High yield bonds outlook: Taking the scenic route in 2025

Brent Olson and Thomas Ross, fixed income portfolio managers, believe that high yield bonds offer comfortable driving for now, but investors might need to negotiate more difficult terrain later in 2025.

8 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Tight credit spreads reflect strong fundamentals and ongoing support from investors seeking assets with higher yields – spreads may stay tight for some time.

- The negative aspects of tariffs affecting trade and earnings need to be weighed against possible benefits from tax cuts, deregulation and support from central banks cutting rates, which could just as easily stoke animal spirits among corporates.

- Towards the back end of 2025, we anticipate event-induced volatility will generate distinct winners and losers and offer opportunities on which active management can capitalise.

High yield bonds motored along in 2024, benefiting from both their high income and a boost from credit spreads (the additional yield that a corporate bond pays over a government bond of similar maturity) tightening (moving lower), which had the effect of generating capital gains as it pulled yields lower. Recall that bond prices rise when yields fall and vice versa. We think 2025 should shape up to be another positive year for high yield, albeit with returns more likely to be driven by income as spread tightening fades and gives way to some widening.

With credit spreads towards the tight (lower) end of their range, it is becoming difficult for them to tighten much further. Yields on high yields bonds are, however, close to the middle of where they have been trading over the past 20 years.1 With central banks likely to pursue further interest rate cuts in 2025, we think investors will continue to see attractions in high yield bonds given average yields of 5.6% in Europe and 7.2% in the US.2

There is some tension in the markets as we await the new Donald Trump administration and how quickly and to what extent policies are enacted. A difference to 2016 when Trump last became US president is that many high yield bonds are trading below par value: on average 96 cents in the dollar.3 Much of this is a legacy effect from bonds being issued with coupons (interest rates) below today’s yields a few years ago. It does, however, offer a useful pull to par as the bond price rises as it gets closer to maturity (when the par value is repaid).

Sticky spreads

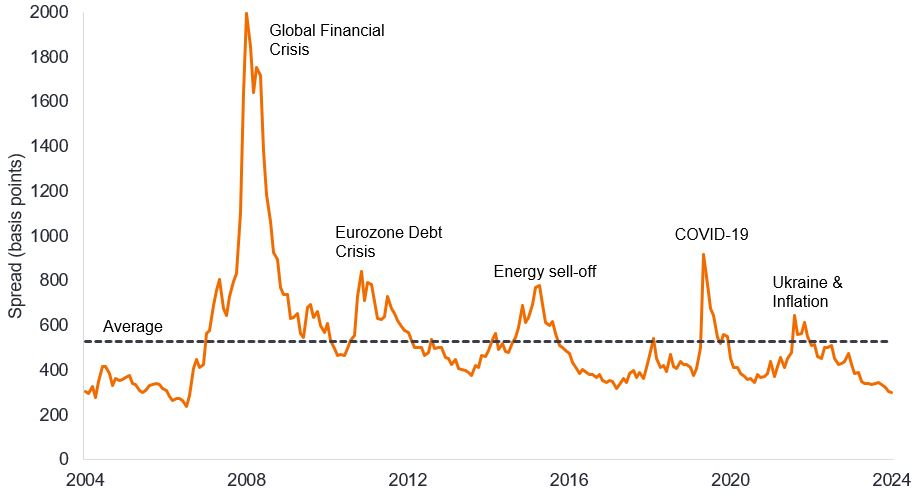

Spreads are tight but it is not unusual for them to stay tight for long periods, as Figure 1 shows. This is because corporate conditions take time to change. Once they have been through a period of change they tend to settle at the extreme, i.e. spreads spike higher during a crisis and take some time to retreat while staying low during a period of economic stability.

Figure 1: Spreads can stay tight for extended periods outside crises

Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA Global High Yield Index, Govt option-adjusted spread in basis points., 30 November 2004 to 30 November 2024. Average is average spread over the past 20 years to 30 November 2024. Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%. Past performance does not predict future returns.

