unemployment. Again, the heady days of the post pandemic hiring binge (2021-22) are long gone and a degree of slack or softening (which is verging on worrying) is a common feature across the developed world. In Canada, the rise in unemployment from 4.8% to 6.8%3 has already driven one of the most aggressive interest rate cutting cycles in 2024 with 175 basis points (bp) of rate cuts in just over six months. In contrast the US and the Eurozone have cut by 100bps versus the UK by 50bps.4

Figure 2: Unemployment rates are on the rise

Source: Bloomberg, unemployment rates, 30 November 2000 to 30 November 2024.

In summary, bond markets are priced for moderate interest rate cuts as central banks take their time getting rates back to what they deem neutral territory amidst expected soft landings across the developed world. In contrast, the political world is braced for the upheaval and chaos of Trump’s second term. Should the latter come to pass, bond returns in a number of countries could end up being positively exciting for investors.

1Source: Janus Henderson, aggregate of broker views from Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Citi, BofA, Morgan Stanley and European Commission, October 2024

2Source: China Standing Committee of National People’s Congress, announced on 8 November 2024.

3Source: Bloomberg, Canada unemployment rate, announced on 8 November 2024.

4Source: LSEG Datastream, 4 June to 19 December 2024, Bank of Canada policy rate, Federal Reserve target rate, European Central Bank deposit rate, Bank of England Bank Rate.

Basis points: Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%, 100bps =1%.

Crowd out: An economic theory that rising government spending drives down or eliminates private sector spending.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Disinflation: A fall in the rate of inflation.

Fiscal impulse: The change in the government primary deficit (which excludes net interest payments) from one year to the next. A positive fiscal impulse is stimulatory for the economy, while a negative fiscal impulse is contractionary.

Fiscal policy: Describes government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy. The Consumer Price Index is a measure of inflation that examines the price change of a basket of consumer goods and services over time. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index is a measure of prices that people living in the US pay for goods and services. Core Inflation are price indices that exclude volatile items, typically food and energy.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Neutral rate territory: A level of interest rates that is neither expansionary nor contractionary for the economy, i.e. where the economy is in equilibrium (full employment and stable inflation)

Strategic decoupling: A deliberate strategy to lessen the reliance on another country, typically manifested through a rebalancing of trade and greater self-sufficiency.

Tariff: A tax or duty imposed by the government of one country on the import of goods from another country.

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.