Shocks may come from the Trump administration, but the real impact is likely to be felt later in 2025 as it takes time to legislate changes to government spending or taxation. Tax cuts and deregulation could improve profits in selected areas but these gains need to be offset against the (potentially bad) impact of tariffs and any government department spending cuts. Tariffs might be enacted more quickly; the level and extent of retaliation will be important factors in how this affects corporate profits. Furthermore, some of the mooted policies may be counterproductive; for example, relaxing regulations on oil and gas drilling could lead to lower earnings among some energy companies if higher volumes are offset by lower energy prices.

Spreads are often a barometer of sentiment. We think the positive sentiment towards equities and credit markets can persist in the near term, keeping spreads low. But it may prove trickier in the second half of 2025 for three reasons. One, we think the US Federal Reserve (Fed) may have paused rate cuts by then, removing a tailwind; two, steeper rate cuts in Europe are likely to pull down government bond yields but this may cause spreads in Europe to adjust wider to prevent yields on high yield bonds getting too low; three, equity markets are likely to face a correction at some point and high yield spreads often widen when equity markets weaken.

Technicals remain good

High yield bonds were not short of buyers in 2024 despite a notable rise in supply, and we think this can continue through most of 2025. Better quality high yield, we believe, should still generate investor appetite as declining interest rates encourage a search for yield. An irony of yields and coupons (interest payments to investors) being higher than they were a few years ago is that this can generate additional demand for bonds. This is because many investors choose to reinvest the income. The make-up of the buyer base for high yield bonds has also improved as there is more institutional ownership from insurance companies and total return fixed income funds.4

There is a risk that companies bring forward issuance to the first half of 2025 to try and get ahead of any fallout from tariffs. Similarly, the prospect that the Fed may not cut rates as much as hoped for by the markets could also lead more indebted borrowers scrambling to secure finance. We think dispersion will become more evident as the year progresses as more distressed borrowers get separated from the stronger.

Yet in the main, high yield companies have not been reckless with their borrowing. Most of the proceeds from bond issues have been used to refinance existing debt rather than engage in typically less bond-friendly activities such as merger and acquisition activity (M&A) or to fund dividends or share buybacks. Leveraged buy-outs (LBOs) at the moment are restricted by the fact that the equity market is very strong so price to earnings multiples are high – buyers are wary of overpaying.

Figure 2: Use of proceeds from USD high yield bond issuance

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, S&P, LCD. Calendar years 2012 to 2023. Year to date (YTD) to 31 October for 2024.

Trump’s pro-growth agenda – and a faster pace of interest rate cuts in Europe – could drive animal spirits among corporates and lead to a pick-up in M&A, as might deregulation. This could lead to more bond issuance. In one respect this might be seen as negative because more supply needs to be met by more demand. Yet M&A might be a positive for those high yield companies that are takeover targets. This is especially true for more stressed (higher spread) names where the credit rating may improve if acquired by a stronger entity.

Under the hood – fundamentals good for now

Default rates have remained modest – in fact, the US 12-month trailing default rate dropped to a 29-month low of just 1.14% at the end of November 20245 – and stressed areas of the market have been well telegraphed. We take comfort from the fact that leverage levels (debt/earnings) are at or below average levels for the last 20 years in the US and Europe. The higher interest rates today compared to a few years ago mean interest cover (earnings/ interest expense) has fallen from recent highs but is simply back to average levels.6

Risks to corporate fundamentals are external (tariffs causing some loss of revenue and lower earnings) or internal (companies choosing to borrow more, for some of the reasons illustrated in Figure 2). We expect some modest deterioration as the year progresses.

Changing scenery – regional differences

A notable feature of 2024 was that rate cut expectations kept changing. This created opportunities to tilt portfolios regionally depending on expectations for economic growth and bond yield direction. 2025 is likely to involve a continuation of that dynamic approach.

While trying to second-guess Trump’s intentions may be a fool’s game, we need to take his desire for tariffs at face value. Some of the more extreme proposals are likely to be a negotiating tactic rather than the eventual outcome. While it is consensual to think that Trump’s agenda is likely to see the US economy outperform and tariffs to be a drag on Europe’s economy, we think there may be some useful offsets. Monetary policy is likely to have to work harder, with the European Central Bank cutting rates faster. Provided revenues at high yield companies do not collapse, this could even help alleviate refinancing concerns among some of the more indebted borrowers. Politically, Trump’s presidency may also hasten a resolution of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, relieving a worrying overhang for Europe. Similarly, elections in Germany could lead to structural reforms that permit a more pro-growth agenda.

One thing is clear. With a less predictable president entering the White House, markets will be less sure about what is round the corner. Greater uncertainty warrants a careful driver.

1Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index, yield to worst, 20 years to 31 October 2024.

2Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US High Yield Index, ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index, yield to worst, at 30 November 2024. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

3Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA Global High Yield Index, par weighted price (value out of a par value of 100) at 30 November 2024.

4Source: BofA Global Research, 29 October 2024.

5Source: JPMorgan Default Monitor, par-weighted default rate for the 12 months to 30 November 2024, 2 December 2024.

6Source: Morgan Stanley, Q2 2024 net leverage and interest cover ratios, as at 1 November 2024.

Animal spirits: A term coined by economist John Maynard Keynes to refer to the emotional factors that influence human behaviour, and the impact that this can have on markets and the economy. Often used to describe confidence or exuberance.

Basis points: Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%.

Call: A callable bond is a bond that can be redeemed (called) early by the issuer prior to the maturity date.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Corporate fundamentals are the underlying factors that contribute to the price of an investment. For a company, this can include the level of debt (leverage) in the company, its ability to generate cash and its ability to service that debt.

Coupon: A regular interest payment that is paid on a bond, described as a percentage of the face value of an investment. For example, if a bond has a face value of $100 and a 5% annual coupon, the bond will pay $5 a year in interest.

Credit rating: A score given by a credit rating agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s and Fitch on the creditworthiness of a borrower. For example, S&P ranks investment grade bonds from the highest AAA down to BBB and high yields bonds from BB through B down to CCC in terms of declining quality and greater risk, i.e. CCC rated borrowers carry a greater risk of default.

Credit spread is the difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Federal Reserve (Fed): The central bank of the US which determines its monetary policy.

High yield bond: Also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index tracks EUR denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the euro domestic of eurobond markets.

ICE BofA Global High Yield Index tracks USD, CAD, GBP and EUR denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the major domestic or eurobond markets.

ICE BofA US High Yield Index tracks US dollar denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy. The Consumer Price Index is a measure of inflation that examines the price change of a basket of consumer goods and services over time. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index is a measure of prices that people living in the US pay for goods and services.

Interest coverage ratio: This is a measure of a company’s ability to cover its debt payments. It can be calculated by dividing earnings (before interest and taxes) by the interest expense on a company’s outstanding debt.

Investment grade bond: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments, reflected in the higher rating given to them by credit ratings agencies.

Issuance: The act of making bonds available to investors by the borrowing (issuing) company, typically through a sale of bonds to the public or financial institutions.

Leverage: The level of borrowing at a company. Leverage is an interchangeable term for gearing: the ratio of a company’s loan capital (debt) to the value of its ordinary shares (equity); it can also be expressed in other ways such as net debt as a multiple of earnings, typically net debt/EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation). Higher leverage equates to higher debt levels.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Par value: The original value of a security, such as a bond, when it is first issued. Bonds are usually redeemed at par value when they mature.

Refinancing: The process of revising and replacing the terms of an existing borrowing agreement, including replacing debt with new borrowing before or at the time of the debt maturity.

Tariff: A tax or duty imposed by the government of one country on the import of goods from another country.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Yield to worst: The lowest yield a bond (index) can achieve provided the issuer(s) does not default; it takes into account special features such as call options (that give issuers the right to call back, or redeem, a bond at a specified date).

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

Specific risks

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- In addition to income, this share class may distribute realised and unrealised capital gains and original capital invested. Fees, charges and expenses are also deducted from capital. Both factors may result in capital erosion and reduced potential for capital growth. Investors should also note that distributions of this nature may be treated (and taxable) as income depending on local tax legislation.